Juror swears oath on river in legal first

Getty Images

Getty Images“Nature, thou art my goddess”.

Paul Powlesland was not far off quoting Shakespeare when he became probably the first juror in history to swear a legal oath on a river.

Jurors are either required to make a secular promise to tell the truth or to swear on a holy book when they attend court.

Instead the lawyer and activist produced a vial of water taken from the River Roding, at Snaresbrook Crown Court in east London.

He was met with a “quizzical” look from the court usher, who asked him to do a sip test to ensure it was not a toxic substance.

“The judge called me in and said he’d never had a request like this before – he wasn’t hostile at all, intrigued if anything,” he told the BBC.

Mr Powlesland explained that his devotion for the river, which includes planting trees along its banks, removing litter and campaigning against water pollution, is like a religion.

“I told him the river was effectively my god, and that I hold the river to be sacred”.

On this basis, the judge allowed the oath alongside a secular affirmation.

“Although I love my river I don’t know what Thames Water have been doing to it recently.”

The 38-year-old lives on a boat on the Roding, the third-largest river in London. He is the founder of the River Roding Trust, a charity that works to clean and preserve the river.

He is also the co-founder of Lawyers for Nature, a group that advocates for legal representation for elements of the natural world.

“It’s really to try and reimagine the relationship between nature and the law, and for me it’s a powerful thing to bring a piece of that nature into the courtroom.”

Getty Images

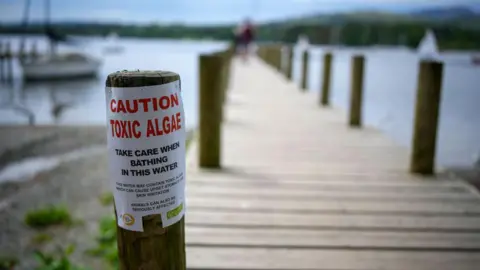

Getty ImagesEarlier this year the BBC revealed nine major English water companies have reported data suggesting they have discharged raw sewage when the weather is dry – a practice which is potentially illegal.

“Rivers have no legal representation – we increasingly have situations where environmental laws don’t protect rivers”, Mr Powlesland said.

He said he hopes his oath encourages more people to consider the environment when acting as a juror, and in their day-to-day lives.

“I fundamentally believe that until we take small steps to regard nature as sacred again, rather than a human commodity, the situation is not going to change”.

After delivering a verdict in the case on Friday, Judge Charles Falk told the jury:

“You tried this case faithfully according to the evidence, as you took an oath to do, whether on a river or otherwise.”