Riots resurface memories of racist violence for British Asians – with glimmer of hope

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMosques attacked with bricks and stones. Marchers chanting “we want our country back.” And a man’s head reportedly stamped on during a racist attack.

These scenes from the past week in England and Northern Ireland have sparked painful memories among British Asians who remember the 1970s and 80s, when racist violence was widespread and the National Front was on the rise.

Harish Patel, in his 70s, says it broke his heart.

He says teenagers will have heard from their parents and grandparents about what life could be like in this country.

“They’ll have thought it was all over. And now they are experiencing it for themselves.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe disorder was triggered by the fatal stabbing of three young girls in Southport – followed by false speculation that the suspect was a Muslim asylum seeker.

It sent a thunderbolt of fear down Asian and minority communities.

Mungra, an elderly Asian woman who arrived from Kenya 50 years ago, was taken back to her early days in London.

She worried the escalating violence would make it too frightening to get milk from the corner shop. “That’s how we felt in those days, and I worry.”

Tens of thousands of South Asians came to work in the the UK’s factories and public services in the 1950s, as the country rebuilt its post-war economy.

By the early 1970s, the population had grown to around half a million – because of family reunions and Asians fleeing East Africa, many of whom had been expelled from Uganda.

Immigration became a politically charged issue. In 1968, Conservative MP Enoch Powell had given his explosive “rivers of blood” speech, in which he said that by permitting mass immigration, the country was “heaping up its own funeral pyre”.

The extreme right-wing National Front was at its most vocal and regularly held rallies. Asians had to contend with day-to-day harassment and police brutality.

“The climate and fear of racism was so profound that it was hard to ignore that I was of coloured skin,” Mungra says.

“It was the usual name-calling when walking on the street, the p-word.“

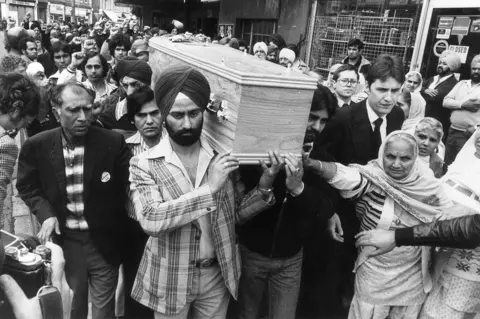

Mungra witnessed the riots in Southall, a predominantly Asian part of west London. They took place in 1979, three years after the racist murder of local Sikh teenager Gurdip Singh Chaggar.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWeeks before a general election, the National Front decided to hold a meeting in Southall’s town hall.

Thousands – mainly Asians, but also anti-racist allies – took to the streets in protest against the far-right and police brutality.

Forty were injured, including 21 police, 300 were arrested and a teacher was killed, probably by an officer who struck a fatal blow, according to a Met Police report.

These were brutal times which left a lasting trauma on those who lived through them. And they bring me back to my own childhood.

I was only a toddler when a lit firework was put through the letterbox of my parents’ home in Hampshire. Our neighbours didn’t like Asians living on the street.

My mum recalls grabbing my brother – a hyperactive child a few years older than me – as he ran towards the front door.

She was shaking for hours afterwards. She’ll never forget how frightened she felt in that moment.

It happened months after the p-word was scrawled on our garage door. We were living with my Gujarati sari-wearing grandmother at the time, and my parents felt incredibly vulnerable.

They felt they were being targeted for looking different when all they were doing was trying to live a happy life in 1980s Britain. We moved shortly afterwards.

It’s striking that decades later, I’ve heard Asians – including members of my own family – saying they were again scared to leave their homes.

Nervously tugging his fingers, Iqbal, a father from Bolton in his 50s, told me he was terrified and that his children had told him to not go outside.

“I thought these days of race hatred were over,” he said.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOver the seven days of riots, hotels housing asylum seekers were attacked, minority-owned businesses were looted and cars and buildings set alight. More than 400 arrests were made.

Muslims were particularly targeted – with missiles hurled at mosques, Islamophobic chants and Muslim gravestones in Burnley vandalised.

Police patrols were ramped up, but some younger people said they didn’t trust officers to protect them.

“We don’t feel like they’ve got our back when they haven’t protected us so far. We feel vulnerable and feel like we’ve got to protect ourselves,” said Mohammad, in his 20s.

But Wednesday felt like a turning point.

As communities braced for a night of disorder, after names and addresses of immigration lawyers were spread online, the unrest largely failed to materialise.

Instead, thousands of anti-racism protesters rallied in cities and towns across England. People chanted “racism off our streets”.

In Accrington, Lancashire, Muslim anti-fascist protesters who went to protect a local mosque were embraced by pubgoers, in a “massive” moment of unity.

Getty Images

Getty Images“There were a few shouts of ‘respect’ which was fantastic; we need to see unity to stop all this far-right violence,” said Haddi Malik, who was in the group.

The show of force has offered people a moment of hope and courage, and a sense of relief.

But the ripples of intimidation haven’t yet settled. Some have been left wondering whether they’re really accepted in this country.

“I don’t want to be made to feel like that,” says 20-year-old Muslim Hamza Moriss. “I’m a part of this country as much as they are.”

Meanwhile, Mungra feels a deep sense of unease.

“The last week has made me think that not much has really changed, that racism is still very much alive and we won’t ever actually be seen as the same… not really.”

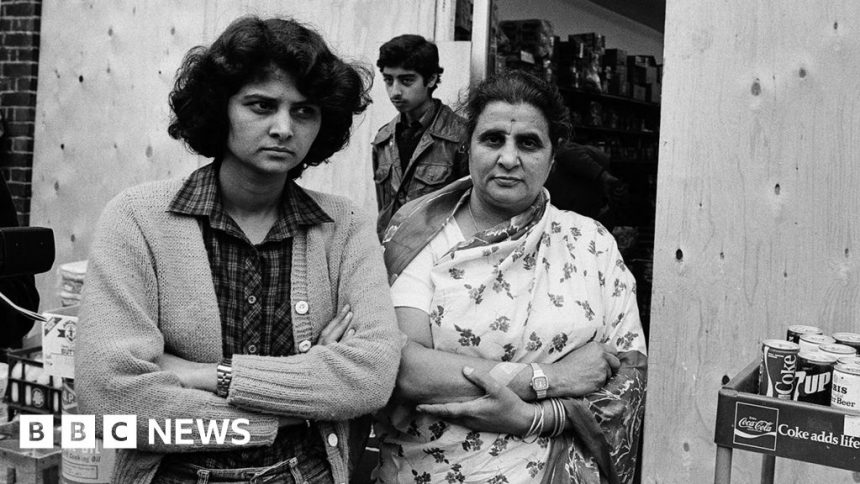

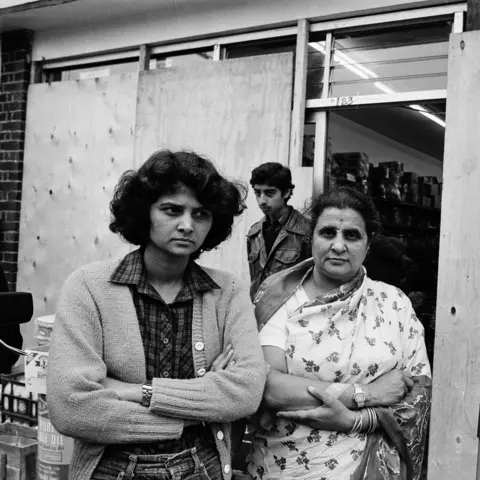

Top image shows a damaged shop on The Broadway in Southall following rioting in the area, taken on 4 July 1981.