Why are devolved issues dominating a UK election?

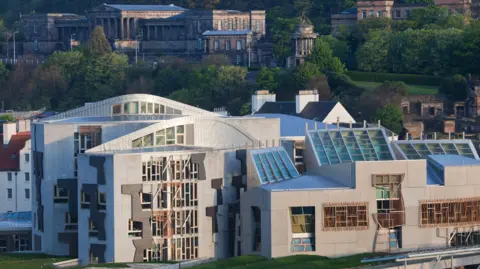

BBC

BBCThe vote on July 4 is a UK general election, and thus will not directly affect how the Scottish government delivers services north of the border.

But those services and policies which are devolved to the Scottish Parliament are still playing a huge role in the campaign.

Why aren’t Scottish politicians more concerned about sticking to reserved, rather than devolved, areas?

The advent of the Scottish Parliament in 1999 created two different sets of powers for politicians – those devolved for MSPs to work with, and those which remain reserved to Westminster and its MPs.

Devolved matters include important policy areas like health, education, housing, justice and policing, economic development and the environment.

Reserved matters meanwhile include defence and national security, foreign affairs, immigration, trade and currency.

Over the years, extra powers have also been devolved to Holyrood – including the management of certain welfare benefits and some tax-raising powers including a Scottish rate of income tax.

This patchwork of who is in charge of what can be difficult to follow – and no more so than during an election campaign, when politicians are looking to craft straightforward messages which “cut through” to voters.

When the big UK-wide campaigns are talking about the state of the health services, it can be difficult to block that out in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

And Scots are obviously going to have their views of the candidates shaped by their experience of the NHS – despite the fact it’s managed entirely from Holyrood.

Voters simply aren’t going to base their views solely on a prospective MP’s position on foreign affairs, if that party is also talking about health and education too.

It also feels like the politicians themselves don’t particularly care.

The SNP has made its record in government a prominent campaign issue. Candidates and ministers alike love to point to things they have delivered, like the Scottish Child Payment and free bus travel for under-22s.

Equally the Holyrood opposition parties have put criticism of the SNP’s record front and centre of their pitches.

The Conservatives spent the first half the campaign talking about Michael Matheson’s iPad data bill – a Holyrood disciplinary issue.

Labour, keen to take seats from the SNP, never misses a chance to paint the government in Edinburgh as being as allegedly chaotic as the one in London.

The Lib Dems meanwhile frequently major on improving access to NHS dentists and GPs.

There is an element of pragmatism to this. If waiting times and access to treatment are coming up on the doorsteps, canvassers are not going to chide voters that actually they can vote on that in 2026. They’re going to find policies and arguments to suit whatever people are most interested in.

PA Media

PA MediaAnd in fairness there are ways in which the reserved policies being discussed at this election will ultimately overlap with devolved ones.

Take health. If the next UK government were to increase health spending, that would have a knock-on effect on the Holyrood budget.

Spending in devolved areas triggers what are known as “Barnett consequentials” – the devolved administrations get a share of the funding, but can spend it on whatever they please.

In practice, consequentials resulting from health spending down south are almost always passed on to health services in Scotland, because ministers in Edinburgh don’t want to look as if they’re less dedicated to the NHS.

There are also the usual claims and counter-claims about privatisation and who is going to “save the NHS”.

So that gives candidates in Scotland a reasonable excuse to talk about health in this campaign, even though it’s devolved.

It’s also worth reflecting that just became issues are reserved, they do not operate in an entirely independent atmosphere.

There may be a devolved rate of income tax, but key measures like the tax-free allowance and National Insurance Contributions are reserved, meaning the systems are quite closely interlinked.

The same goes for welfare – many benefits have been devolved, but some like Universal Credit are still run from Westminster. Some of the current proposals to reform welfare at a UK level could thus put pressure on the system run from Edinburgh.

PA Media

PA MediaAnother quirk of devolution that impacts on this contest is what known as the pre-election period, or “purdah”.

Essentially the business of government can and must continue during the campaign. John Swinney is still the first minister, and his cabinet keep going with the day job – and civil servants support them in delivering existing commitments.

But they cannot use the machinery of government for anything which might give them an advantage in the election.

There essentially has to be a firewall between government business and party campaigning. For example when John Swinney took a train trip to mark the reopening of the Levenmouth railway line, he then had to shift to a separate party event as SNP leader rather than first minister before he could engage in any electioneering.

This isn’t just about politicians being clear about when they’re acting as a partisan party member or as a cabinet secretary pursuing government work.

It also applies to the use of the civil service, and government announcements during the campaign.

Because Mr Swinney was freshly in the door as first minister at the point the election was called, he had a whole host of announcements planned about how he would run the government.

But most of them have had to be shelved, as outlined by the head of the civil service in Scotland.

The medium-term financial strategy – which might have included future tax plans – had to be paused, along with its accompanying fiscal forecasts.

So have the planned energy strategy, just transition plan and oil and gas policy publications, all expected this summer.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThat has created difficulties for the SNP when the campaigns focus in on things like the North Sea oil and gas industry.

The government hasn’t yet published its formal strategy for the sector, and now they’re not allowed to until after the election.

But SNP politicians are asked about it constantly. They have had to stick to their interim position of stressing the importance of a “climate compatibility checkpoint”, which is much more nuanced and much harder to fit on a leaflet than the binary positions of the Conservatives (who are in favour of new licences for exploration) and Labour (who wouldn’t grant any).

The party’s manifesto ultimately plumped for an “in-between” position of assessing bids on a case by case basis.

But this is necessarily a policy formulated by party officials, rather than civil servants with reams of data and expertise to hand. And Mr Swinney is still routinely pursued to explain exactly what it means.

The Conservatives have run into similar problems around their tax claims, with the civil service distancing itself from Rishi Sunak’s attack line about the cost of a Labour government.

So it absolutely is helpful to have an understanding of what is devolved and what is reserved during this campaign, and where figures are coming from impartial government officials or partisan party campaigners.

But in the debates and doorstep encounters of the next few weeks, the lines are likely to remain pretty blurry.