The winners and losers in South Africa’s historic new government

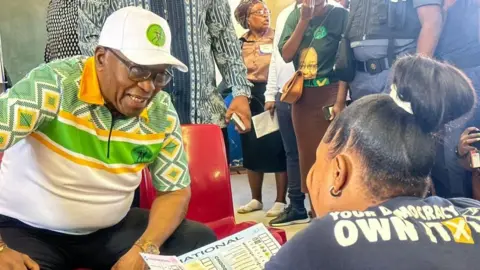

EPA

EPALiving up to his reputation as a skilled negotiator, South Africa’s President Cyril Rampahosa appears to have outmanoeuvred his main coalition partner – the Democratic Alliance (DA) – in talks over the formation of a new government, while also taking steps to neutralise radical opposition parties demanding the nationalisation of white-owned land.

Mr Ramaphosa announced a 32-member cabinet on Sunday, which saw him keep 20 posts – more than 60% – for his African National Congress (ANC).

In contrast, he gave the centre-right DA six seats – less than 20% – despite the party demanding 30%, following a power-sharing deal it signed with the ANC after the 29 May election failed to produce an outright winner.

But to double the DA’s representation, Mr Ramaphosa also appointed six of the party’s officials as deputy ministers, including in finance where the ANC’s Enoch Godongwana – respected by both the business sector and trade unions – has remained in charge.

The appointments came after tough negotiations with the DA and a furious exchange of letters, which saw Mr Ramaphosaa accuse the party of trying to form a “parallel government” in breach of the constitution.

Mr Ramaphosa further diluted the DA’s influence in the new cabinet by giving a another six posts to smaller parties – from the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) to the Afrikaner nationalist Freedom Front Plus, making it the most ideologically diverse government in South Africa’s history.

In keeping with tradition since the end of the racist system of apartheid in 1994, the cabinet also represents all race groups, with a significant number of portfolios given to members of the white, coloured – as people of mixed race are referred to in South Africa – and Indian communities.

This comes after an election in which voters showed that they “don’t care if the cat is black or white, but whether it catches the mice”, political analyst Thembisa Fakude told the BBC.

However, there is still resistance to Mr Ramaphosa’s decision to sign a coalition deal with the DA.

Led by John Steenhuisen, the party is often accused of trying to protect the economic privileges that white people built up during apartheid – a charge it denies.

“Oil and water do not mix,” a black security guard told the BBC.

Billing his cabinet as a government of national unity, Mr Ramaphosa also gave a deputy ministerial post to the Muslim Al Jama-ah party, in a clear sign that he intends to continue backing the Palestinians over Israel, despite opposition from the DA.

This perception was strengthened by the appointment of former Justice Minister Ronald Lamola as foreign minister.

A lawyer, Mr Lamola led South Africa’s opening arguments in the genocide case it brought against Israel at the International Court of Justice.

He takes over from Naledi Pandor, who failed to be re-elected to parliament.

Apart from backing the Palestinian cause, she also strengthened South Africa’s ties with the Brics club of nations, which is seen as a rival to the West, and Russia.

Political analyst Prince Mashele told the BBC he doubted that South Africa would remain a major force internationally, as the ANC had lost its political dominance.

He argued that South Africa’s partners in Brics – which includes Brazil, Russia, Indian and China – would “see that they are dealing with a weak partner”.

EPA

EPAMr Ramaphosa was forced to appoint what he has billed as a government of national unity after the ANC lost its parliamentary majority for the first time.

He was voted in for a second term by parliament only after the DA agreed to back him in exchange for seats at the top table of government.

The ANC got 40% in May’s election, while the DA came second with 22%.

The DA initially demanded 11 cabinet posts – along with the deputy presidency or the post of minister in the presidency for Mr Steenhuisen.

In the end, Mr Steenhuisen was forced to settle for the post of agriculture minister.

But Mr Steenhuisen welcomed the deal, saying the “DA is proud to rise to the challenge, and take our place, for the very first time, at the seat of national government”.

He said the DA had “refused to accept watered-down compromises and… drove a hard bargain at times to ensure that the portfolios we get are of real substance”.

Mr Steenhuisen’s position is likely to help allay the fears of the country’s white farmers, many of whom feel threatened by the demands of what are now the two biggest opposition parties – former President Jacob Zuma’s MK party and Julius Malema’s Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) – for the nationalisation of white-owned land.

