Whoever becomes PM will find the foreign stage a crowded one

BBC

BBCDays after the UK’s new prime minister enters Downing Street, they will board a plane to Washington for a crucial summit of the Nato military alliance.

The following week – a day after the State Opening of Parliament – they will host about 50 heads of government at Blenheim Palace for the European Community Summit.

All politics may be local, but after an election focused on domestic issues, the PM will discover fast that government is often global.

Amid this frantic round of diplomatic speed dating, they will have to confront a raft of international challenges, with wars in the Middle East and Ukraine, political instability in the US, division in Europe and threats from China.

Getty Images

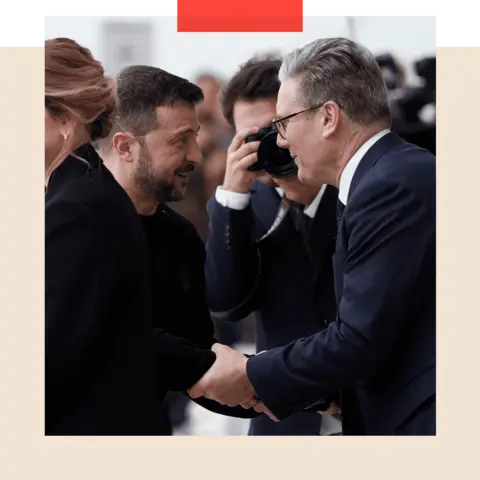

Getty ImagesRishi Sunak has faced accusations he is not interested in foreign policy, outsourcing much in recent months to Lord Cameron, the foreign secretary. Diplomats and analysts say if he were were re-elected, he could come under pressure to focus more on international affairs. And they say if Sir Keir Starmer were elected prime minister, he would be facing a steep learning curve on the world stage.

“There is no time to get your feet under the table,” says Sophia Gaston, head of foreign policy at the Policy Exchange think tank.

“Geopolitics doesn’t wait for you to swot up on your brief.”

Support for Ukraine – and Nato

The Nato summit will celebrate 75 years of the alliance, but the conversation will be dominated by what more support should be given to Ukraine and, crucially, whether it should join the alliance.

Some members are reluctant to promise automatic, inevitable membership, fearing it could escalate the war with Russia. The US says Ukraine should be offered a “bridge” to Nato, not a formal invitation.

Labour has promised to maintain the financial and military support offered by the Conservative government. But some party strategists believe that to end all doubt, they might have go further than the Conservatives to emphasise continuity.

They will not be able to offer more money or weapons because Labour is committed to carrying out a review of defence spending first that would take many months, but they believe Sir Keir might chose to offer Ukraine a faster and less conditional route to join Nato than some allies are willing to contemplate.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOfficials tell me there will also be arguments in Washington about how much Nato members should spend on defence. The current target is 2% of national output, but some allies want that to rise to 2.5%. How much will the new government want to spend when it has competing domestic priorities such as education and health? The Tories promise to spend 2.5% on defence by 2030; Labour the same “as soon as resources allow”.

Labour wants to look serious on defence while also economically responsible, so does not want to make unfunded spending commitments. But in government the party could find itself under pressure.

The Lib Dems say the 2.5% target should be “an ambition”, Reform says it should be as high as 3%, and the Green Party is silent on defence spending, although it has abandoned its opposition to Nato.

Hard choices in the Middle East

Little in the Middle East will be easy for the new government. Would it restore UK funding to Unwra, the UN aid agency in Gaza, and if so when? Would it have to end arms sales to Israel – as advocated by the SNP, Green Party and Plaid Cymru – if Foreign Office lawyers decide there is a risk they could be used to violate international humanitarian law. Would it publish that legal advice?

The government may even have to decide whether to implement an arrest warrant issued by the International Criminal Court against Israeli leader Benjamin Netanyahu if he were to pass through London. Ultimately, will the government have to decide at some point whether to back a prospective end to the fighting in Gaza that involved difficult compromises?

