Why West has limited Ukraine’s use of its missiles

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThere are strong indications that the US and UK are poised to lift their restrictions within days on Ukraine using long-range missiles against targets inside Russia. Ukraine has been pleading for this for weeks. So why the reluctance by the West and what difference could these missiles make to the war?

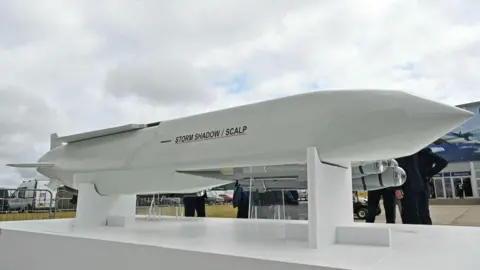

What is Storm Shadow?

Storm Shadow is an Anglo-French cruise missile with a maximum range of around 250km (155 miles). The French call it Scalp.

It is launched from aircraft then flies at close to the speed of sound, hugging the terrain, before dropping down and detonating its high explosive warhead.

Storm Shadow is considered an ideal weapon for penetrating hardened bunkers and ammunition stores, such as those used by Russia in its war against Ukraine.

But each missile costs nearly US$1 million (£767,000), so they tend to be launched as part of a carefully planned flurry of much cheaper drones, sent ahead to confuse and exhaust the enemy’s air defences, just as Russia does to Ukraine.

Britain and France have already sent these missiles to Ukraine – but with the caveat that Kyiv can only fire them at targets inside its own borders.

They have been used with great effect, hitting Russia’s Black Sea naval headquarters at Sevastopol and making the whole of Crimea unsafe for the Russian navy.

Justin Crump, a military analyst, former British Army officer and CEO of the Sibylline consultancy, says Storm Shadow has been a highly effective weapon for Ukraine, striking precisely against well protected targets in occupied territory.

“It’s no surprise that Kyiv has lobbied for its use inside Russia, particularly to target airfields being used to mount the glide bomb attacks that have recently hindered Ukrainian front-line efforts,” he says.

Why does Ukraine want it now?

Ukraine’s cities and front lines are under daily bombardment from Russia.

Many of the missiles and glide bombs that wreak devastation on military positions, blocks of flats and hospitals are launched by Russian aircraft far within Russia itself.

Kyiv complains that not being allowed to hit the bases these attacks are launched from is akin to making it fight this war with one arm tied behind its back.

At the Globsec security forum I attended in Prague this month, it was even suggested that Russian military airbases were better protected than Ukrainian civilians getting hit because of the restrictions.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesUkraine does have its own, innovative and effective long-range drone programme.

At times, these drone strikes have caught the Russians off guard and reached hundreds of kilometres inside Russia.

But they can only carry a small payload and most get detected and intercepted.

Kyiv argues that in order to push back the Russian air strikes, it needs long-range missiles, including Storm Shadow and comparable systems including American Atacms, which has an even greater range of 300km.

Why has the West hesitated?

In a word: escalation.

Washington worries that although so far all of President Vladimir Putin’s threatened red lines have turned out to be empty bluffs, allowing Ukraine to hit targets deep inside Russia with Western-supplied missiles could just push him over the edge into retaliating.

The fear in the White House is that hardliners in the Kremlin could insist this retaliation takes the form of attacking transit points for missiles on their way to Ukraine, such as an airbase in Poland.

EPA

EPAIf that were to happen, Nato’s Article 5 could be invoked, meaning the alliance would be at war with Russia.

Ever since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, the White House’s aim has been to give Kyiv as much support as possible without getting dragged into direct conflict with Moscow, something that would risk being a precursor to the unthinkable: a catastrophic nuclear exchange.

What difference could Storm Shadow make?

Some, but it may be a case of too little too late. Kyiv has been asking to use long-range Western missiles inside Russia for so long now that Moscow has already taken precautions for the eventuality of the restrictions being lifted.

It has moved bombers, missiles and some of the infrastructure that maintains them further back, away from the border with Ukraine and beyond the range of Storm Shadow.

Yet Justin Crump of Sibylline says while Russian air defence has evolved to counter the threat of Storm Shadow within Ukraine, this task will be much harder given the scope of Moscow’s territory that could now be exposed to attack.

“This will make military logistics, command and control, and air support harder to deliver, and even if Russian aircraft pull back further from Ukraine’s frontiers to avoid the missile threat they will still suffer an increase in the time and costs per sortie to the front line.”

Matthew Savill, director of military science at Rusi think tank, believes lifting restrictions would offer two main benefits to Ukraine.

Firstly, it might “unlock” another system, the Atacms.

Secondly, it would pose a dilemma for Russia as to where to position those precious air defences, something he says could make it easier for Ukraine’s drones to get through.

Ultimately though, says Savill, Storm Shadow is unlikely to turn the tide.