North London is humid and Rob White is tired.

“We had ridiculous storms here last night,” he says.

“I woke up at 4am and it was like someone switching a neon light on and off in my room.

“Even at the age of 60, that takes me somewhere.”

White is aware of the cliche.

“The clap of thunder, the flash of lightning, it is almost lazy as a plot device isn’t it?” he says.

“You see it in movies, in books, in plays – it goes all the way back to Greek tragedy.”

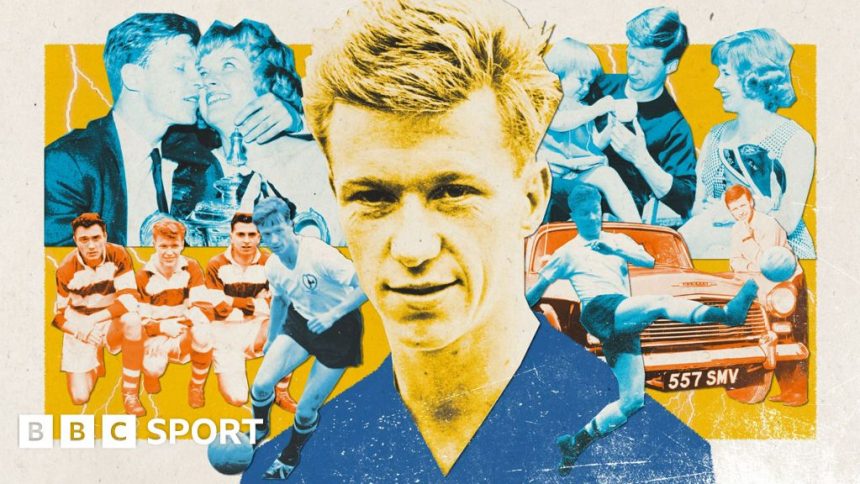

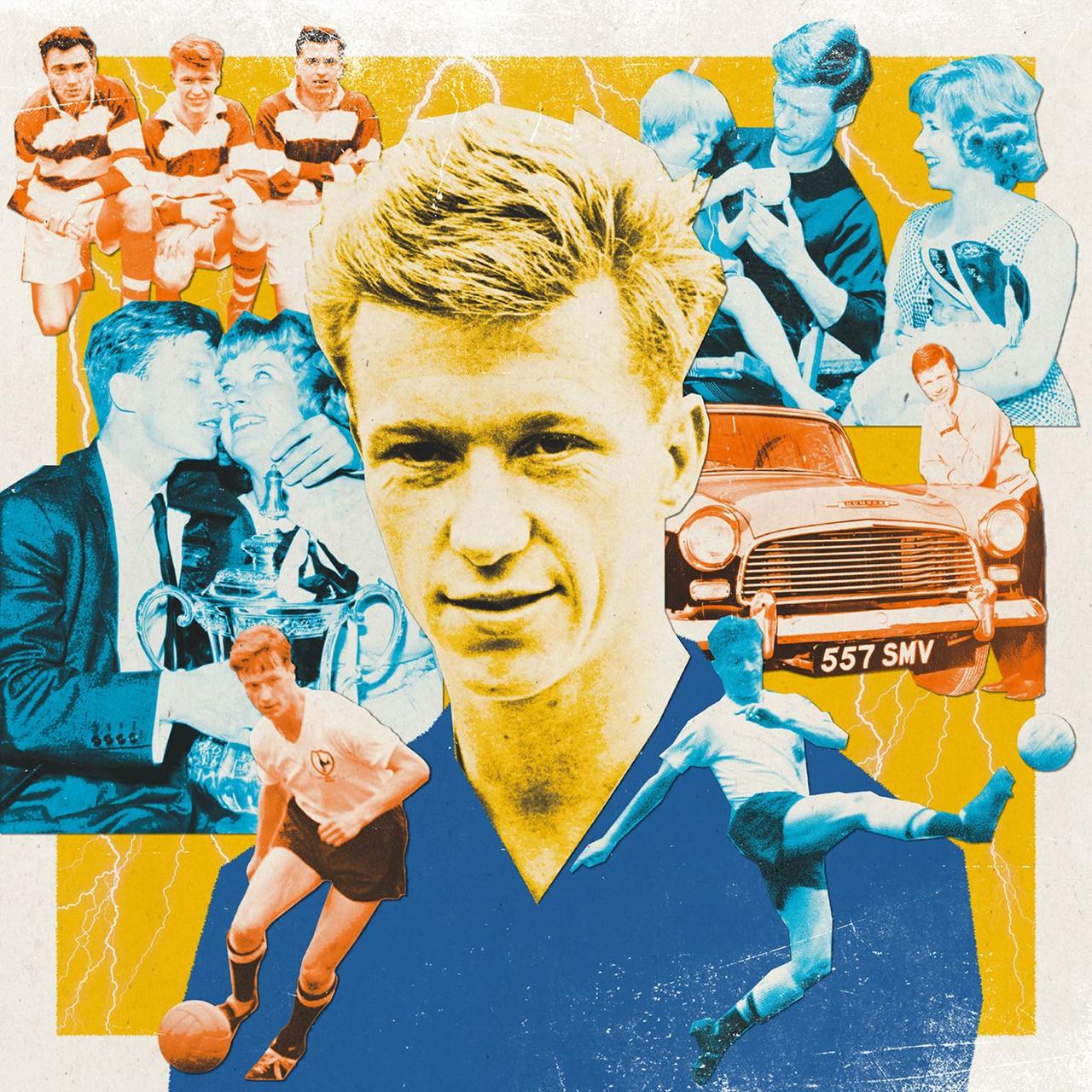

But for his story, it is undeniable and unavoidable. Every bolt lands in the same place: 21 July 1964.

Sixty years ago, a summer storm erupted over Essex and lightning struck a lone golfer.

John White, 27, was found crouched and scorched under a tree, the rings on his fingers fused to the shaft of the club he was clutching.

Tottenham and Scotland had lost one of the finest footballers of his generation – a Double winner, with a European Cup Winners’ Cup medal to his name – at the height of his powers.

Rob, just six months old at the time, had lost a father.

His search has continued ever since.

Pat Jennings (front, far right) and Jimmy Greaves (behind Jennings) attend White’s funeral on 25 July 1964

Rob has spent his life trying to unravel a death and reveal its victim, listening at closed doors and investigating sliding doors.

The day he knows best in his father’s life is the last.

It is one littered with chance encounters and alternate universes, any of which would have led John out of a lightning bolt’s path.

On the fateful morning of 21 July 1964, Tottenham’s players gathered for some team photos and gentle pre-season training at White Hart Lane.

Having finished in the top four in seven of the previous eight seasons, they were an established power, with an attack centred on Jimmy Greaves’ power and Cliff Jones’ tricky.

John White’s gifts were more subtle. He had a silken first touch, an astute passing game and an ability to lose his marker that, combined with his slight frame and pale complexion, earned him the nickname ‘the Ghost’.

Bill Nicholson knew John’s value. Having lost Dave Mackay to a broken leg and captain Danny Blanchflower to retirement, the manager had told John that his next Tottenham team would be built around him.

