‘My family died in front of my eyes’: Harrowing tales from a Myanmar massacre

BBC/Aamir Peerzada

BBC/Aamir PeerzadaWarning: This article contains details some readers may find distressing.

Fayaz and his wife believed they were moments from safety when the bombs began to fall: “We were getting on the boat one after another – that’s when they started bombing us.”

Wails and shouts filled the air around 17:00 local time on 5 August, Fayaz* says, as thousands of scared Rohingyas made their way to the banks of the Naf river in the town of Maungdaw.

Attacks on villages earlier in the area meant this was what hundreds of families, including Fayaz’s, saw as their only option – that to get to safety, they had to escape from western Myanmar to Bangladesh’s safer shores.

Fayaz was carrying bags stuffed with whatever they had managed to grab. His wife was carrying their six-year-old daughter, their eldest was running alongside them. His wife’s sister was walking ahead, with the couple’s eight-month-old son in her arms.

The first bomb killed his sister-in-law instantly. The baby was badly injured – but alive.

“I ran and carried him… But he died while we were waiting for the bombing to stop.”

Nisar* had also made it to the riverbank by about 17:00, having decided to escape with his mother, wife, son, daughter and sister. “We heard drones overhead and then the loud sound of an explosion,” he recalls. “We were all thrown to the ground. They dropped bombs on us using drones.”

Nisar was the only one of his family to survive.

Fayaz, his wife and daughter escaped and would eventually make it across the river. Despite his pleas, the boatman refused to allow Fayaz to bring the baby’s body with them. “He said there was no point in carrying the dead, so I dug a hole by the river bank and hastily buried him.”

Now they’re all in the relative safety of Bangladesh, but if they are caught by authorities here they could be sent back. Nisar clutches a Quran, unable still to process how his world was shattered in a single day.

“If I’d known what would happen, I would never have tried to leave that day,” Nisar says.

It is notoriously difficult to piece together what is happening in Myanmar’s civil war. But the BBC has managed to construct a picture of what happened on the evening of 5 August through a series of exclusive interviews with more than a dozen Rohingya survivors who escaped to Bangladesh, and the videos they shared.

All of the survivors – unarmed Rohingya civilians – recount hearing many bombs exploding over a period of two hours. While most described the bombs being dropped by drones, a weapon increasingly being used in Myanmar, some said they were hit by mortars and gunfire. The MSF clinic operating in Bangladesh has said it saw a big surge in wounded Rohingya in the days that followed – half of the injured were women and children.

Survivors’ videos analysed by BBC Verify show the river bank covered in bloodied bodies, many of them women and children. There’s no verified count of the number of people killed, but multiple eyewitnesses have told the BBC they saw scores of bodies.

Survivors told us they were attacked by the Arakan Army, one of the strongest insurgent groups in Myanmar which in recent months has driven the military out of nearly all of Rakhine State. They said they were first attacked in their villages, forcing them to flee, and then were attacked again by the river bank as they sought to escape.

The AA declined to be interviewed but its spokesman Khaing Tukha denied the accusation and responded to the BBC’s questions with a statement which said “the incident did not occur in areas controlled by us”. He also accused Rohingya activists of staging the massacre and falsely accusing the AA.

Nisar stands by his account, however.

“The Arakan Army are lying,” he says. “The attacks were done by them. It was only them in our area on that day. And they have been attacking us for weeks. They don’t want to leave any Muslim alive.”

Most of Myanmar’s Rohingya Muslims live as a minority in Rakhine – a Buddhist-majority state, where the two communities have long had a fraught relationship. In 2017, when the Myanmar military killed thousands of Rohingyas in what the UN described as “a textbook example of ethnic cleansing”, local Rakhine men also joined the attacks. Now, amid a spiralling conflict between the junta and the AA, which has strong support in the ethnic Rakhine population, Rohingyas once again find themselves trapped.

Handout

HandoutDespite the risk of being caught and returned to Myanmar by the Bangladeshi authorities, Rohingya survivors told the BBC they wished to share details of the violence they faced so it would not go undocumented, especially as it unfolded in an area that is no longer accessible to rights groups or journalists.

“My heart is broken. Now, I’ve lost everything. I don’t know why I survived,” Nisar says.

A wealthy Rohingya trader, he sold his land and house as the shelling increased near his home in Rakhine. But the conflict intensified faster than he expected, and on the morning of 5 August, the family decided to leave Myanmar.

He is crying as he points to his daughter’s body in one of the videos: “My daughter died in my arms saying Allah’s name. She looks so peaceful, like she’s sleeping. She loved me so much.”

