£30m a year – why F1 designer is one of sport’s highest-earning Britons

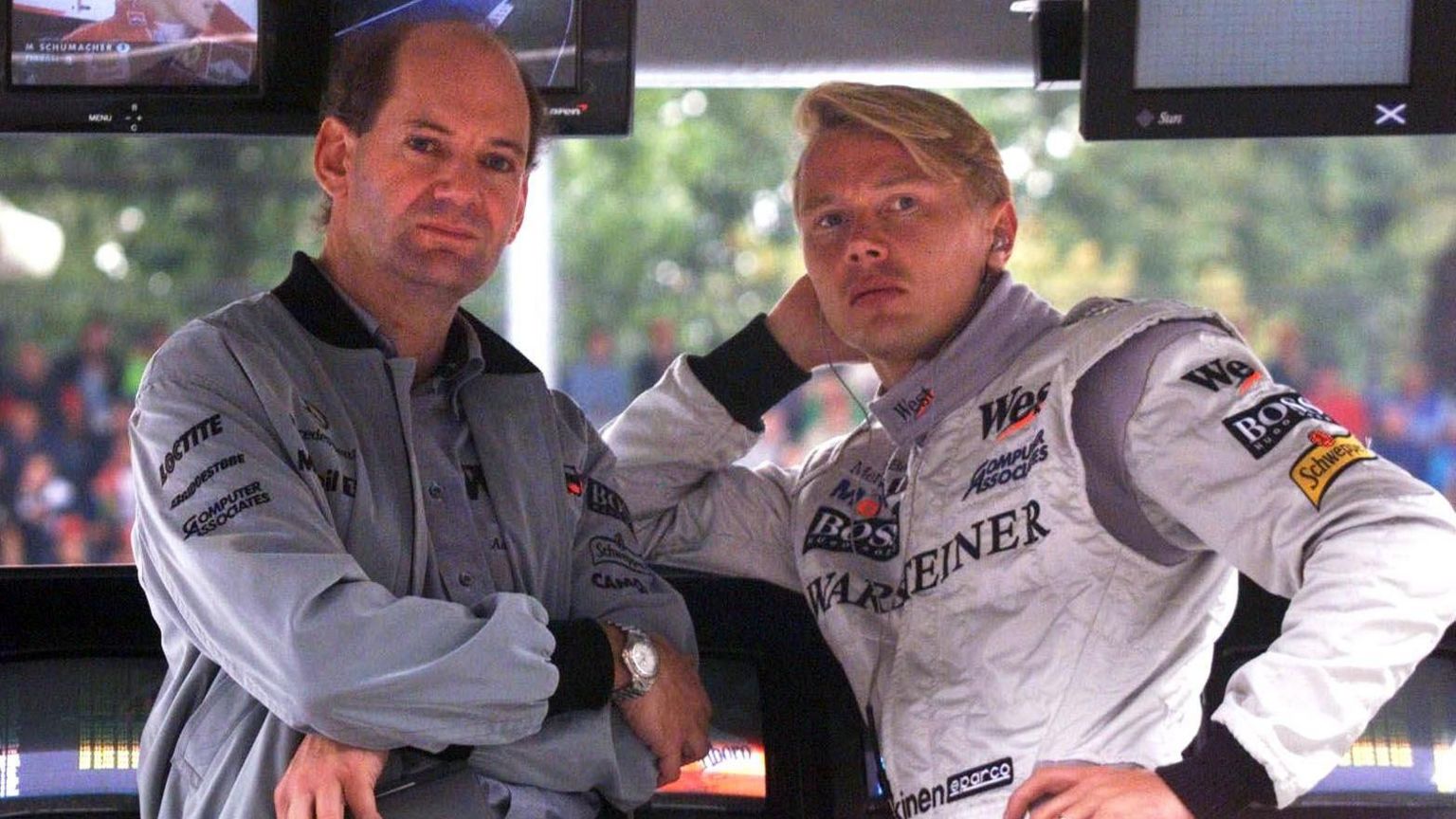

Mika Hakkinen (right) won F1 titles in 1998 and 1999 with McLaren in Adrian Newey-designed cars

-

Published

Adrian Newey is joining Aston Martin on a salary that could rise to £30m, including bonuses and add-ons. That is a lot of money for an engineer – but then Newey is not just any engineer.

