Crumbling concrete schools will suffer ‘for years to come’

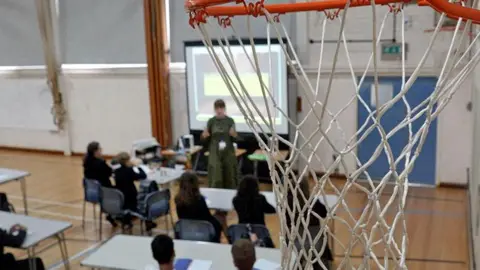

BBC / Gemma Laister

BBC / Gemma LaisterOne year ago, teachers, parents and pupils in England were preparing to head back to school as usual – until, for some, panic mode set in.

Schools were suddenly told to close any building containing Reinforced Autoclaved Aerated Concrete, or Raac – a dangerous type of material prone to collapse – that did not have safety measures in place.

Sports halls, libraries, and classrooms were taped off. Teachers had to abandon ship so quickly that in some cases, half-drunk cups of tea sat on their desks for months.

Now, as schools prepare for another year affected by Raac, a head teachers’ union is warning that many will feel the financial impact for “years to come”.

‘Hugely disadvantaged’

For affected schools, the past 12 months have involved stretches of learning from home and in temporary classrooms. Head teachers became worried about the impact on learning – with specialist spaces like science labs out of action, and the government refusing requests for special consideration in exams.

“We were in the midst of the chaos,” says Chris Hammill, head teacher at St Leonard’s Catholic School in Durham.

In the first term of last year, students took turns to come into makeshift classrooms, sometimes learning without desks in groups of more than 200 in the sports hall. Some were learning from home. Others were catching buses into school, only to jump on other buses to alternative sites, eating into the school day.

It was hardly a pretty picture for parents weighing up where they wanted their 10-year-olds to go to secondary school – and the decision of some to vote with their feet has wreaked havoc on the school’s finances.

Bishop Wilkinson Catholic Education Trust

Bishop Wilkinson Catholic Education Trust“You base your budget and your staffing levels and your curriculum on the numbers that come in,” says Mr Hammill.

St Leonard’s is usually oversubscribed for its 230-odd places, but next week only around 180 new Year 7s will come through its doors.

Schools are given money per pupil, and Mr Hammill says the drop in numbers means that, because of a lag in funding, the school will receive £300,000 less than usual in 2025/26.

“We’ve staffed the school on 230 pupils in each year group and then all of a sudden, 50 students are not coming – quite understandably – because of the the extreme situation,” he says.

As the new Year 7s make their way through secondary school, the school fears it could mean that it is £2m short. It wants the government to guarantee its income based on the number of pupils in previous year groups.

“It’s really disappointing because we’ve been hugely disadvantaged in the year that we’ve had, and then it feels like we’re going to be further disadvantaged for a number of years,” says Mr Hammill.

There are usually waiting lists for Myton School in Warwick, says head teacher Andy Perry, but this year there will be nine new form groups instead of 10.

Mr Perry says Raac will have had an impact, especially as another secondary school recently opened nearby, giving parents more choice when they were making their decisions last autumn.

“Whilst the school’s in a good place now, in the autumn term there was a huge amount of uncertainty over what Myton would look like, what the buildings would look like, how we would be able to educate the children,” he says.

“We will have a significant hit to our finances, which means we’ll have to draw our belt in and have fewer staff.”

He is disappointed because he feels that the Raac crisis was “avoidable”, but he is now happy with the temporary classrooms on site and a new building is due in the next four years.

Pepe Di’Iasio, general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, is calling on the government to offer “financial protection” to schools in this situation, as well as funding to help pupils catch up on “lost learning”.

“Even small changes in pupil numbers can have significant implications for school budgets,” he says.

“This is a problem decades in the making and something that will be to the financial detriment of the schools affected for years to come.”

‘Tightening our belts’

By February, the government had identified 234 schools and colleges in England with Raac. It placed around half of them on the School Rebuilding Programme, filling the final spots and dashing the hopes of other old schools without Raac which had applied for rebuilds.

The rest were told they would receive grant funding to remove the Raac, bar a handful that had alternative plans already.

Of 110 schools set to receive grants, 20 responded to BBC emails last month. Of those, six said all Raac had been removed, one said some Raac had been removed and 13 said no Raac had been removed.

Kim Earle, head teacher at Altrincham College, was no stranger to Raac when the guidance changed last August.

“We’d been there and got the t-shirt,” she tells the BBC. “It’s been awful.”

The concrete was first discovered just before Christmas 2019 and large parts of the school ended up needing to close, including about 10 classrooms, a special educational needs facility and the school’s drama studio.

The school is now Raac-free and hasn’t seen a drop in pupil numbers this year – although fewer students have chosen drama GCSE – but Ms Earle says she had to wait a year to be reimbursed £217,000 from the Department for Education (DfE) for the removal.

“We have had to tighten our belts,” she says, including hiring less experienced staff and cutting back on subject-specific spending, like PE equipment.

“We had to introduce a sort of bidding system for staff… if they felt there was something they really needed.”

Ms Earle says she doesn’t want any school to experience what hers has gone through, and wants others to know there is hope.

“At the end of the day you will have a safe school,” she says. “Once you are safe in the knowledge that you will have a safe school, you can get on with teaching.”

Altrincham College

Altrincham College‘Hopeful’

Every school with Raac has had a different experience, depending on the extent of the Raac, its location within the school, and the location of the school within the country.

Despite the financial complications, all three schools have had positive dealings with the DfE.

Mr Perry says his initial experience with the department was “absolutely appalling”, but that changed in late September.

“From that point, they have put a lot of money, a lot of time, a lot of resources, a lot of support in for my school and I’m very, very grateful to them,” he says.

In February, Bridget Phillipson, then Labour’s shadow education secretary, asked the DfE to publish a planned timetable for the removal of Raac from the school estate.

The following month, she said the government also needed to provide timelines to all schools in need of rebuilding work, regardless of whether or not they had Raac.

The new government has not published either timetable. The DfE said it was working closely with schools and colleges with Raac.

“We remain fully focused on work to resolve this problem as quickly as possible, permanently removing Raac either through grant funding or the school rebuilding programme,” it said.

At St Leonard’s, Mr Hammill says things are looking up. He is also pleased with new temporary learning spaces, and the school is set to have a new building by Easter 2026 – earlier than expected.

“I feel really hopeful for the future,” he says. “It’s unlike anything, how adversity brings strength.”