Nostalgic Indians flock to cinemas to watch old hits

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhen Zakia Rafiqi, 26, heard that Laila Majnu, a 2018 Bollywood film, was being re-released in cinemas this month, she knew she had to watch it again.

“In 2018, I was among a handful of people in the cinema. This time, there were many more people. A lot of them were laughing and crying,” says Ms Rafiqi, who went with her sister to a cinema in Delhi.

Ms Rafiqi says she has an “emotional connect” with the film, a tragic love story set in Indian-administered Kashmir, where she is from.

“It’s good to see a piece of home on the big screen. When they are driving through the streets of Kashmir, you feel you are there,” she says.

Laila Majnu, written by popular filmmaker Imtiaz Ali, barely made a mark at the box office when it was first released, but did good business on its second run. It is one among dozens of Indian films – some made more than two decades ago – which are getting a new lease of life as people flock to watch them on the big screen.

India’s film industry, like others across the world, has seen ups and downs since the coronavirus pandemic shuttered cinemas for months and led many to turn to streaming services. It is yet to return to its former glory.

“This year has been particularly bad for new [Bollywood] releases,” says trade analyst Komal Nahta.

The industry – dominated by Hindi-language Bollywood – is now churning out films more regularly, but it’s common to hear people say they will wait for a film to stream on Netflix or Amazon Prime Video instead of going to cinemas.

Some films do break through – Stree 2, a Hindi horror-comedy currently playing in cinemas, has earned close to four billion rupees ($47.6m; £36.1m) domestically so far to become the year’s biggest Bollywood hit. In terms of overall earnings, it is second only to Kalki 2898 AD, a “pan-Indian” film which featured some of the country’s biggest stars. But these are rare bright spots for an industry which has seen highly anticipated films with big stars fare miserably at the box office this year.

There’s no doubt that India’s film industry is continuing to see a churn as viewing habits shift – the top 10 films so far this year include three from the southern state of Kerala, where budgets are comparatively small.

- The southern Indian films winning on Bollywood’s turf

- Why Bollywood’s big films are flopping at the box office

So it’s not surprising that both film distributors and viewers are turning to the comfort of the familiar. A look at the list of films being released again shows there’s no clear formula behind the choices.

Bollywood re-releases this year are across a range of genres. The 1990s seem to be a favourite decade with much-loved rom-coms Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge and Hum Aapke Hain Koun and action thrillers Main Khiladi Tu Anari and Baazigar getting a second outing. More recent hits – musical Rockstar (2011), buddy film Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara (2011) and rom-com Jab We Met (2007) – have also brought people back to cinemas.

Analysts say the biggest surprise was the success of Laila Majnu. The film’s makers have said they were particularly happy that viewers in Kashmir could watch it as cinema halls reopened there in 2022 after more than two decades.

“The film has finally recovered its cost or at least minimised its losses,” says Mr Nahta, who adds that this will spur others to see if their films could also benefit from a re-release.

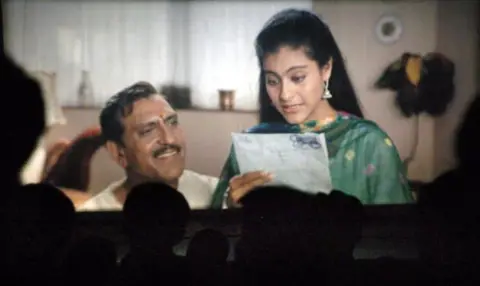

Facebook/Mohanlal

Facebook/MohanlalTaran Adarsh, a Bollywood analyst, says these re-releases are making up for a lack of new films and lacklustre box-office performances.

The re-releases have little to no promotion, with posters simply popping up on ticket booking sites or circulating on social media. “It’s driven purely by nostalgia or an audience’s love for a film that already has a cult following,” says Mr Adarsh.

In Tamil and Telugu, the re-releases have been more star-driven. Recent videos show fans of Telugu superstar Chiranjeevi dancing to a hit song from his 2002 hit Indra in cinemas. Pawan Kalyan’s Gabbar Singh (2012) is set to release next week. In Tamil, Vijay’s Ghilli (2004) ran to packed halls in April.

“It’s usually the film of a superstar whose star may have just been rising 20 years ago or a film that was already a hit,” says Sreedhar Pillai, an analyst who tracks the southern film industries. “It has to be driven by nostalgia and have a connection with an actor who is a big star today.”

Malayalam superstar Mohanlal has two such films – Devadoothan (2000) and Manichithrathazhu (1993) – currently running in cinemas in Kerala. Coincidentally, both are horror films.

Devadoothan, an eerie film with beautiful songs which flopped when it first released, has been running to packed cinemas for more than a month.

Mr Pillai says that Manichithrathazhu, a cult classic which broke box-office records when it first released, is probably the biggest “success story” among re-releases in southern India.

“It’s an iconic film. A huge blockbuster when it was released, and now it’s also getting the young audience,” he says.

Sometimes, the prospect of a sequel can drive interest in the first film.

Last year, the 2001 film Gadar: Ek Prem Katha had another successful run in cinemas after its sequel Gadar 2 became a massive hit, says Mr Nahta.

But the re-release of Kamal Haasan’s Indian this year did not see similar success because its sequel Indian 2 did not perform well, he adds.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSo why are people paying to watch older films that are easily available on streaming platforms?

“You simply can’t compare the experience of watching a film online with watching it in theatres and that is what audiences are turning out for,” Mr Adarsh says.

Shruti Zende agrees. The 30-year-old from Pune city in Maharashtra state has watched a couple of re-releases since last year.

“Instead of watching the film for its storyline, it becomes a group experience where you’re watching with people who really like the movie,” she says, adding that people start reacting before a scene or dialogue because “they know what’s coming up”.

She is now looking forward to watching Telugu superstar Nagarjuna’s 2004 film Mass on the big screen this week.

But her final verdict on re-releases will give hope to beleaguered filmmakers.

“I may watch one or two re-releases a year,” she says. “But after that I’d still want to watch a new film.”