That money is believed to be more than all the drivers are earning, bar Max Verstappen, Lewis Hamilton and Lando Norris. And in terms of wider British sporting figures, Newey would be behind Anthony Joshua, Rory McIlroy and Tyson Fury, according to business magazine Forbes.

It is an eye-watering number, but many would argue the 65-year-old is worth every penny.

Newey is regarded as the greatest car designer in F1 history. His statistics alone speak for themselves – 13 drivers’ championships and 12 constructors’ titles across three different teams in a F1 career which really took off from 1988.

But with Newey it is not just about the statistics. It is about what is behind them. He is a visionary, in more than one sense.

It is his unique qualities that Aston Martin owner Lawrence Stroll has bought into, hoping they will be the icing on the cake of an investment in facilities and staff that has already totalled hundreds of millions of pounds.

Newey, Stroll believes, is what is needed to turn his team into title contenders within a couple of years.

It is an expensive decision, but one founded on many years of evidence. Newey is as close to a guarantee of success as it gets in F1.

-

-

Published6 hours ago

-

-

-

Published4 days ago

-

On one level, his skill is to see in an arcane and complex set of technical regulations the secrets of what is possible to unlock the most performance. And performance in F1 is primarily to do with aerodynamics.

How can he do that better than probably anyone in history? It’s to do with the way his brain processes the nuances of airflow.

Newey is an aerodynamicist by trade, but he doesn’t just apply the physics and look at the numbers produced in wind tunnels and computer simulations. He can imagine the air and how it will move around the car, how the various flows will interact with each other.

In an interview in November, this writer asked him whether it was true what they said, that he could see the airflow. He laughed, and said: “Of course not.” But then went on to explain that was actually exactly what he did.

“I can picture it,” he said. “And that’s perhaps, if I try to be objective, one of my strengths, that I can actually picture things quite well in my mind’s eye.”

He claims this is not a unique quality, that he works with other talented engineers who can do the same. And doubtless that is true – Newey is an honest and principled man as well as the best in his field.

But it is also true that he has a unique ability to do this, one that seems to surpass anyone else’s.

Newey’s ‘uniquely rounded set of abilities’

Time and again, Newey’s car designs have set trends that others have had to follow, and quite often that has coincided with regulation changes – as it did for Red Bull in F1, from 2010-2013, and again now.

There is another big regulation change for 2026, and Newey arrives at Aston Martin in March next year in sufficient time to feed into that design.

Last year, Max Verstappen and Red Bull produced the most dominant season in F1 history, with 19 wins for Verstappen and 21 for the team out of 22 grands prix.

This year started with four Verstappen wins out of five. And while Red Bull no longer have the fastest car, and are fighting a rearguard battle against McLaren in both championships, their decline has coincided with Newey stepping back from involvement in F1 since early May, right after he negotiated an early exit from his contract.

It might be a coincidence, of course, that Red Bull have become lost in understanding what has gone wrong with their car since Newey stepped away from F1 – and the team are trying to play down any direct connection.

But it is hard to conceive that losing an engineer of such skill and insight has not had an effect.

Back in 2022, when this regulation set was first introduced, it became clear very quickly that Newey and his team at Red Bull – to whom he is always very quick to give credit – had hit upon the secrets of what was needed for the new rules.

These reintroduced venturi underfloors to F1 – a curved shape to the underbody like an inverted wing that produces aerodynamic downforce.

Essentially, the closer these cars run to the ground, the more downforce they produce. But there is a limit – they are prone to something called porpoising, where the car gets too low as it is sucked to the track and the airflow stalls, and the car starts a bouncing motion at high speed.

Having experienced venturi floors back in the early 1980s with an F1 team called Fittipaldi, and been witness to a few failed experiments, Newey realised that the secret was in the interaction of the aerodynamics and suspension.

Part of the holistic solution to this was his decision to invert the way suspensions worked in recent years, and especially how the suspension arm joins the wheel to the chassis.

The fashion had come to be push-rod at the front – the arm is attached to the top of the chassis and the bottom of the wheel hub – and pull-rod at the rear – the other way around. But for the best relationship of aerodynamics and kinematics, Newey flipped it for the 2022 Red Bull. Others have since followed suit.

