Democrats are worried. But will RFK Jr take more votes away from Trump?

-

Published

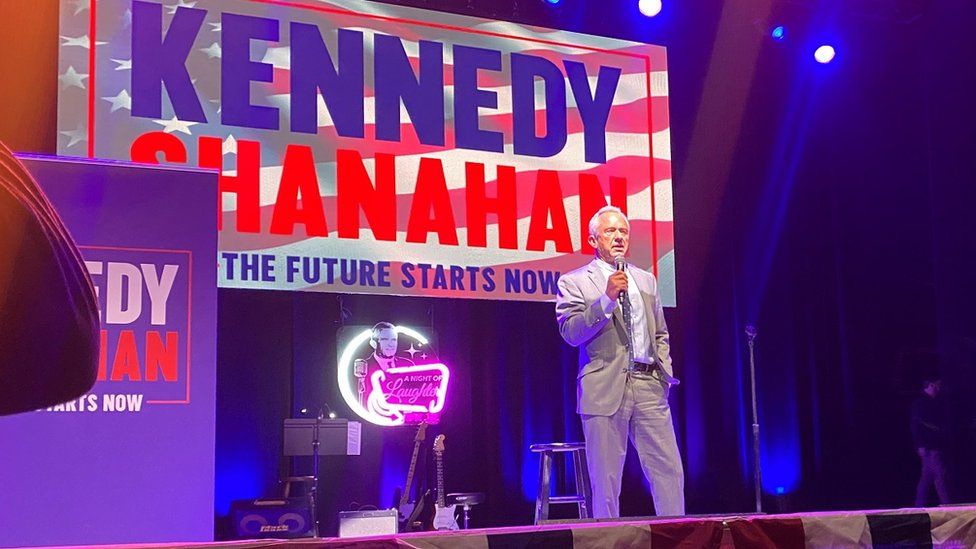

Mike Panza showed up early to a comedy benefit to support the Kennedy campaign for president.

Wearing a Star Wars-themed shirt and queuing outside the Royal Oak Theatre in this Detroit suburb, he talked about what drew him to the one candidate in the 2024 race identifiable solely by his initials – RFK Jr.

“I’d like a return to the middle of the road,” said Mr Panza, 44. “His stance on health care is really appealing. Kennedy wants to make people healthy, he wants to make the country healthy.”

Mr Panza, who works as an environmental officer, might sound like a disaffected Democrat. But when I ask who he voted for in 2020, he answers immediately: “Trump.”

Interviews with dozens of Robert F Kennedy Jr supporters here point to a paradox about the independent candidate, one of the biggest wildcards in November’s presidential election.

Conventional wisdom, backed up by some opinion polls, says that Mr Kennedy, a member of the country’s most famous – and Democratic – political family, presents more of a threat to Joe Biden than to the Republican nominee Donald Trump.

However, other recent surveys, interviews with supporters and a closer look at the issues that animate Mr Kennedy’s base tell a different story – that perhaps Mr Trump is the candidate who should be more worried.

“Given the status of politics in Michigan right now, I would say he’s probably more damaging to Trump,” said Corwin Smidt, a politics professor at Michigan State University. “But it’s a very uncertain situation.”

Mr Kennedy is consistently polling in the teens or high single digits, percentage-wise. By all indications he is the most popular independent or third-party candidate in decades.

Experts say support for third-party candidates tends to decline closer to the election, and that Mr Kennedy is extremely unlikely to win the White House. Yet, because of the tight electoral map, his significant support has the potential to influence results in some states – including Michigan, a key battleground – and ultimately determine who becomes the next president.

Just a few miles away from the comedy show, local Republicans in suburban Macomb County hold a pro-Trump rally every Sunday at a wide intersection surrounded by strip malls, fast-food outlets and a gas station.

This is hotly contested territory. Mr Trump carried around 53 percent of voters in Macomb, in both 2016 and 2020.

But in the last election, the share of the vote going to third-party candidates declined, allowing Joe Biden to improve on Hillary Clinton’s slice of the vote by about 3.5 percentage points. It was one small piece that allowed Biden to flip Michigan back into the Democratic column in 2020.

At the gathering of a couple of dozen Republicans waving American flags and handmade pro-Trump signs, reaction to the Kennedy campaign ranged from guffawing bemusement to mild approval.

Peter Kiszczyc is a regular at these rallies. He says he’s glad that independent candidates such as Mr Kennedy Jr and left-winger Cornel West have entered the race.

“Some leftists will vote for them,” said Mr Kiszczyc, 69, who emigrated to Michigan from Poland in the 1980s. “Some things I like about RFK, some I don’t.”

But he was in deep agreement with one of Mr Kennedy Jr’s most noteworthy – and controversial – issues. “All of us support his position against vaccination,” he said, gesturing at the small crowd of Trump fans.