None would be easy choices but diplomats tell me they believe it would be harder for a Labour government because of internal political pressures. After the October 7 attacks, Sir Keir Starmer gave strong support to Israel, even appearing to suggest that it had the right to cut off water to Gaza. But as Palestinian casualties mounted and internal pressure grew, Labour has begun to temper its support for Israel, being more critical of its military operation in Gaza, backing the ICC war crimes allegations and hinting it may oppose UK arms’ sales to Israel. Those choices, diplomats say, would get only more difficult in office.

Positioning on China

Ostensibly the two largest parties have similar policies on China. The Conservatives promise to “protect, align (with allies) and engage” with China, while Labour promises to “compete, challenge and co-operate”. Foreign policy analysts tell me the difficulty for both is establishing where the line should be drawn between these competing ambitions. Labour is promising a full audit of UK-China relations. How much should the government restrict trade with China to toughen up Britain’s economic resilience? How much should the government co-operate with China on climate and health issues?

Hanging over this is China’s ambition to take control of Taiwan. Many policymakers in the US believe some kind of military action will take place by 2027. In such case, would a UK government impose sanctions on China at huge economic cost to itself? Would a UK government support any kind of US military defence of Taiwan?

“The big question for Labour is whether it believes that strategic competition is a US-China story, or whether it’s something that Britain has a role to play in,” says Sophia Gaston of Policy Exchange.

A disruptive US election?

The presidential election in November could present Downing Street with tough choices. There is a risk of political instability and violence after a close result, such as there was in January 2021.

“There may come a time sooner rather than later when the UK might be in a position where it is going to have to weigh in on questions of America’s democracy, dysfunction and commitment to its own democratic values,” says Leslie Vinjamuri, director of the US and Americas Programme at the Chatham House think tank.

“The next UK government needs to think very clearly about whether and how and when it will speak up in the event of a disruptive election.”

Regardless of who wins in November, the US is also becoming more detached from the world, and diplomats say this means the new UK government may have to choose between aligning with US and European positions on key issues like Ukraine, China, and trade tariffs on European goods.

And then, of course, there is the uncertainty of Donald Trump as US president, if he were elected. What if he sought to negotiate an unacceptable political settlement in Ukraine or launch a trade war on China – or even Europe?

Shifts in Europe

The success of nationalist parties in the European Parliament elections may complicate attempts by a UK prime minister trying to navigate a new relationship with the EU. Some leaders potentially supportive of the UK might be distracted by their own efforts to stay in power. Others might be less willing to do deals with the UK, say, on migration.

Labour has said it would want to negotiate a new defence and security pact with the EU, in a bid to formalise co-operation over issues such as the war in Ukraine, the threat from Russia, shared defence procurement, mass migration and organised crime.

But the new European Commission will not be formed until the autumn, so some in Labour fear there would be a political vacuum until then during which if they were in government, they would want to demonstrate its pro-European credentials without giving away its negotiating hand.

Labour has promised it will not take Britain back into the Single Market or Customs Union, let alone the EU (in contrast to the Lib Dems who want the UK to re-join the Single Market and the SNP which believes EU membership is the “best option for Scotland”.

Over time, European diplomats say, a Labour government might have to choose how much it is willing to align Britain’s economy to the EU’s in return for greater co-operation, on security via the new pact, or on trade via the scheduled review of the Brexit deal in 2025. This would inevitably be politically contentious because the government would have to find a balance between making economic gains and accepting EU rules over which it had no say.

The Conservatives promise to “build” on the Brexit deal they negotiated and keep removing EU laws from the UK statute book. Reform would scrap EU laws, abandon the Windsor Framework establishing Northern Ireland’s trading relationship with the EU and take the UK out of the European Convention on Human Rights.

BBC InDepth is the new home on the website and app for the best analysis and expertise from our top journalists. Under a distinctive new brand, we’ll bring you fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions, and deep reporting on the biggest issues to help you make sense of a complex world. And we’ll be showcasing thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. We’re starting small but thinking big, and we want to know what you think – you can send us your feedback by clicking on the button below.