Why Scotland may have avoided far-right unrest

PA Media

PA MediaFor more than a week, far-right violence has been flaring up in cities in England and Northern Ireland – but not so far in Scotland.

It begs the question, are we immune north of the border?

The violence began after the murders of three girls in Southport in Merseyside. Posts online erroneously suggested the attacker was Muslim and an asylum seeker.

Mosques have been targeted, police officers hurt and businesses torched – including hotels known to house asylum seekers.

Historian Prof Murray Pittock is wary of the term “Scottish exceptionalism”. This is a phrase used to describe a particular attitude, a sense of moral superiority – that things are different here; that views and attitudes are much more liberal and forward-thinking.

But he does say that attitudes in Scotland towards immigration are more favourable.

“I think there’s a balance here. You don’t want to be going down the route that Scotland’s exceptional, saying: ‘We will never do things like this’. Nor do you want to go down the route of saying: ‘Actually, it’s just the same as the rest of the UK’. It’s clearly not.

“There hasn’t been a large-scale, enabling narrative which has been condemnatory of immigration.

“There’s been pro-immigrant rhetoric and that’s increasingly borne out in the Scottish Social Attitudes Survey, which is more pro-immigrant. It’s now more pro-immigrant than south of the border.”

Scotland is not the only part of the UK to avoid the disorder – Wales has also managed to stay clear of the ugliest scenes witnessed since the tragic events in Southport.

Much of the trouble has been incited – and indeed organised – through social media, inflamed by negative and often racist sentiments about immigration.

The very first rally in Southport had been discussed on anti-immigration channels on the Telegram messaging app. Police said the violence was believed to have involved supporters of the now disbanded far-right group the English Defence League (EDL).

The EDL’s founder, convicted criminal Tommy Robinson (real name Stephen Yaxley-Lennon), has also been posting about “pro-UK” rallies in cities including Glasgow next month, saying “the British are rising”.

But both in Scotland and Wales, rumoured far-right protests have so far failed to materialise. When hundreds gathered for an anti-racism rally in Glasgow on Saturday, only two counter-protesters turned up.

PA Media

PA MediaJournalist Lizzie Dearden, who commentates on home affairs issues and is an expert on the far-right in the UK, says Southport is not the first incident that has been used to fuel far-right agendas.

If anything, she says, it is part of a long-running pattern whereby there has been a “frenzy of activity” after terror attacks among the far-right, who seek to “present the different minority groups as a threat”.

In Scotland, though, she says the far-right has to work harder to convince people of this.

“I think there are still people who are active in these networks in Scotland and they are likely to try to capitalise on this terrible attack in Southport as they did in England,” she says.

“Polling and other kinds of measures show that Scotland has a more positive attitude towards migration, a lower concern about things like small boats – which are naturally more geographically keenly felt on the southern coast of England – and a more positive attitude towards refugees.”

As for planned events in Scotland, Ms Dearden says it is still possible there could be some form of protest – but that it would be “fairly small”.

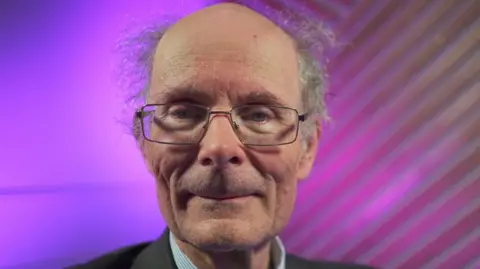

Prof Sir John Curtice, who keeps a close eye on the barometer of public attitudes, agrees – but says the idea of Scotland as “a wholly welcoming nation” is “too rosy a picture”.

Although Scots are less likely to be concerned about immigration, he says a key issue is that campaigns that focus on “Britishness” do not have the same resonance in Scotland.

“For many people, their principle sense of identity is Scottishness,” he says.

Sir John says population plays a part too, with the proportion of people identifying as Muslim in Scotland much smaller than in England.

The latest Scottish census shows 7% of the population is from an ethnic minority, compared to 18% overall in the UK.

Sir John also says the message of the party in government is very different in Scotland. The SNP is described as a “civic nationalist party”, which says it welcomes people irrespective of birth or ancestry as long as they are willing to commit themselves to Scotland.

He adds: “It’s also the case that attitudes to immigration, particularly among politicians, is also different because Scotland faces a particularly difficult demographic timebomb – there are more politicians who are likely to argue that Scotland needs immigration.”

Of course, this comes just as former First Minister Humza Yousaf publicly questioned whether he sees a life for himself and his family in Scotland, or in the West, in the wake of the riots.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesUnsurprisingly, the police shy away from being too specific about why nothing has happened in Scotland so far.

Assistant Chief Constable Gary Ritchie says it is difficult to put his finger on one particular reason why the unrest has not spread to Scotland.

“I think we have done an awful lot of very strong community engagement over the previous months and years and built really strong relationships with all our communities,” he says.

“We’re not complacent, we don’t think we’re immune, which is why we’re keeping a close eye and making sure our communities remain peaceful for the days ahead.”

Even in recent years, Glasgow has seen its fair share of unrest.

In June 2020, violence erupted in George Square after National Defence League supporters gathered to “protect the Cenotaph”. This came at the time of widespread demonstrations in support of the Black Lives Matter movement.

The following year a very different sort of protest took place on Kenmure Street in the southside, as local residents blocked the deportation of two Indian immigrants.

It paints a picture of divided politics in Glasgow.

Football rivalry

Prof Pittock says the largest bouts of civil unrest in his lifetime in Scotland have been associated with the long-standing rivalry between Celtic and Rangers.

He says there is an “inherited fault line” on Irish immigration, Irish Catholicism and Scottish Protestantism in the west coast, which goes back to the 19th Century.

“In various manifestations, that has actually created more public disorder than any other issue,” he says.

“The fault lines are different and where the fault lines are different you probably shouldn’t expect the same kinds of behaviour in the same way.”

There’s one other key and very Scottish difference that Prof Pittock notes: “Without being absolutely banal, in Scotland the weather is worse and there is less opportunity for public unrest.”

First Minister John Swinney says Scotland will remain vigilant following a meeting with Police Scotland and party leaders.

But the temperature across the UK has arguably changed as the week has progressed.

Swift action by the police and courts south of the border has led to more than 700 arrests and over 300 charged. Some have already received some hefty jail terms.

One man, charged in connection with attacks on a Holiday Inn Express near Rotherham which was housing asylum seekers, began to cry as he was led from court.

And thousands took to the streets for peaceful rallies in towns and cities across England on Wednesday evening. Met Police chief Mark Rowley called it a “very successful night”, saying the fears of extreme-right disorder were “abated”.

Riot squads remain on alert this weekend – but with peaceful anti-racism protests currently outnumbering cases of disorder, police commanders are hopeful it will remain peaceful.