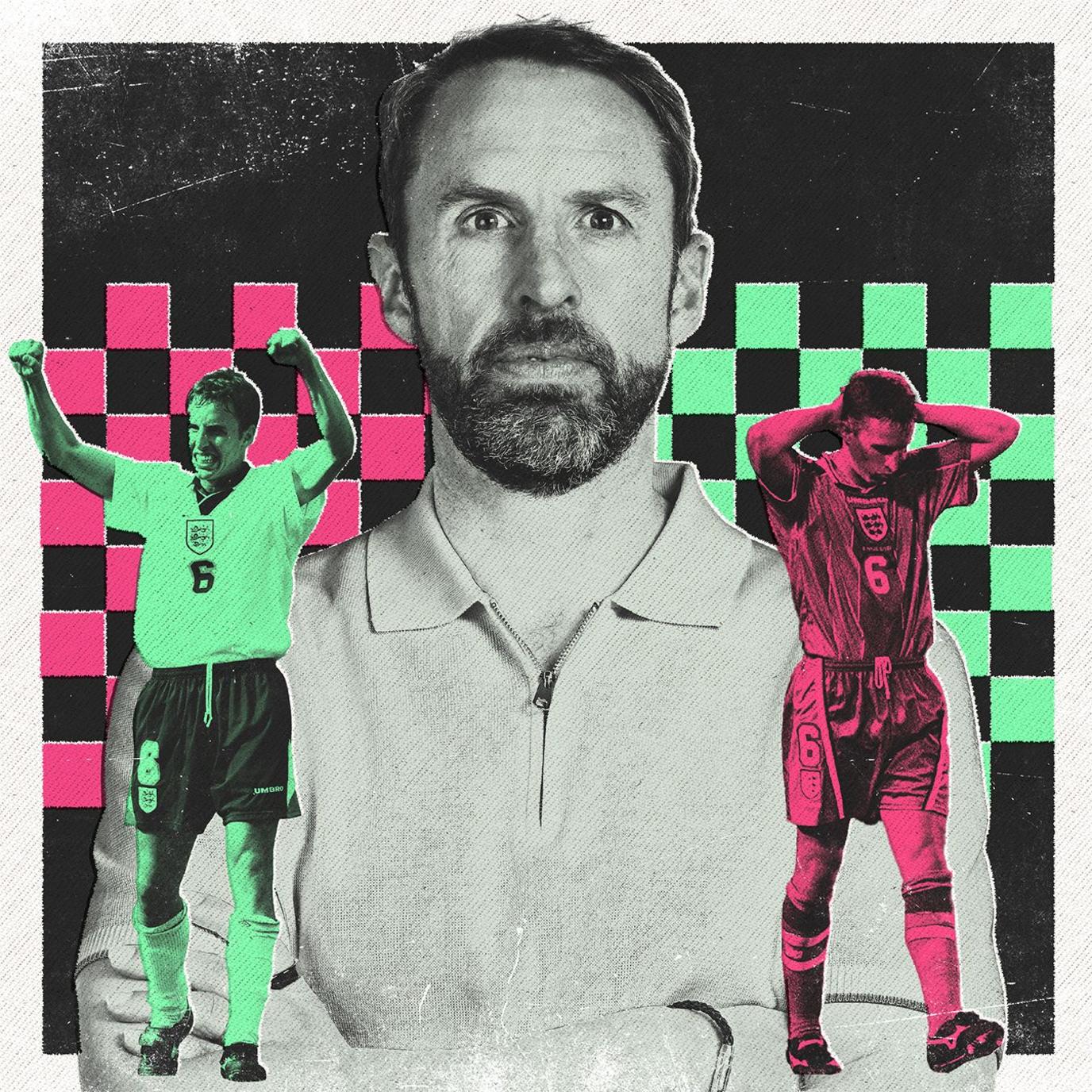

The enduring themes of Southgate’s England story

- Published

It is difficult to trace the spread of a viral internet sensation.

It might have begun with Youtube user Quincey11, external and his mates in front of the fruit machine and bar bunting of their local.

By the time of the quarter-final win over Sweden, it had bloomed into sing-a-longs across England., external

Natasha Hamilton – Atomic Kitten’s lead singer – recorded her own version around the same time, swooping up and down the octaves on her sofa., external

Finally, in an echoing Luzhniki Stadium in Moscow, more than an hour after the semi-final defeat by Croatia, a group of England fans kept the chorus rolling on and on, external as the man himself, tired, sad and proud, came to thank them for their support.

It was the unlikely sound of 2018’s endless summer: noughties number one ‘Whole Again’ exhumed and reworked as a tongue-in-cheek tribute to Gareth Southgate.

Six years on, it is still part of the songbook. And, if anything, it has grown more fitting.

Sentimental, but uncertain. Affectionate, but weary. Because the relationship between Southgate and England has never been straightforward; the frisson of 2018 has, at times in Germany, turned to friction.

For much of Euro 2024, everyone was barely keeping up appearances. For Southgate and England’s fans, it felt like a marriage of convenience crumbling to a mutually welcome end.

But, if this is where the two part, it is a relationship that finishes in a better place than anyone had a right to expect.

In 2018, Southgate’s England team were the first in 28 years to reach a World Cup semi-final

Twenty-eight years ago, Southgate was facing a very different crowd, with very different musical tastes.

On Sunday, 23 June 1996, 30,000 punks had gathered in Finsbury Park for the Sex Pistols’ Filthy Lucre reunion tour. Expectation was high. The band hadn’t played in Britain for 20 years.

Rock-and-roll royalty were gathered backstage. Oasis frontman Liam Gallagher sat smoking with actress Patsy Kensit and a group of friends. Jonny Depp clutched the hand of then-girlfriend Kate Moss.

None of them were invited to introduce the headliners.

Instead it was Southgate, clean-cut and fresh-faced, who stared out at the black leathers and bright hair and, speaking into the microphone, welcomed John Lydon and the band to the stage.

Stuart Pearce had been the instigator.

England manager Terry Venables had been concerned about granting Pearce permission to go to the gig. But the company of Southgate – no punk fan, but curious and keen to break the monotony of their tournament base – was the clincher.

What could go wrong with Southgate, the most sensible of the squad, alongside Pearce?

In the end, it went very right. Pearce and Southgate’s brief appearance on stage was greeted with roars from the crowd.

“Twelve months earlier I wouldn’t have been asked to announce the Croydon Male Voice Choir,” Southgate joked a few months later.

“The whole thing was bizarre, but it was typical of how the tournament took off.”

Southgate had only broken into the England team a few months before, but played every minute of Euro 1996

Southgate’s own profile had risen sharply.

He had only been a central defender for a year, having been converted from a midfielder by Aston Villa manager Brian Little.

He made his England debut in December 1995. His first international start had come just a couple of months before Euro 1996.

Yet, he had become integral, playing every minute of the tournament alongside Tony Adams in the heart of the defence.

It was a team with a wild, chaotic side. A pre-tournament trip to Hong Kong had included an infamous night out with bottles of spirits being poured down players’ gullets while they reclined in in a dentist chair. On the flight back, seats and TV screens had been damaged by mile-high high-jinks.

Southgate wasn’t on the night out. And, while the squad took collective responsibility for the plane damage, it was difficult to imagine even a fraction of the blame belonged to Southgate.

As a teenager at Crystal Palace’s Mitcham training ground, he had stuck out; a little more provincial, a little less loud. His considered, precise way of talking earned him the nickname ‘Nord’, in a nod to television host Denis Norden.

His youth-team manager warned him that he would need to be tougher mentally and physically to progress to the senior side.

Quietly, Southgate took on the challenge, filling out and finding his voice.

One evening, he misjudged it. After a youth tournament in Italy and an out-of-character evening drinking tequila, he vomited over Palace chairman Ron Noades on his way back to his hotel room., external

Typically, Southgate had Noades’ clothes dry-cleaned the next morning.

It was a rare, possibly solitary, misstep.

By 23, Southgate was named Palace captain, leading them to promotion out of the second tier and tangling with Roy Keane in the FA Cup semi-finals., external

Whatever he came up against – older team-mates, aggressive opponents, a switch of clubs, a change of positions – he stepped up and surprised those who thought his careful demeanour indicated a soft centre.

So, three days after the Sex Pistols gig, when England had exhausted their supply of regular penalty takers in the semi-final, Southgate, the newest and least experienced of the team, steeled himself and stepped up again.

“I was a volunteer, really,” Southgate said in 2018.

“The type of character I was, I felt you should put yourself forward.”

It wasn’t the first time.

In October 1992, one of Southgate’s Palace team-mates had lost his nerve over a late spot-kick to win a game at Ipswich. Southgate had taken it on instead, hitting the post. Palace were ultimately relegated on goal difference.

Southgate hadn’t taken a penalty since.

His strike at Wembley was solid, but too central. Germany goalkeeper Andreas Kopke guessed right and blocked with relative ease.

The ball ricocheted away, and, from Wembley outwards, a bubble burst and a world crashed down.

The next morning, Southgate flew to the Indonesian island of Bali with his girlfriend, attempting to escape the emotional aftershock.

A few days into their holiday, while trekking up a volcano, a local man asked Southgate if he was English. On receiving confirmation, his face lit up. “You, penalty drama,” he said.

Southgate returned to sacks of supportive letters from fans who had seen how the same shootout experience six years earlier had chewed up Pearce and Chris Waddle. One was from Prime Minister Tony Blair.

Southgate gave an interview later that summer., external

“I don’t think you ever get that sort of thing out of your system,” he said.

“I’m sure people will always say: ‘He was the idiot who missed the penalty.’ But hopefully I’ve got enough time in my career to do other things.

“I’ve got the ambition and the ability to make people remember me in other ways.”

Southgate’s penalty – England’s sixth in the semi-final shoot-out defeat by Germany – was only the second of his professional career

Still, occasionally, one will wash up on a social media timeline. A moment from a past as distant as a desert island.

A recommendation, external for fish and chips in Wetherby.

An exclamation, external about the cost of text messaging in Switzerland.

An idle thought, external about the lack of innovation in pitch marking.

For four years, between 2009 and 2013, Gareth Southgate was, for the first time in his adult life, adrift from the dressing room.

His managerial career was stalled. He had taken on the Middlesbrough job, switching straight from playing to managing in the top flight, aged just 35.

However, two mid-table finishes followed by relegation to the Championship brought about his departure.

It is the point where it can go south for some footballers – trying to fashion the next stage in a career that has left then awash with time and cash, but short of options and impetus.

But Southgate found that Mitcham mentality, talking, learning and working to make the second act of his life a success.

He travelled to matches at home and abroad, from the grassroots to the shiniest showcases. He did media work and had an 18-month stint looking at youth development for the Football Association.

Most importantly, he also knew what he didn’t want to do. After impressing FA bosses, he was widely touted as favourite for the organisation’s newly created technical director post.

But, rather than be drawn deeper in the FA’s corporate organogram, he left.

When the chance to succeed old friend Pearce as England Under-21 coach arose, a role in the dressing room rather than a meeting room, he took that instead.

Like on the pitch though, for all the hard work and wise moves, chance plays a part.

When England melted down against Iceland in the last 16 of Euro 2016 and Roy Hodgson resigned, Southgate was among the contenders.

Not everyone was convinced. He was a rather cosy, company candidate.

Harry Redknapp described the prospect of Southgate as England manager as “scary”, advocating for the more experienced Steve Bruce or Sam Allardyce instead.