But the DA leader’s appointment was offset by Mr Ramaphosa’s surprise decision to give the new land reform ministry to the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) – a former liberation movement which fought white-minority rule under the slogan “Africa for the Africans”.

The PAC waged its election campaign under the slogan “Our land, Our Legacy”, and called for the “decolonization and the restoration of land to its original owners”.

The portfolio, which was previously combined with agriculture , will be held by PAC leader Mzwanele Nyhontso.

The PAC’s decision to serve in government for the first time ever is likely to help Mr Ramaphosa fend off criticism from MK and the EFF that he has betrayed the liberation struggle by forming an alliance with the DA.

Mr Ramaphosa kept all the economic portfolios for the ANC, dropping plans to give the trade and industry ministry to the DA after strong resistance from within his party, as well as the black business lobby and the trade union movement.

They believed that handing the portfolio to the DA would undermine the ANC’s black economic empowerment policies. The pro-free market DA opposes the policies, arguing that they stifle investment, fuel corruption and simply enrich the ANC’s business cronies.

In his regular column on the TimesLive news site, former Business Day editor Peter Bruce said the ANC’s top brass “couldn’t bear the prospect of the DA anywhere near the economic levers”, forcing Mr Steenhuisen to settle for agriculture in a “mediocre trade” for the trade and industry ministry.

Political analyst Ongama Mtimke told the BBC that the portfolios retained by the ANC were important in tackling racial inequality, and Mr Ramaphosa’s choices were intended to “show to the comrades that we are still on track as far as advancing the revolution is concerned”.

But Mr Fakude said the ANC and DA were likely to find enough common ground on economic policy.

The ANC had shifted to the centre since it took power three decades ago, though it might still disagree with the DA over issues such as privatisation, Mr Fakude said, adding: “Other than that I think they do share a lot of things in common.”

Mr Ramaphosa gave the DA other key portfolios – including basic education in a nation where literacy levels are low and language policy in schools is a deeply emotive issue, public works and infrastructure, and home affairs.

The latter is seen as a political hot potato – as Mr Fakude pointed out, it “deals with the borders and illegal African immigration into South Africa”.

The public works department has been embroiled in several corruption scandals and the DA has vowed a “zero-tolerance” approach to tackle the problem.

Mr Ramaphosa gave two portfolios to the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP). Though allied with the DA, the party has adopted a neutral posture since the poll, and urged the two big parties to resolve their differences as they haggled over the cabinet’s composition.

Mr Ramaphosa gave its leader Velinkosi Hlabisa the ministry of cooperative governance and traditional affairs. The IFP is close to the Zulu monarchy, with Mr Hlabisa’s appointment seen as another move by Mr Ramaphosa to neutralise the threat posed by Mr Zuma, who has called for greater powers to be given to South Africa’s largely ceremonial monarchs and chiefs.

Mr Ramaphosa also gave the all-important police ministry to an ANC leader from Mr Zuma’s home province of KwaZulu-Natal, which has a long history of political violence.

Senzo Mchunu succeeds another ANC leader from KwaZulu-Natal, Bheki Cele, who was not re-elected.

Mr Cele largely failed to contain violence in the province, with more than 300 people killed in riots following the imprisonment of Mr Zuma in 2021 for contempt of court after he defied an order to cooperate with a commission of inquiry into corruption during his presidency.

KwaZulu-Natal is likely to face a renewed threat of unrest when Mr Zuma goes on trial, expected to be next year, on charges of corruption over an arms deal negotiated in the 1990s.

Mr Zuma denies any wrongdoing, and sees the case as politically motivated.

Having deep animosity for Mr Ramaphosa who ousted him as president in 2018, the former president campaigned for MK after breaking ranks with the ANC last December.

He led MK into coming third in the election, playing a major role in depriving the ANC of its parliamentary majority.

With the ANC and DA now joined at the hip, MK will assume the role of the official opposition, setting the scene for fierce confrontation with the ANC and its new coalition partners.

More BBC stories on South Africa’s election:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBCGo to BBCAfrica.com for more news from the African continent.

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, on Facebook at BBC Africa or on Instagram at bbcafrica