In the same video, he also points to his wife and sister, both severely injured but alive when the video was filmed. He could not carry them out as bombs were still falling, so he made the agonising choice to leave them behind. He found out later they had died.

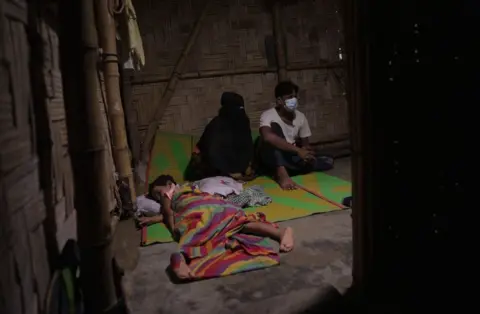

BBC/Aamir Peerzada

BBC/Aamir Peerzada“There was nowhere left that was safe, so we ran to the river to cross over to Bangladesh,” Fayaz says. The gunfire and bombs had followed them from village to village, and so Fayaz gave all his money to a boatman to carry them across the river.

Devastated and angry, he holds up a photo of his son’s bloodied body.

“If the Arakan Army didn’t fire at us, then who did?” he asks. “The direction that the bombs came from, I know the Arakan Army was there. Or was it thunder falling from the sky?”

These accusations raise serious questions about the Arakan Army, which describes itself as a revolutionary movement representing all the people of Rakhine.

Since late last year, the AA, part of the larger Three Brotherhood Alliance of armed insurgents in Myanmar, has made huge gains against the military.

But the army’s losses have brought new dangers for Rohingyas, who have previously told the BBC they were being forcibly recruited by the junta to fight the AA.

This, together with the decision by the Rohingya militant group ARSA to ally itself with the junta against the Rakhine insurgents, has soured already poor relations between the two communities and left Rohingya civilians vulnerable to retribution.

One survivor of the 5 August attack told the BBC that ARSA militants who had aligned themselves with the junta had been among the fleeing crowd – and that might have provoked the attack.

“Even if there was any military target, there was a disproportionate use of force. There were children, women, the elderly that were killed that day. It was also indiscriminate,” says John Quinley, a director of the human rights group Fortify Rights, which has been investigating the incident.

“So that would leave us to believe that there are reasonable grounds to believe that a war crime did happen on 5 August. The Arakan Army should be investigated for these crimes and Arakan Army senior commanders should be held accountable.”

This is a precarious moment for the Rohingya community. More than a million of them fled to Bangladesh in 2017, where they continue to be restricted to densely-packed, squalid camps.

More have been arriving in recent months as the war in Rakhine reaches them but, it’s no longer 2017, when Bangladesh opened its borders. This time, the government has said it cannot allow any more Rohingyas into the country.

So survivors who can find the money to pay boatmen and traffickers – the BBC was told it costs 600,000 Burmese kyat ($184; £141) per person – then have to slip past Bangladeshi border guards and chance their luck with locals, or hide in Rohingya camps.

When Fayaz and his family arrived in Bangladesh on the 6 August, the border guards gave them a meal but then put them on a boat and sent them back.

“We spent two days afloat with no food or water,” he says. “I gave my daughters water from the river to drink, and pleaded with some of the others on the boat to give them a few biscuits from the packets they had.”

They got into Bangladesh on their second attempt. But at least two boats have capsized because of overcrowding. One woman, a widow with 10 children, said she had managed to hide her family during the bombing, but five of her children drowned when their boat overturned.

“My children were like pieces of my heart. When I think of them, I want to die,” she says, weeping.

Her grandson, a wide-eyed eight-year-old boy, sits beside her. His parents and younger brother also died.

Handout

HandoutBut what of those who were left behind? Phone and internet networks in Maungdaw have been down for weeks but after repeated attempts, the BBC contacted one man, who wished to remain anonymous for his own safety.

“The Arakan Army has forced us out of our homes and are holding us in schools and mosques,” he said. “I am being kept with six other families in a small house.”

The Arakan Army told the BBC that it rescued 20,000 civilians from the town amid fighting against the military. It said it was providing them with food and medical treatment, and add that “these operations are conducted for the safety and security of these individuals, not as forced relocations”.

The man on the phone rejected their claims. “The Arakan Army has told us they will shoot us if we try to leave. We are running out of food and medicines. I am ill, my mother is ill. A lot of people have diarrhoea and are vomiting.”

He broke down, pleading for help: “Tens of thousands of Rohingya are under threat here. If you can, please save us.”

Across the river in Bangladesh, Nisar looks back at Myanmar. He can see the shore where his family was killed.

“I never want to go back.”

Additional reporting by Aamir Peerzada and Sanjay Ganguly

* Names have been changed on request