Complex life on Earth may be much older than thought

Abderrazzak El Albani

Abderrazzak El AlbaniA group of scientists say they have found new evidence to back up their theory that complex life on Earth may have begun 1.5 billion years earlier than thought.

The team, working in Gabon, say they discovered evidence deep within rocks showing environmental conditions for animal life 2.1 billion years ago.

But they say the organisms were restricted to an inland sea, did not spread globally and eventually died out.

The ideas are a big departure from conventional thinking and not all scientists agree.

Most experts believe animal life began around 635 million years ago.

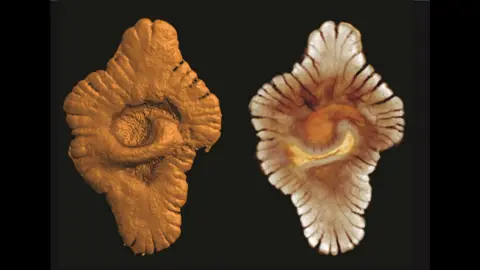

The research adds to an ongoing debate over whether so-far unexplained formations found in Franceville, Gabon are actually fossils or not.

The scientists looked at the rock around the formations to see if they showed evidence of containing nutrients like oxygen and phosphorus that could have supported life.

Professor Ernest Chi Fru at Cardiff University worked with an international team of scientists.

He told BBC News that, if his theory is correct, these life forms would have been similar to slime mould – a brainless single-cell organism that reproduces with spores.

But Professor Graham Shields at University College London, who was not involved in the research, says he had some reservations.

“I’m not against the idea that there were higher nutrients 2.1 billion years ago but I’m not convinced that this could lead to diversification to form complex life,” he said, suggesting more evidence was needed.

Prof Chi Fru said his work helped prove ideas about the processes that create life on Earth.

“We’re saying, look, there’s fossils here, there’s oxygen, it’s stimulated the appearance of the first complex living organisms,” he said.

“We see the same process as in the Cambrian period, 635 million years ago – it helps back that up. It helps us understand ultimately where we have all come from,” he added.

Abderrazzak El Albani

Abderrazzak El AlbaniThe first hint that complex life could have begun earlier than previously thought came about 10 years ago with the discovery of something called the Francevillian formation.

Prof Chi Fru and his colleagues said the formation was made up of fossils which pointed to evidence of life that could “wiggle” and move of its own accord.

The findings were not accepted by all scientists.

To find more evidence for their theories, Prof Chi Fru and his team have now analysed sediment cores drilled from the rock in Gabon.

The chemistry of the rock showed evidence that a “laboratory” for life was created just before the formation appeared.

They believe that the high levels of oxygen and phosphorus were made by two continental plates colliding under water, creating volcanic activity.

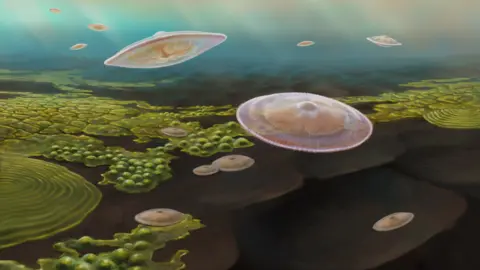

The collision cut off a section of water from the oceans, creating a “nutrient-rich shallow marine inland sea.”

Prof Chi Fru says this protected environment had the conditions to allow photosynthesis, leading to significant amounts of oxygen in the water.

“This would have provided sufficient energy to promote increases in body size and greater complex behaviour observed in primitive, simple animal-like life forms such as those found in the fossils from this period,” he said.

But he says that the isolated environment also led to the demise of the life forms because there were not enough new nutrients fed in to sustain a food supply.

PhD student Elias Rugen at the Natural History Museum, who was not involved in the research, agreed with some of the findings, saying it’s clear that “oceanic carbon, nitrogen, iron and phosphorus cycles were all doing something a little bit unprecedented at this point in Earth’s history.”

“There’s nothing to say that complex biological life couldn’t have emerged and thrived as far back as 2 billion years ago,” he said, but added that more evidence was needed to support the theories.

The findings are published in the scientific journal Precambrian Research.