Add that to an especially sophisticated underfloor design that left rival designers open-mounted in admiration when they first saw it, and you have the foundations for a period of dominance.

Newey says: “When we were looking at trying to understand not simply loopholes but also what was required to suit these regulations back in 2021, it was trying to get the fundamentals right, trying to get the architecture to suit the aerodynamic rules, suspension.

“So we decided to go pull-rod front, push-rod rear, which was opposite to what most cars had been in the previous rules. We felt that’s what best suited the aerodynamic requirements of the car. So I think we managed to get the fundamentals of the car right when it came out at the start of last year.”

Newey is able to see these key influencing factors because he has a uniquely rounded set of abilities.

A genius designer, and an aerodynamic visionary, he is also rooted in the practicalities of what a car needs to be fast. His extreme competitiveness, and lack of engineering arrogance, ensures a ruthless focus on performance.

So, for example, he understands that it is pointless chasing peak downforce figures if they are produced only in certain conditions and therefore create a car that is nervous and unpredictable to drive.

For Newey, it is all about accessing the maximum amount of performance for the maximum amount of time. It sounds simple, but it is a formula so many F1 designers seem to forget remarkably often.

There were smiles after Red Bull’s victory in the Saudi Arabian Grand Prix in March but tension has been building between team principal Christian Horner and Newey

How much will his move hurt Red Bull and help Aston Martin?

It is an imponderable question, but the beginnings of the answer to the first part look like they are already being seen.

The first-order reason for Newey’s departure from Red Bull is because he has been singularly unimpressed by the controversy surrounding team principal Christian Horner, who has been accused by a female employee of sexual harassment and coercive, controlling behaviour, which he denies. Two separate internal Red Bull investigations have dismissed the complaint.

But also in the mix have been tensions at the team as to where credit was due for the success of the cars. Horner has tended from time to time in recent years to downplay Newey’s influence, and talk up that of technical director Pierre Wache and aerodynamics chief Enrico Balbo.

Newey pushed back against this inside the team. Last year, after an interview Horner gave in which he addressed this topic, Newey is said to have sent Horner a detailed email explaining all the times he had made crucial interventions. His wife Amanda was less discreet about it – she went on social media to describe the claims as “a load of hogwash”.

The roots of the claims about diminishing influence were that at Red Bull, Newey was no longer full-time on F1. He invested about 50% of his working week on it. Wache leads what is clearly a remarkable team of designers, and the various departments report into him.

But that does not necessarily mean Newey was not hugely influential. Would Red Bull have hit on their design philosophy without his sprinkle of stardust, his vision for what was necessary?

There is only one reality; guessing the outcome of a different set of circumstances would be just that – a guess.

But the lesson of history would suggest Newey’s presence was critical – for the past 30 years in F1, there has been no better guarantee of a competitive car than that Newey was involved in its design.

At 65, he could have retired, live off his millions and gone sailing on his new luxury yacht. But he was never going to. You do not negotiate an early exit from your contract, ensuring you can work for a new team in time to affect their 2026 design, if you intend to kick back with your feet up and chill out.

Newey had talks with Ferrari, but their interest diminished.

At Aston Martin, they seem to have everything needed to become a success.

A brand new facility, plenty of resource, an expensively assembled engineering support structure, a works engine partnership with Honda, who are joining from Red Bull for 2026, and one of the greatest drivers in history in Fernando Alonso, who at 43 is still delivering, and with whom Newey has always wanted to work.

Last year, I asked Newey how long he meant to go on. He said that back when he was 50, he did not expect still to be working by now. But then he had discussed it with ex-F1 boss Bernie Ecclestone and US racing mogul Roger Penske, who are both, as he put it, “still working at quite a ripe old age and are still very mentality agile”. They both told him not to stop working.

“Unfortunately,” Newey said, “my father retired at 65, and kind of ended up a little bit lost, I suppose, if I’m honest. I don’t think he’d mind me saying that.

“So I am conscious of all these things. Equally, F1 is a very involving sport and I still love it.

“I have been fortunate enough to be doing what I wanted to do from about the age of 10 – be an engineer in motor racing. So while I still enjoy it, I would like to still be involved.”

Now Newey has made his decision. He will be around for another five years at least. And who would bet against him working his magic again?

A version of this article was first published on 2 May 2024