Violent Southport protests reveal organising tactics of the far-right

Getty Images

Getty ImagesTwo nights of violent protest in English towns this week, following the knife attack in Southport, reveal how today’s far right is organising in the UK.

A BBC analysis of activity on mainstream social media and in smaller public groups shows a clear pattern of influencers driving a message for people to gather for protests, but there is no single organising force at work.

Not everyone attending these protests or posting about the Southport attacks holds fringe views, supports rioting or has links to far-right groups. The protests also appeared to draw in people concerned about violent crime or misled by the misinformation that the attack was linked to illegal immigration.

So how did the protests – starting in Southport and spreading to London, Hartlepool, Manchester and Aldershot – begin?

Merseyside Police have publicly identified the English Defence League (EDL) as a key factor.

While there are people who describe themselves as EDL supporters, the organisation ceased to exist in any formal sense after its founder, Stephen Yaxley-Lennon – who uses the alias Tommy Robinson – focused on spreading his message on social media platforms, where he has a sizeable following.

But its core ideas – in particular an opposition to illegal immigration, mixed with indiscriminate and racist claims about Muslims – are very much alive, and loudly and widely spread among sympathisers online.

Thrown into this mix are tropes from conspiracy theories that “elites” are somehow covering up the truth – including the abuse of British children.

An influencer on X associated with Yaxley-Lennon, who posts under the name of “Lord Simon”, was among the first to publicly call for nationwide protests. His account promoted false claims that the alleged Southport attacker had been an asylum seeker, recently arrived in the UK by boat. His video has been viewed over a million times.

“We have to hit the streets. We have to make a huge impact all around the country. Every city needs to go up everywhere,” he said.

PA Media

PA MediaBBC Verify has analysed hundreds of posts on social media and in smaller public Telegram groups to get a sense of the motives of the main actors involved in organising, encouraging and attending these protests, as well as those involved in acts of violence.

It is not possible to pinpoint who started the calls for protests but there was a clear pattern – multiple influencers within different circles amplified false claims about the identity of the attacker.

These claims then travelled across social media platforms, reaching a large audience – including ordinary people without any connection to far-right individuals and groups.

“There’s not been a single driving force,” says Joe Mulhall, head of research at anti-racism research group Hope Not Hate.

“That reflects the nature of the contemporary far right. There are large numbers of people engaging in activity online but there’s no membership structure or badge – there are not even formalised leaders, but they are directed by social media influencers. It’s like a school of fish rather than traditional organisation.”

One of the earliest signs that protests were brewing came in a Southport-themed group, which was set up on Telegram about six hours after the attack.

Telegram – a messaging app which also has channels for publicly broadcasting posts – has historically been used by far-right activists who, until recently, struggled to avoid being banned on the Twitter/X platform.

It became flooded with misinformation about the identity of the alleged attacker and posts by other far-right groups such as the National Front. Users also called for a protest on St Luke’s Street in Southport, where the local mosque is, on Tuesday evening.

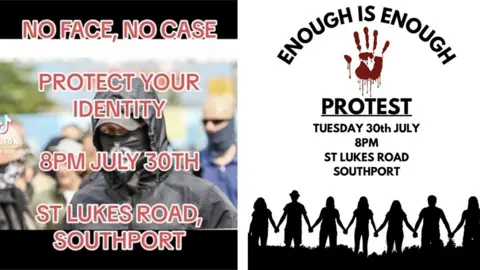

Several online graphics promoting the protest were shared on the Telegram channel. Although neither the channel nor its associated chat have many followers, those posters later migrated to TikTok, X and Facebook, where they were shared widely.

“No face, no case, protect your identity,” read one. Another poster called for “mass deportations”.

On TikTok, a now-deleted account urged demonstrators to head to Southport, advising them to hide their identities from the police.

The account used material that echoed anti-immigrant protests last year in nearby Kirkby, suggesting a local organiser.

How did the idea of protest go on to spread nationwide?

What seems to have happened is that far-right activists beyond Merseyside spotted an opportunity from the Southport tragedy to amplify their own messages on major social media platforms.

Matthew Hankinson was released from prison last year after serving six years for membership of National Action, a neo-Nazi group that was banned as a terrorist organisation in 2016.

He said on X he was “documenting live” from the Southport demonstration with videos – and the time stamps match up to when clashes were taking place. He described the scenes as “police oppression of peaceful protesters concerned about the murder of white children” – and one of his videos has been viewed more than 8,000 times.

Hankinson also uses his account to justify extreme violence, post racist material, and quote the neo-Nazi who murdered the Labour MP Jo Cox.

“I went to Southport with the intention of attending the vigil to show solidarity with the people and pay my condolences in a private capacity,” he told the BBC, adding that he began filming when he saw the clashes between police and protestors.

Far more significant has been Yaxley-Lennon. He left the UK on Sunday night ahead of a major court hearing that could have seen him taken into custody.

Reuters

ReutersHe has been rebuilding his profile since his X account was restored last year – and now has 800,000 followers.

His posts on the tragedy in Southport, and the related disorder, have regularly been shared or liked thousands of times.

He has accused the police of spreading lies and has claimed: “The government and ‘authorities’ created this.”

BBC Verify identified two of his prominent supporters in video footage of Southport protests: Rikki Doolan and Jesse Clarke, who last week had appeared on stage at a demonstration for Yaxley-Lennon.

Mr Doolan, a self-styled preacher, recorded a video of himself at the protest in Southport saying: “I’m British and proud, otherwise I wouldn’t be here.”

On Wednesday, Mr Clarke posted videos of the protests in central London outside the prime minister’s home, saying: “We’re outside Downing Street now.”

Followers of smaller groups, including Patriotic Alternative, which organised anti-immigrant demonstrations, have also been promoting the Southport attack protests. They may not have the reach, but their slogan “Enough is Enough” has been widely shared with almost 60,000 mentions on X alone since Monday 29 July, according to the Brandwatch social media analysis tool.

“The language is coming from far-right individuals but the organisation is much more organic,” says Mr Mulhall from Hope Not Hate.

“There are local Facebook groups emerging. They take the lead from the influencers and pass the information about locally. The weather is made on Twitter, but the organising happens elsewhere.”

What happens next is difficult to predict.

The BBC has identified at least 30 additional demonstrations being planned by far-right activists around the UK, including a new protest in Southport – but it is unclear how much traction any will have.

Some of the social media posts relating to the plans are directly referencing the Southport attack and “Enough is Enough”. Others are more general in nature – focusing on fears of illegal migration or the need to protect children.

BBC Verify reporting team: Paul Brown, Kayleen Devlin, Paul Myers, Emma Pengelly, Olga Robinson and Shayan Sardarizadeh. Additional reporting by Daniel De Simone.