Barbara Plett-Usher,BBC Africa correspondent, Cape Town

Kyla Herrmannsen/BBC

Kyla Herrmannsen/BBCJameelah’s room was once a morgue; Faldilah’s was a bathroom; Bevil’s – the doctor’s office where he came to collect his diabetes medication.

All of them are squatting in a derelict hospital in the South African city of Cape Town, protesting at what they see as the government’s failure to deliver affordable housing.

The end of apartheid brought political rights and freedoms for all. But on the eve of the country’s seventh democratic election, enduring inequality still divides this country.

And in many cases the housing policies of the governing African National Congress (ANC) has inadvertently reinforced the geography of apartheid, rather than reversed it.

Activists belonging to a movement called Reclaim the City occupied the Woodstock Hospital in the dead of night seven years ago.

The aim was to take over property close to the city centre, says one of the leaders, Bevil Lucas, because access to the jobs and services this offers is key to righting the wrongs of segregation.

“A new form of economic apartheid” has replaced the racist laws that kept black and coloured people (as mixed-race South Africans are known), trapped in poverty in townships at Cape Town’s edges, he tells the BBC.

“The poor and vulnerable have generally been pushed to the periphery of the city.”

They now have the right to move but cannot afford the high rents demanded by property developers in the city centre.

For Jameelah Davids, location was everything.

“My moving in here was because of my son who’s autistic,” she says. “He goes to school around the corner. It was so near for him. Everything is there. And he’s flourished.”

She settled her family in the former office of the hospital morgue.

Kyla Herrmannsen/BBC

Kyla Herrmannsen/BBCAnother tenant, Faldilah Petersen showed me how she has transformed a hospital bathroom into a home, turning the toilet cubicle into a kitchen, and the basin area into a bedroom.

“I was evicted like 10 times in a year,” she tells me.

“But living in this occupation gave me that opportunity to improve my life, and I’m more free to do what I need to and it’s much more nearer to the city as well. It’s like a homecoming.”

The city authorities have come round to agreeing that the site can be developed for residential purposes, but it calls the current tenants illegal occupiers and says they need to leave before the development starts.

The ANC took power 30 years ago with a Freedom Charter that promised housing to a population deprived of secure and comfortable homes by apartheid. Since then, it has built more than three million and granted ownership for free, or for rent at below market rates.

But the lists for government houses are still long – Ms Davids has been waiting for nearly 30 years, Ms Petersen for longer.

And most have been built far from the city centre, where land is cheaper, failing to reverse the spatial planning of apartheid that embedded inequalities.

Nowhere is that more the case than Cape Town, says Nick Budlender, an urban policy researcher, calling it “probably the most segregated urban area anywhere on Earth”.

It was the entry point for colonial settlers and they designed it that way, he says, so reversing it would take deliberate state intervention. But “since the end of apartheid, not a single affordable housing unit has been built in the inner city of Cape Town”.

He is giving me a tour of car parks that store government vehicles, some gathering dust, targeted by activists as available public land that could be transformed into low-income housing.

“Using a piece of land in the centre of the city that suffers from such a severe segregation crisis to store vehicles instead of providing homes… makes no sense from anyone’s perspective,” says Mr Budlender.

There are signs of a new approach. The provincial government, run by the Democratic Alliance (DA) is building a “better living” model on state land close to the city’s jobs and services.

The Conradie Park project also happens to be the site of a former hospital.

The first phase offers a mix of subsidised and market-value options, and the second phase is under construction.

Provincial Infrastructure Minister Tertuis Simmers does acknowledge a backlog of 600,000 people waiting for housing assistance, but says there are “ambitious” plans to deliver 29 similar social housing projects.

But the budgets are small – he is seeking partnership from the private sector – and timelines uncertain.

And housing, often a hot topic in elections, has slipped down the list of political priorities.

The manifesto of the DA, which is the official opposition party at the national level, does not specifically mention it, nor do other parties.

Kyla Herrmannsen/BBC

Kyla Herrmannsen/BBCIn the narrow lanes of Khayelitsha township, hope for the future is in short supply.

Many of those living in the sprawling crush of corrugated iron shacks leave before dawn to commute to the city for work the way their parents and even grandparents did.

It is a journey of about 30km (18 miles), but the mini-bus taxis and trains they use are expensive, unreliable and often unsafe.

Noliyema Tetakome has lived here for most of her 49 years. She gets water from the communal tap at the end of her alley and uses the public latrines.

She spends a quarter of her meagre salary on transport to her job as a gardener. Some of her neighbours pay up to half of theirs. And she does not expect the election to change that.

Ms Tetakome has marked her X on the ballot in every election so far but “it doesn’t makes any difference”, she tells me.

This time “I’m not going to vote”, she says leaning forward in her chair for emphasis, “because I’m tired. Because I voted before, but I didn’t see change. I’m still here!”

The main thing on her mind is the coming winter rains which she expects to flood her shack again.

Kyla Herrmannsen/BBC

Kyla Herrmannsen/BBCDisillusionment with the governing ANC suggests the party of liberation could for the first time lose the absolute majority it has commanded since 1994.

The third-largest party, the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), is challenging what it calls decades of ANC failure by offering a radical “rescue plan” to redistribute the bulk of the wealth still held by a small minority.

A new party, Rise Mzansi, has tapped into Cape Town’s persistent divisions.

“We believe that South Africans should be able to stay closer to where they work,” the national leader Songezo Zibi said recently on a campaign visit, accusing both the DA and ANC of failing to do the kind of spatial planning the fast-growing city needs.

Rise Mzansi is untested but comes without the baggage of misused power that hobbles the ANC, the sweeping corruption that has darkened its decades of rule.

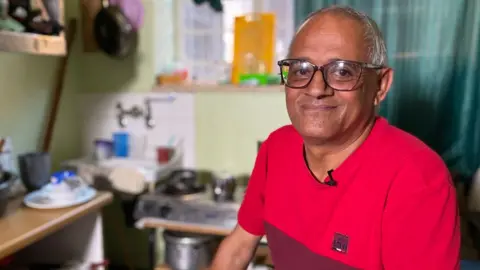

“The powers that be are too closely associated with property power,” says Mr Lucas, talking to me while perched on his bed in cramped living quarters, a room where he used to consult his doctor.

A former anti-apartheid activist who never stopped campaigning for social justice, he says he is disappointed in the outcome of the struggle, but insists the future still has possibilities.

“Because it’s an election, there’s hope, which did not exist under the previous dispensation.”

He still hopes that the political authorities will attend to the scale of social need that remains the legacy of apartheid.

“If it’s not adequately addressed,” Mr Lucas says “it could lead to social unrest, and significant social unrest. Because what do people have to lose when they are already homeless, when they are not able to have shelter?”

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC