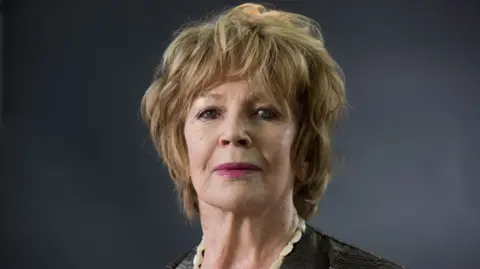

Obituary: Edna O’Brien, the controversial Irish novelist

Getty Images

Getty ImagesEdna O’Brien was the woman who scandalised Catholic Ireland.

Her book The Country Girls was banned, burned and denounced from the pulpit in her native country.

But she went on to carve a literary career and win a reputation as a controversial, ground-breaking and gifted author.

No less a literary figure as Philip Roth once described her as “the most gifted woman now writing in English”.

She was also a woman of ageless spirit who lived a colourful life to the full. In the London of the 1960s and 1970s, she had what she called a Mata Hari reputation.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesShe threw glittering parties and rubbed shoulders with stars like Marlon Brando, Elizabeth Taylor and Robert Mitchum.

But in her later life, she shrugged off the Mata Hari label as “more garbage”. She insisted it was her inner life that mattered most.

Edna O’Brien was born in December 1930 at Tuamgraney, County Clare. It was a place she later described as “fervid” and “enclosed”.

She was the youngest of four children and she grew up in rural Ireland in a strictly religious, farming family.

Lonely child

She once said that her mother, Lena – a controlling woman – did not want her to be a writer.

When asked what O’Brien was like as a child, Lena replied: “She was a very lonely child and hard to reach.”

In recent years, O’Brien said that most writers were lonely: “You would not go through the purgatorial of writing unless you were a lonely person.”

She was educated by the Sisters of Mercy, an order whose strict and often abusive style would be castigated in later years by an Irish government inquiry.

O’Brien’s first novel, The Country Girls, was published in 1960, the story of two convent school girls, Cathleen and Baba, who get expelled for writing a dirty note.

It laid bare an Ireland where young girls could be spirited, sexual beings.

O’Brien said the book was dedicated to her mother but that she did not read it.

“She thought it was courting sin… but she kind of forgave me as she got older,” she said.

“There was a lot of commotion. There were loads of people who wanted to lynch me… they thought they were in the book.”

The Country Girls was the first in a trilogy – followed by The Lonely Girl (later published as The Girl with Green Eyes) and Girls in their Married Bliss, tracing the two characters as they grow up, rebel and run away to Dublin and London.

O’Brien herself “ran away” when in 1954, against her parents’ wishes, she eloped and married the Czech-Irish writer Ernest Gebler. The couple left Ireland for London.

PA

PAThey had two sons, Carlo and Sasha, but the marriage failed after 10 years and she fought and won custody of her children.

Looking back on that period, O’Brien said that when she gave her husband The Country Girls he said: “You can write and I will never forgive you.”

“It took the ground from under his feet and his own confidence,” she said.

The novel created a scandal and was a critical and popular hit.

There was plenty of mud-slinging – although O’Brien was no stranger to insults.

John Broderick, in the literary periodical Hibernia, “quoting my husband’s exact words … said that my ‘talent resided in my knickers’.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut she went on to carve a long literary career of more than 50 years, writing novels and short stories, winning plaudits and prizes.

She was a regular presence on TV and radio. In 1979, she took part in the first edition of Question Time – alongside the MPs Teddy Taylor and Michael Foot. She was the last surviving member of that panel.

Several of her books have been adapted for stage and screen. The Country Girls took three weeks to write, but her memoir, The Country Girl, published in 2012, took as many years.

Ireland’s shame

O’Brien had a long and fraught relationship with Ireland. Among the topics she chose to write about were the Troubles, the IRA and abortion.

“Ours indeed was a land of shame,” she wrote, “a land of murder, and a land of strange, throttled, sacrificial women”.

Her novel Down by the River dealt with the true story of the X case in Ireland when a court ruled that a teenager who had been raped could not travel to the United Kingdom for an abortion.

She was heavily criticised for her treatment of this case and many did not like the lyricism of her writing.

‘I’m nobody’s groupie’

She was also lambasted for a profile of Sinn Féin president Gerry Adams that she wrote for the New York Times in 1994.

“I was asked, ‘Am I a groupie?’ I’m nobody’s groupie,” she said.

Edward Pearce, writing in the Guardian in the same year, called her “the Barbara Cartland of long-distance republicanism”.

She continued to write well into her old age, saying that she would die if she could not do so. In 2018, O’Brien was made an honorary Dame of the British Empire.

She will be remembered as a woman who changed the nature of Irish fiction.

In the words of her fellow novellist, Andrew O’Hagan, “she brought the woman’s experience, and sex and internal lives of those people on to the page, and she did it with style, and she made those concerns international”.

As a long-term exile from her native land, she had, nevertheless, Ireland to thank for her imagination and her gift.

It was one born of a childhood in the beauty and isolation of her mother country.

Without it, she said, “I wouldn’t have got the raw stuff. And the raw stuff is very good for the real stuff.”