Susannah’s grandad ran Bengal when famine killed millions

BBC

BBC“I feel enormous shame about what happened,” Susannah Herbert tells me.

Her grandfather was the governor of Bengal, in British India, during the run-up and height of the 1943 famine which killed at least three million people.

She is only just learning about his significant role in the catastrophe, and confronting a complex family legacy.

When I first meet her, she is clutching a photograph from 1940. It’s Christmas Day at the governor’s residence in Bengal. It’s formal, with people sitting in rows, in their finery, staring straight into camera.

In the front are the dignitaries – Viceroy Linlithgow, one of the most important colonial figures in India, and her grandfather Sir John Herbert, Bengal’s governor.

At their feet is a little boy, in a white shirt and shorts, knee-high socks and shiny shoes. It’s Susannah’s father.

Susannah Herbert

Susannah HerbertHe had told her some stories of growing up in India, like the day Father Christmas came in on an elephant, but not much more.

But little was spoken of her grandfather, who died in late 1943.

The causes of the famine are many and complex. While John Herbert was the most important colonial figure in Bengal, he was part of a wider colonial structure. He reported to his bosses in Delhi, who reported to theirs in London.

Dr Janam Mukherjee, historian and the author of Hungry Bengal, tells me Herbert “was the colonial official most directly linked to the famine because he was the chief executive of the province of Bengal at that time”.

One of the policies he executed during World War Two was known as “denial”, where boats and rice – the staple food – were confiscated or destroyed in thousands of villages. It was done because of the fear of a Japanese invasion and the aim was to deny the enemy local resources to fuel their advance into India.

However, the colonial policy was catastrophic for the already fragile local economy. Fishermen couldn’t go to sea, farmers weren’t able to go upstream to their plots, and artisans were unable to get their goods to market. Critically, rice could not be moved around.

Herbert family

Herbert familyInflation was already high, as the colonial government in Delhi was printing money to pay for the vast war effort on the Asian front. The hundreds of thousands of Allied soldiers in Kolkata – then Calcutta – were straining food resources.

Rice imports to Bengal from Burma had halted after it fell to the Japanese. Rice was hoarded, often for profit. And a deadly cyclone hit, wiping out much of Bengal’s rice crop.

Repeated demands – in the middle of the war – to the war cabinet and Prime Minister Winston Churchill for food imports were denied or partially heeded at the time.

The numbers who died are overwhelming. I wondered why Susannah, the granddaughter of Bengal’s governor, felt shame so many decades later.

She tries to explain. “When I was young there was something almost glamorous about having a connection with the British Empire.”

She says she used to borrow a lot of her grandfather’s old clothes. “There were silk scarves, with a nametape saying ‘Made in British India’.

“And now when I see them at the back of a cupboard, I kind of shudder and say, why would I even want to wear these things? Because the words ‘British India’ on the label seem inappropriate to wear now.”

Herbert family

Herbert familySusannah is determined to know more about her grandfather’s life in British India, and to make sense of things.

She is reading everything she can on the Bengal famine, going through stacks of her grandparents’ papers at the Herbert archive in the family home in Wales. They’re kept in a climate-controlled room, and an archivist visits once a month.

She starts to realise more about her grandfather. “There’s absolutely no doubt that the policies he implemented and initiated contributed enormously to the scale and impact of the famine.

“He had skills, he had honour. And he should not have been appointed to the post of running the lives of 60 million people in a faraway corner of the British Empire. He just should not have been appointed.”

In the family archive she found a letter from Lady Mary, her grandmother, written to her husband in 1939, on hearing he had been offered the job of governor. It’s a letter of pros and cons. She clearly had no desire for them to go, though she writes she would accept whatever decision he took.

“You read them [the letters] with hindsight, you read them knowing what the writer and reader did not know. If you could reach out to the past, you’d say: don’t do it. Don’t go, don’t go to India. You will not do a good job.”

Over the months I have been following Susannah Herbert’s journey into the past, she has had many detailed questions about her grandfather.

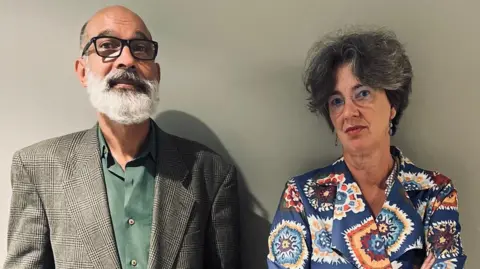

She has been keen to meet Janam Mukherjee, the historian, to ask him directly. They meet in June.

Janam admits he never imagined he would ever be sitting opposite the granddaughter of John Herbert.

Susannah wants to know why her grandfather, a provincial MP and government whip, was appointed in the first place, when he had virtually no experience of Indian politics, beyond a brief spell in Delhi as a young officer.

“It’s part and parcel of colonialism and stems from an idea of supremacy,” Janam explains.

“Some MP who has no colonial experience, who has no linguistic capacities, who has not worked in a political system outside of Britain, can simply go and inhabit the governor’s house in Kolkata, and make decisions about an entire population of people that he knows nothing about.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhile Herbert was not popular among elected Indian politicians in Bengal, even his seniors in Delhi seem to have doubted his competence, including Viceroy Linlithgow.

“Linlithgow called him the weakest of the governors in India. They, in fact, were interested in removing him, but they were worried about how that might be received,” says Janam.

“That is hard listening,” Susannah replies.

I am struck that for both there is a personal connection. Janam and Susannah had fathers in Kolkata who were little boys at the same time but were living completely different lives. They’ve both died now. Susannah at least has photographs.

For Janam, there were no pictures of his father as a child. “So what I knew was from his nightmares and from the few stories he told me of his experience in childhood, in a colonized war zone.

“I come from a sense of trying to think about my father’s very damaged life and understand how that impacts me as his descendant.”

And then he says something I wasn’t expecting.

“My grandfather also worked for the colonial police force. So my grandfather himself was complicit with the colonial system in many ways. So there are these interesting similarities in our motivations of understanding.”

At least three million people died in the Bengal famine and there is no memorial – or even a plaque – to them anywhere in the world.

Susannah can at least point to a memorial to her grandfather.

“The church where we worship has a plaque honouring him.” She explains it’s in the absence of a grave. She’s not sure where his remains are, perhaps in Kolkata.

Honour is a word that Susannah used to describe her grandfather, even though she acknowledges his failures.

“While I find it relatively easy to accept that history is much more complicated than what we were originally told, I still find it hard to envisage John Herbert […] acting in any way, dishonourably.”

Janam takes a different view. “These questions of intention have never interested me in many ways. I’m much more interested in the historical course of events because I think intentions can always mask what happens.”

Eighty years on this is still complicated, and raw. I wonder if months into her research, Susannah still feels “shame” is the right emotion to describe how she feels?

She tells me she has changed her view. “I think the word shame centres it too much on my feelings. It’s not just about me and what I think.

“It’s part of a greater project, I suppose, of understanding and transmitting understanding of how we got to where we are. We? I mean Britain, I mean, this country.”

Janam agrees that “as a descendant of a colonial official, I don’t think there is any particular shame that accrues intergenerationally. I think it’s Britain’s shame.

“I mean people died of starvation in Bengal. So I think there’s cause for historical reflection on the individual level as well as the collective level.”

Susannah is reflecting on her legacy. She wants to share her findings with her wider family, and she’s not sure how they’ll receive it.

She is hoping her children might help her work her way through the mountains of papers in the family archive in Wales.

They too are contending with a complex personal legacy, as Britain tries to figure out what to do with this difficult part of its war story and colonial past.