Australia turned its back on Assange. Time made him a martyr

Reuters

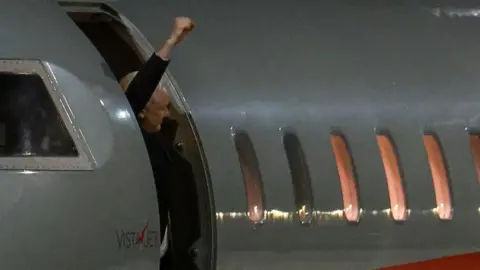

ReutersWhen Julian Assange returned home after 14 years on a chilly Canberra night, he emotionally embraced his wife and raised his fist in triumph.

A handful of supporters waved and cheered as he drove away from the air base.

But this was no hero’s welcome – there were no large crowds or champagne in sight.

However, look closely and you will see signs of just how hard Australia has worked to get the WikiLeaks founder home.

He was followed off the plane by former Australian prime minister Kevin Rudd, who is now the country’s ambassador to the US, and Australia’s High Commissioner to the UK, Stephen Smith – who oddly enough was Rudd’s foreign minister between 2007 and 2010.

And minutes after he landed Anthony Albanese addressed the nation, giving him a subdued welcome back.

“I am very pleased that this saga is over, and earlier tonight, I was pleased to speak with Mr Assange to welcome him home,” he said.

This is a far cry from the mood back in 2010, when Assange first found himself in hot water.

He had released thousands of unredacted US documents on the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq – including footage of a US helicopter firing on civilians – embarrassing Washington and allegedly endangering their informants and operatives.

Shortly afterwards Swedish authorities began chasing him over allegations he sexually assaulted two women – claims he said were politically motivated.

There was little sympathy for Assange in Canberra, so much so that he famously said the Prime Minister of the day had “betrayed” him.

“Let’s not try and put any glosses on this… information would not be on WikiLeaks if there had not been an illegal act undertaken,” Julia Gillard had said.

“And then we’ve got the common sense test about the gross irresponsibility of this conduct.”

Far from offering to advocate on his behalf, her government said it was providing ”every assistance” to US authorities and asked Australian officials to investigate whether he had broken any of the country’s laws as well.

They would later temper their language, but Gillard maintained “there’s not anything we can, or indeed, should do”.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOutwardly at least, little would change for a decade.

After trying to unsuccessfully challenge Sweden’s international arrest warrant – which he alleged was a ploy to send him to the US – Assange fled to the Ecuador embassy in London where he lived for almost seven years.

In 2019 he was dragged out of the embassy and imprisoned while he fought to block his extradition to the US.

As the case dragged on and Assange’s health declined, support for his release grew across Australia’s political spectrum. But it continued to stop short of the country’s highest offices.

The only prime minister to make big waves with comments about Assange’s freedom was Scott Morrison, when Baywatch actress Pamela Anderson toured the country to lobby on the WikiLeaks founder’s behalf in 2018.

“I’ve had plenty of mates who have asked me if they can be my special envoy to sort the issue out with Pamela Anderson,” Morrison told a local radio station, remarks Anderson called “smutty” and “unnecessary”.

‘Window of opportunity’

However with the election of Labor Prime Minister Anthony Albanese in 2022, Assange’s circle told the BBC they hoped for change.

Swedish prosecutors had dropped the rape charges, saying time had weakened the evidence. Documentaries began glamorising Assange’s work, calling him a valiant campaigner for truth, while also exposing his ill health and treatment in prison.

Then came the news he was a father to two young boys – conceived while he was in the Ecuadorian embassy and left to their mother to raise on her own.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesNational animosity or ambivalence towards Assange was turning to pity. A poll from earlier this month indicated a large majority of Australians – 71% – said the US and UK should be pressured to close Assange’s case.

And Mr Albanese was viewed as an ally. He had long said he didn’t support many of Assange’s actions, but that “enough is enough”.

After taking office Mr Albanese reaffirmed his position, but stressed “not all foreign affairs is best done with the loud hailer”.

Many of Assange’s supporters believed the alignment of a Labor government in Australia and a Democratic administration in the United States was a window of opportunity, says political scientist Simon Jackman.

“But we’re coming up on election in the United States, the window for getting this done was starting to close,” the Honorary Professor of US Studies at the University of Sydney told the BBC.

“And so I think that was adding a little bit of energy… a little further impetus on the Australian side.”

During a state visit to the US late last year, Mr Albanese confirmed he raised Assange’s plight with President Biden directly.

And in February the Australian parliament – with the prime minister’s support – voted overwhelmingly to urge the US and the UK to allow him to return to Australia.

In the US, the case had long been considered “troublesome” for the Department of Justice and for successive presidential administrations, former CIA chief of staff Larry Pfeiffer told the BBC.

Add the pressure from Australia and frustration in the UK at the lengthy nature of proceedings there – friction in two important relationships – plus the passage of time and the prospect of yet another appeal, and the US had become very keen to resolve the case.

“I think there were people within the Justice Department who said, ‘Hey, you know, the guy did it to himself largely, but he’s pretty much done his time’,” Pfeiffer said.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut getting the deal over the line is credit to Australia, he adds.

“This is testament to how quiet diplomacy can work.”

Still a polarising figure

In the hours after the plea deal was announced, Stella Assange said people had come to see her husband differently.

“The public climate has shifted and everyone understands that Julian has been the victim,” she said.

In reality, he is still an extremely polarising figure in Australia.

Alexander Downer – a former Australian foreign minister and its High Commissioner to the UK between 2014 and 2018 – has long argued Australia should not intervene in the saga and said Assange should not expect a hero’s welcome home.

“What he did was a criminal offence, and it was a terrible thing to do, morally as well, and endangering people’s lives in that way,” he told BBC’s Radio 4 programme.

“Just because he’s Australian doesn’t mean he’s a good bloke,” he added.

On the other hand, Greens Senator Peter Whish-Wilson said Assange was persecuted for “telling an awful, inconvenient truth about war crimes”.

“The persecution of Julian Assange has shone a light on a broken legal system, one in which an innocent man must plead guilty to be free,” he said.

Others sit in the grey middle.

Barnaby Joyce has long been one of the MPs leading calls for Assange’s release – arguing his treatment has been horrific and that the extraterritorial aspect of the case is worrying.

But he always clarifies in the next breath that he doesn’t believe what Assange did was right.

“I’m a former serving member of the Defence Force… I’m not here to give a warrant to his character,” he told the BBC News Channel.

Some have spoken in support of his freedom, but voiced discomfort at his characterisation as a hero and journalist. Others pointed to concern over claims of election interference – even the characterisation by US officials that WikiLeaks is “a nonstate hostile intelligence service”.

Even Mr Albanese trod a delicate line: “Regardless of your views about his activities, and they will be varied, Mr Assange’s case has dragged on for too long,” he said in parliament on Wednesday.

With his feet now firmly on Australian soil, it appears Assange will finally be able to get on with his life – starting with his 53rd birthday next week, which he’ll celebrate alongside his family for the first time in 14 years.