Why do we still avoid the number 13?

Sarah Thomas

Sarah ThomasOn the 13th day of a month, the weather turns wet, cold and grey after a gloriously warm and sunny weekend. That’s unlucky.

Coincidence? Of course – this is British weather. But 14% of British people surveyed believe the number 13 is inherently unlucky, while a further 9% don’t know.

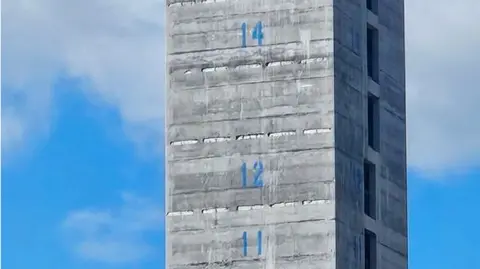

The continuing belief in 13’s malign influence is so baked into our culture that even a down-to-earth profession like building is affected by it, as a construction site in Cardiff has shown.

As some commuters noted, one of the inner supporting towers being built for the Central Quay development on the old Brain’s brewery site had numbers displayed on every floor of the unfinished building – with a glaring omission on the 13th.

This is more common than you might think in the 21st Century. Some buildings, including apartment blocks and hotels, skip 13 entirely.

The 13th floor may be named 12A, or used to house infrastructure the building needs rather than apartments or offices.

Others, like one of the taller hotels in Cardiff, jump straight from 12 to 14.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHouses numbered 13 are usually cheaper while in the past some councils have actually banned new housing developments from using the number because residents do not like living there.

Sarah Thomas from Grangetown in Cardiff spotted the tower on the Brains site when she was coming out of her offices at Network Rail nearby.

“It piqued my curiosity when I saw it was missing,” she said.

“I did assume it was down to superstition, but I Googled to confirm and only then realised how widely practised it is. Quite a few friends have said they’ve been in buildings or lifts where the number 13 is missing – clearly I need to visit some taller structures.”

She describes herself as not superstitious but feels some habits stem from common sense, adding: “I’d rather not walk under a ladder if possible, to avoid the risk of injury.

“I do find the history behind superstitions interesting as they give us an insight into how people connected specific events with more day-to-day activities.”

Some of the most high-profile structures in the UK retain the superstition.

When London’s Canary Wharf was redeveloped and the distinctive One Canada Square tower was built in 1990 – at the time the tallest building in the UK – it opened its doors minus a floor 13 and remains the same today.

And if you want to take a spin on one of the London Eye’s 32 pods, you may be surprised to learn you can book number 33. Which, naturally, replaces the missing number 13.

Why is the number 13 thought to be unlucky?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesConventional wisdom has blamed a number of sources for 13’s supposed bad luck.

One is linked to Christianity – there were 13 people at Jesus Christ’s last supper which happened just before he was betrayed by Judas Iscariot, the 13th to be seated, and arrested for blasphemy.

Similarly in Norse mythology, Loki, the god of mischief and deception, is the 13th guest at a dinner of the gods where he tricks one of Odin’s sons into killing another.

The fear of 13 – officially called triskaidekaphobia – goes into overdrive when coupled with Friday, which is also loosely associated with bad luck because it was the day Christ died on.

Juliette Wood

Juliette WoodBut why do people in supposedly enlightened societies still cling to such a belief?

Perhaps because, surprisingly, it is a pretty modern belief and not one with centuries of tradition behind it after all, according to Cardiff University lecturer Dr Juliette Wood, an expert in mythology and folklore.

“It isn’t folklore in the sense that it’s not an old tradition. It has nothing to do with the fact there were 13 people at the last supper,” she said.

Instead, she believes it is essentially a media creation which became popular around the turn of the 20th Century, which has become a kind of modern folklore in its own right and is reinforced through media, including films such as Friday the 13th.

Marvel/Disney

Marvel/DisneySearches back beyond this time have not produced references to unlucky number 13.

But people look back for stories that fit the creation of a myth, and have latched on to the most famous examples.

“It kind of makes so much sense, particularly because of the last supper link, that it’s stuck,” Dr Wood explains.

The idea of Loki as a source is likely to be even more recent.

She added: “This notion of Norse mythology as a kind of touchstone for culture is actually quite recent.

“It goes back to the interest that you find in Britain in the 19th Century in finding our Germanic heritage and a number of British scholars translated the Nordic myths for the first time.

“And now of course since the Marvel films, Loki is a hero. So you get reasons to focus on a particular figure and you get this kind of transference.”

Unlucky days

The idea of unlucky days is indeed a much older convention – think of the Roman Ides of March (the 15th) which was reinforced in Roman belief following the assassination of Julius Caesar on that day, and popularised by the Shakespearean tragedy telling his story.

Dr Wood said: “We love superstitions. We love to be able to say in this highly mechanistic, highly uncertain world ‘oh well it’s tradition’.

“It seems to go against all sense, but being able to ascribe something to an outside, not malevolent power but certainly fatalistic one, somehow makes us feel more comfortable and less insecure.

Katie Griffin

Katie GriffinKatie Griffin, from estate agent body Propertymark, who runs her own business in Devon, confirms avoidance of the number 13 can still be a thing in housebuilding.

“I wouldn’t say that it would detract from the value [of a house] but sometimes in order to stop that, developers will completely omit number 13. That has been in the past that you will go 11, 12, 14,” she says.

“I don’t specifically have people come in and say ‘I’m superstitious and I don’t want be in number 13’ but they may say ‘I don’t want to be near a churchyard or a cemetery’.

“So when you scratch the surface you suddenly go, oh my gosh there are these things that are out there. It depends whether you are of a sensitive nature, but you could turn it on its head and say well if you buy number 13, you could get a better deal.”

A brief survey of commuters near the tower seemed to suggest most people took the superstition with a pinch of salt (thrown over a shoulder?).

Odessa Barthorpe, from Cardiff, believes superstition is the result of culture or upbringing but would personally happily live on a 13th floor, adding: “I think it’s probably a hangover from days when we didn’t know how the world worked and we had to make stuff up.

“It’s interesting. But in terms of living your life by it, no.”

Carmen Abad from Rhoose, Vale of Glamorgan, grew up in South East Asia where there are “a lot of superstitions” but she doesn’t really believe in them.

“So personally I wouldn’t care about living on the 13th floor. If it was a cheaper apartment I would go for it,” she says

For future residents of the Cardiff tower – the management company has confirmed the 13th floor will have both a number and apartments to rent once it is completed.

Cheaper? Now that would be lucky.