White (far right) in action in the 1962 FA Cup final against Burnley. His Tottenham side retained the FA Cup with a 3-1 win in front of 100,000 spectators

That was all to come, though. This wasn’t the time of year for serious business.

After training, barely blowing, John stripped down to his vest and pants to take on team-mate Terry Medwin in an indoor tennis match, rather than head straight home.

When John returned to the dressing room, he was confused. His trousers were missing. Ten minutes before, a smiling Jones had driven out of White Hart Lane, waving them out of his car window in glee at a well-executed prank.

John eventually found a pair to borrow, finally returned home and, despite the day drawing on, said he was going to play golf.

His young wife Sandra, juggling Rob and his two-year-old sister, suggested he shouldn’t. They argued.

Delay heaped on delay. The sky darkened.

A compromise was found. Sandra dropped John off at Crew’s Hill golf course. He headed into the club shop and bought a pack of three balls. As he left, he bumped into Tony Marchi, another Tottenham team-mate. Having asked about for a playing partner at training earlier in the day, John asked for a final time. Did Tony fancy playing with him?

“As far as we know, that was the last conversation my father had,” says Rob.

“The last thing that Tony thought as he watched my dad go out was: ‘John is going to get really wet out there this afternoon.'”

Marchi, having played his own round already, opted against joining John. The final sliding door shut. John walked out another and on to the course.

“I know that Tony [who died in 2022] always wished he could have just had another paragraph of conversation with my dad,” says Rob. “Because if he had, my dad wouldn’t have been in that place at that time.”

The White family in 1964, with two-year-old Mandy sitting on John’s knee and a young Rob, wearing one of John’s Scotland caps, being held by Sandra

The landlord emerges from behind a curtain, cigarette in mouth, thinning hair slicked back, and nonchalantly hands out a collection of pistols to the suited young men on the other side of the bar.

Each handles them with awed reverence, spinning the barrels and staring down the sights.

At one point, one of young men, blonde and slight, takes a handkerchief out of his pocket and blows his nose.

And all the time, an unseen Pathe newsreader chatters away over the top.