After a career as an environmental lawyer, Mr Kennedy headed the anti-vaccine organisation Children’s Health Defense. Its support and fundraising skyrocketed – as did Mr Kennedy’s profile – during the Covid-19 pandemic.

His activism has put Mr Kennedy on the opposite side to most Democrats of a cultural and political divide that formed during the pandemic – and which was particularly acute in Michigan.

In April 2020, then-President Trump focused his ire on Gretchen Whitmer, the state’s Democratic governor, for imposing lockdown measures, tweeting: “LIBERATE MICHIGAN!” The state was the site of numerous protests against Ms Whitmer’s Covid policies, including tense armed rallies at the state capitol.

“A lot of the anti-Whitmer voters went for Trump in 2020,” said Mr Smidt, the Michigan State professor.

He noted that many Michiganders drawn towards Mr Kennedy’s position on healthcare and vaccines tend to lean conservative – and thus would more naturally fall into Mr Trump’s camp.

“Democrats in Michigan are not like Democrats in California,” he said.

A number of Kennedy supporters back at the theatre – who paid $99 each for a comedy ticket – declared that they were opposed to lockdowns, masks, and Covid vaccines.

“I think the whole pandemic was mismanaged,” said Sara White, a 43-year-old mother who said she opposed school closings and vaccine mandates. Ms White described herself as a former Democrat – “I voted for Obama,” she said – but noted that in 2020, she cast her ballot for Mr Trump.

The evening began with a short campaign video made by the creator of Plandemic, a series of conspiratorial documentaries about Covid.

The jokes skewed towards issues on the Make America Great Again agenda, including poking fun at gender terminology, “woke” young people and National Public Radio.

After the comedy, Mr Kennedy remarked: “There are people outside tonight who worry that I’m going to take votes away from President Biden and get President Trump elected.

“And there are people who I run into every day who are worried that I’m going to take votes away from President Trump and get President Biden elected. And both of them think that’s going to be the end of our republic… I think our democracy is stronger than that.”

Mr Kennedy’s “pox on both your houses” message resonates with Liz Glass, a 59-year-old self-described recovering Democrat who owns a deli in Boyne City, in northwest Michigan. She voted for Mr Biden in 2020, but won’t again.

“I’m disgusted,” she said in a phone interview. “It seems like the two major parties just want you to hate the other one, more than they have anything to offer that’s positive.”

But Mr Kennedy looks unlikely to be able to take advantage of one the biggest issues for disaffected Democrats, including Michigan’s sizable Arab-American population – the continuing war in Gaza. A staunch ally of Israel, he has rejected calls for a ceasefire.

The two main candidates are – for obvious reasons – attempting to paint Mr Kennedy as a natural ally of the opposite side.

Mr Trump has offered various opinions on RFK Jr, calling him “Crooked Joe Biden’s Political Opponent, not mine” on his Truth Social account – but more recently calling him “a Democrat ‘Plant'”.

The interactions between the two have been even more complicated than that. Although Mr Kennedy is a frequent critic of Mr Trump, he claims that he was approached by allies to see if he would be interested in being Mr Trump’s running mate. The Trump campaign has vigorously denied the claim.

Brian Hughes, a senior Trump adviser, called Mr Kennedy an “ultra-leftist”.

“Despite the dreams of the liberal echo chamber, Kennedy is an existential threat to Joe Biden not President Trump,” Mr Hughes said in a statement, citing Mr Kennedy’s views on taxes, fossil fuels and gun control.

However, a recent NBC News survey indicated that 15% of Trump supporters would switch their votes to Mr Kennedy when presented with his name as an option – as compared to 7% of Biden voters.

That’s a break from several previous polls which showed Mr Kennedy pulling more support away from Mr Biden.

Democrats are still worried about that possibility. Local Democratic activists protesting outside the fundraiser called him a “spoiler”. And Democrats have mounted legal challenges to Kennedy’s efforts to get on the ballot. In Michigan those have come to naught, as Kennedy recently gained ballot access after being nominated by the tiny Natural Law Party.

In a statement to the BBC, Michigan Democratic Party Chair Lavora Barnes took aim at the Kennedy campaign. “The choice is clear this November, we must re-elect President Biden, and there are simply no alternatives,” she said.

At this point in the campaign the overall effect of Kennedy’s bid is unknowable, said Merrill Matthews, a resident scholar with the conservative Institute for Policy Innovation who has studied the history of third-party campaigns.

But, Mr Matthews said, his presence in the race could cause a number of surprises, not only in close battlegrounds like Michigan but states which seem relatively safe for either candidate.

“At a level of 8 or 9 percent – roughly where he is at in the polls now – his support could really jumble the outcome in a number of places,” Mr Matthews said.