Southgate seemed to come to the same conclusion. He ruled himself out of the running, saying the job had come at the wrong time, and Allardyce was appointed.

But 67 days later, the post was back vacant.

Allardyce had been filmed by undercover reporters posing as Far Eastern businessmen. While the fabled ‘pint of wine’ captured in their covert video was a trick of the light, Allardyce’s comments were all too real.

He suggested it was possible to circumvent rules on third-party player ownership. He mocked his predecessor Hodgson and criticised his assistant Gary Neville.

His position was untenable. Southgate was asked if he would step into the breach and lead the senior team on an interim basis. This time he agreed and has never left.

Southgate’s promotion to the England senior side came after stints as the nation’s under-21 coach and the Football Association’s head of elite development

The memes were merciless.

Southgate sits in a bath, lifejacket fastened to his torso amid the suds. He pedals away on a stationary exercise bike, helmet strapped securely to his head. His Nando’s order – plain chicken burger, straight chips, corn cob – comes bland and beige.

As England advanced through the early stages of Euro 2024 with all the elegance of a fatberg sliding down the sewer, relations became strained.

For his critics, Southgate’s team had become a caricature of the manager himself – all caution and consideration, no cut and thrust.

They saw the joy micromanaged out of England’s game and an attack second-guessing itself, doubting instincts and instead shifting the ball and responsibility sideways.

And, to a point, they had a point.

Before the Euro 2024 final, nine teams had had more shots on target than England.

The Czech Republic, eliminated in the pool stages, had only one fewer.

England ended the tournament 10th for xG – an indication of the cumulative quality of the chances they have created.

The goalless draw against Slovenia – possibly the most drab of their performances – was marked by some England fans throwing beer at Southgate as he came over to thank them for their support.

“I took this job to try to improve English football, to try to give us nights like this,” he said after England had made the semi-finals.

“I can’t deny then when things get as personal as it has that does hurt.”

Southgate, though, has plenty to throw back. His consistency at major tournaments is unmatched by any other England manager.

In 2018, he took England to the World Cup semi-finals for the first time in a generation.

In 2021, he took England to the European Championships final for the first time ever. This summer, he has repeated the feat, ensuring a first major final away from home in England’s history.

For a nation that has struggled to get anywhere near the podium at World Cups and Euros to suddenly be worried about style marks when they do, seems… demanding.

The semi-final victory over the Netherlands, when Southgate’s substitutes Cole Palmer and Ollie Watkins combined for the decisive late goal, shifted that narrative and undermined the accusation that Southgate is slow to react when England lose momentum mid-match.

Palmer, again brought off the bench, scored England’s only goal in the final defeat by Spain.

But, despite reports before the final that the FA are attempting to persuade Southgate to stay, it feels like a natural break point may still have been reached; England could benefit from a different energy, Southgate would relish a different challenge.

Despite Atomic Kitten’s protests, the magic may have run its course. Southgate and England perhaps just no longer turn each other on like they once did.

Whenever he goes, Southgate will leave behind a string of shimmering campaigns that soundtracked a succession of summers.

There is a reinvigorated connection between players and public. At Euro 2016, a one-two combination of indifference and derision had left that relationship on the floor.

Internally Southgate has ensured that a team, so often fractured by cliques and club loyalties, has been unbroken through on and off-pitch upheaval.

He could have easily stood aside to let players have their say in the summer of 2020 and its wake. It would have been easy to do and easy to defend.

Instead he stood shoulder to shoulder with them.

“This is a special group. Humble, proud and liberated in being their true selves,” he said., external

“I have never believed that we should just stick to football.

“I know my voice carries weight, not because of who I am but because of the position that I hold. I have a responsibility to the wider community to use my voice, and so do the players.”

Above all he had led his country with understated decency, sincerity and humanity – quiet qualities whose value will rise rapidly when absent.

None of this fills a cabinet at St George’s Park of course, but it is a legacy to weigh against any silverware.