It is a film from 1962 – a different time when top-flight footballers would be little more than extras in a news report about a gun-collecting publican in north London., external

John White and his team-mates played their parts well, looking on in due awe as their host spun a gun on his finger and slotting it back into his holster.

For Rob, the footage is part of a patchwork he has been stitching together over the past 60 years.

The first pieces came when, aged nine, he sneaked up into the attic of the family home and opened up a cardboard box.

“It was like Tutankhamun’s tomb – it had scrapbooks, newspapers, programmes, boots, medals, a couple of Scotland caps, a shaving kit that smelt of Old Spice,” Rob says.

“As a kid, I would sneak up into the loft and essentially grieve and get really quite sad looking at this stuff.

“It was as if my Dad was one of those wire mannequins that sculptors might use; I knew ‘the Ghost’, that my dad was something, but finding this stuff allowed me to put texture on that outline.”

White and Greaves celebrate an FA Cup final victory at Wembley

Just as on the pitch though, tracking down John was not easy.

Rob’s mother Sandra could remember driving up to the course to pick up her husband, seeing the clubhouse surrounded with police cars and then, such was the shock, little else from the next five years of her life.

In the wake of John’s death, the sideboard trophies, celebratory photos and any trace of his existence were tidied away. In their place, a culture of stoicism, silence and secrecy dominated. His father was rarely spoken about – a subject too sore for anyone to know how to handle.

“Most families have a story that as a kid you don’t know the full details of, but you know never to ask about,” says Rob.

“Maybe you are told something once, or a door is half-open and you hear something. You can’t quite piece it together, but, as humans, we create our own narrative, filling in the gaps with information that may, or may not, be right.”

For Rob, there was plenty of information to fill in the gaps.

John’s life was documented in an uncommon depth for his era.

People shared hundreds of photos, thousands of memories and the odd piece of footage.

Usually the film was match action, but occasionally it was something rarer and, in many ways, more precious – an afternoon John spent in a pub with its eccentric landlord and a Pathe film crew for instance.

Tottenham players at their 1962 Christmas party with Tony Marchi (far left), Jimmy Greaves (centre), Dave Mackay (third from right) and John White (second from right)

Too often, though, the character lacked depth: as thin as the page of the comic he seemed to spring from.

“He was this kind of Roy of the Rovers figure and as I got older I got frustrated and almost embarrassed by people having a better knowledge of my dad than I did,” Rob says.

“Part of the joy of having a father is finding our own identity – there is a little blueprint there and if we are lucky we follow the good bits and jettison the bad bits – but I didn’t have that.

“There is still a kid in me that wants to know the simple stuff: what he smelt like and sounded like, a bit more about him, rather than this persona. That is the eternal frustration.”

Rob channelled that frustration into a book – The Ghost of White Hart Lane – interviewing family members, former team-mates, friends and acquaintances, to try and discover the man behind the myth.

And gradually he found him.

Rob heard about the sadness and homesickness that would grip John each winter in London. He heard about the time he drove home dangerously drunk, clipping the White Hart Lane gates in his car. Most revealingly, an uncle told Rob about the child that John had fathered in Scotland and left behind before he travelled south, played for Spurs and met Sandra.

“Part of me has always been trying to live up to this person who was absolutely perfect, who was idolised not just by the family, but by hundreds of thousands of people,” says Rob.

“To find out he had defects and weaknesses, that he struggled with confidence, mental health and seasonal affective disorder, that he had made mistakes – if I had found all that out earlier, it would have made more sense to my life.

“If we know our parents are fallible, it really makes us understand that we can make mistakes. We don’t have to know all the answers.”

John’s absence shaped Rob as surely as his presence would have.

Rob is a still-life photographer – “I have always been looking for those details and clues” – and is also training as a counsellor.

Later this month, he will be in the audience at Tottenham Hotspur Stadium for the first performance of a play he has helped produce about his father’s life.

“It is something I talk about with my own therapist,” he says. “Having seen life breathed into the story at the read-throughs, it reinforced the reasons I wanted to get involved with the project.

“I think there is something of trying to bring my dad back to life.”

After two nights in Tottenham, the play will then transfer north, taking the opposite journey to the one John took in life, for a stint at the Edinburgh Festival.

There are some things that remain lost. Rob is still searching for a recording of John’s voice. One of his match-worn Tottenham shirts remains elusive.

But over the decades, he has found much more: an understanding and an empathy for the father he never knew.

White is an avid Tottenham fan and lives less than half a mile from Tottenham Stadium

Previously on Insight

-

-

Published1 day ago

-

-

-

Published5 days ago

-

-

-

Published7 days ago

-

-

-

Published26 June

-

-

-

Published20 June

-