Which prisoners will be released from jail early?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe government has announced emergency measures to deal with prison overcrowding in England and Wales.

These include early release for some prisoners when they have served 40% of their sentence.

This will not apply to inmates serving sentences for serious violent offences or for sex offences.

How many people are in prison?

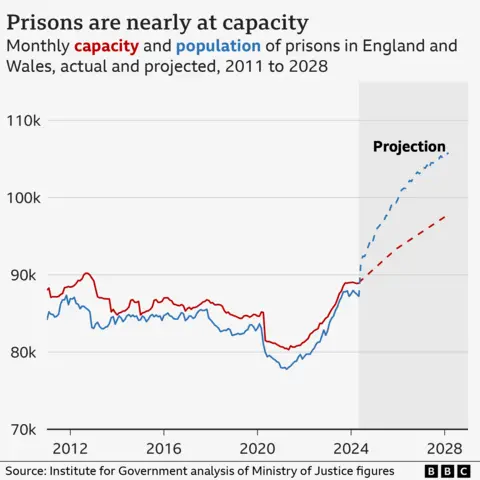

Ministry of Justice data shows the total England and Wales prison population on 12 July was 87,505, close to the record high of 88,000 in 2011.

And the “usable operational capacity” – the total number of people a prison can hold while taking into account issues like control and security – was 88,956, leaving spare capacity of just 1,451 places.

This is well above the prison service’s own measure of a “good, decent standard of accommodation”, which at the end of June was 79,698.

At current rates, the prison population is projected to rise by about 19,000 by 2028, while capacity is set to rise by 9,000.

Prisons in Scotland have also had to release people early to ease overcrowding. There were just over 8,000 people in prison in Scotland last week.

Last year, prisons in Northern Ireland had an average daily population of 1,685, a figure which has risen in recent years.

This picture is why prison governors wrote to party leaders during the election campaign, to warn: “Within a matter of days prisons across the UK will be full” and that this would put the public at risk.

The governors argued that this was because the courts would soon have nowhere to place serious offenders.

In 2018 – the latest year for which comparable data is available – England and Wales had 150 prisoners per 100,000 people, the highest proportion in Western Europe.

Spain (138 per 100,000) and Portugal (126 per 100,000) were the two western European countries with the next highest rates of imprisonment.

Why have prisons become so full?

The Institute for Government think tank says part of the answer is longer sentences.

In 2023, the average prison sentence given in the Crown Courts in England and Wales, which deal with more serious offences, was more than 25% longer than in 2012.

For some crimes, the increase has been even greater. Sentences for robbery, for example, were 13 months longer on average in 2023 than in 2012, a rise of 36%.

Longer sentences mean more people in prison at any given time.

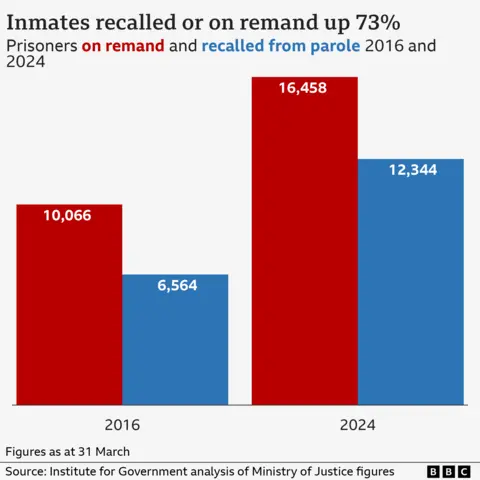

Another part of the answer is the increase in prisoners on remand, who are waiting for their trial to start, or to be sentenced.

In March this year the remand prison population stood at 16,458, a record high. In 2016, it was about 10,000.

Some of this increase has been driven by a record number of Crown Court cases waiting to be heard.

More people than before are also being returned to prison for breaching their release conditions.

In March, the number was around 12,000 – another record high – and roughly double the number in 2016.

Why not build more prisons?

In its 2021 Spending Review the then Conservative government said it would build an extra 20,000 prison places in England and Wales “by the mid-2020s”.

But only about 6,000 have been built.

The chief civil servant in the Ministry of Justice wrote in July last year that only £1.1bn of the £4bn committed to this prison building programme had been spent.

One of the obstacles has been the planning system and local objections to new prisons, including from some Conservative MPs.

The Labour government says it wants to continue building the remaining prison places but has not said when they will be completed.

The Ministry of Justice estimates that the average direct cost of funding each prison place in England and Wales in 2022-23 was £51,108.

How will Labour tackle the prisons problem?

The early release of inmates, to ease pressure on prisons, also happened under the Conservatives and under the last Labour government.

The emergency measures being announced now will mean some prisoners will be released after serving 40% of their sentence, rather than 50%.

This will not apply to those serving sentences for serious violent offences – of four years or more – or for sex offences.

Prisoners serving sentences for domestic abuse offences will also be exempt.

Instead, shoplifters and those convicted of drugs offences are among those likely to be released early.

Sources say it will most likely amount to a number in the low thousands leaving prison early

There are signs Labour will take a different approach to prisons.

Before he was appointed the new prisons minister, James Timpson, in a Channel 4 interview, stressed the need to break the cycle of re-offending by giving ex-offenders more job opportunities, something he has done through his family firm Timpson.

The key cutting and shoe-repair company says around a tenth of its employees are former prisoners.

Mr Timpson also spoke about reducing sentencing and sending considerably fewer people to prison than we currently do.

“So many of the people in prison in my view shouldn’t be there. A lot should but a lot shouldn’t, and they’re there for far too long” he said.

The Conservatives’ Neil O’Brien is among critics of the plan and has argued that “prison works”.

But this seems likely to be a government that will try to go down the road of reform.

The absence of public money for considerably increasing the size of the England and Wales prison estate, or restoring spending on the courts system will, in any case, leave little alternative.

But, before it can do that, the first priority for ministers is likely to be simply to prevent the prisons from overflowing.