How friends became foes in Africa’s diamond state

AFP

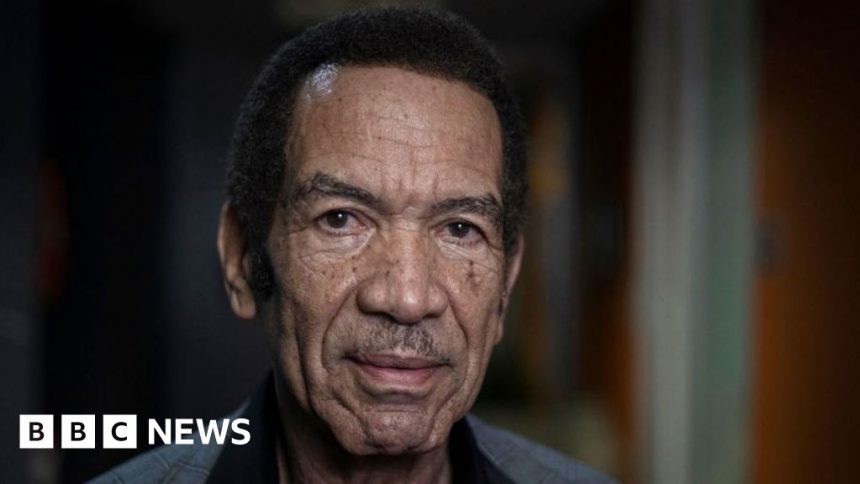

AFPIan Khama’s well-mannered voice barely disguises the anger that he feels.

In several interviews that Botswana’s former president has given since 2019, when he began to express dissatisfaction with his hand-picked successor, Mokgweetsi Masisi, he has talked about him in damning terms.

Masisi was “drunk on power”, Khama told the BBC’s Focus on Africa programme five years ago.

Since then the 71-year-old has gone into exile, spoken about a plot to poison him and been charged in Botswana with several crimes including money laundering and owning illegal firearms.

Having previously dismissed the charges as being “fabricated”, last month he returned home and appeared in court for an initial hearing.

The tension between Khama and Masisi is likely to colour the diamond-rich country’s imminent general election – just three weeks away – as the former president is actively campaigning for an opposition party.

At a further, brief, court appearance on Tuesday, Khama was all smiles.

The authorities are now believed to be considering if the case should proceed.

There is a strong possibility that things will come to a halt as Khama’s co-accused are no longer facing the charges. But the court will not reconvene until a month after the election.

AFP

AFPTo the outsider, who might have the general feeling that Botswana is one of the continent’s most stable democracies with strong institutions, this dispute between the current and former presidents may seem surprising.

The Botswana Democratic Party (BDP) has governed since independence from the UK in 1966.

In a constituency-based system, it has dominated parliament for the last five decades though its share of the vote in recent elections has hovered around 50%.

The country’s first president, and Khama’s father, Sir Seretse Khama, was descended from royalty and helped cement Botswana’s reputation for orderly government in the 14 years he was in power up to his death in 1980.

His 1948 marriage to a white British woman, Ruth Williams, was controversial and led to his exile in the UK.

Ian Khama, the couple’s second child, likened his own recent time in South Africa to that of his father’s period away from Botswana.

After having been in the military, he went on to become president in 2008, serving for 10 years.

Despite the dynastic appeal, the shine came off Khama’s government and in the 2014 election the BDP won less than 50% of the vote for the first time.

Concerns about corruption, human rights and the state of the economy – with high levels of unemployment – all dented Khama’s popularity.

In the Ibrahim Index of African Governance, funded by Sudanese telecoms mogul Mo Ibrahim, Botswana’s score dropped during his period in power.

The country’s huge diamond reserves have proved lucrative and seen the economy grow, but not enough jobs were being created for the young population and the wealth was not being spread around.

Innocent Selatlhwa

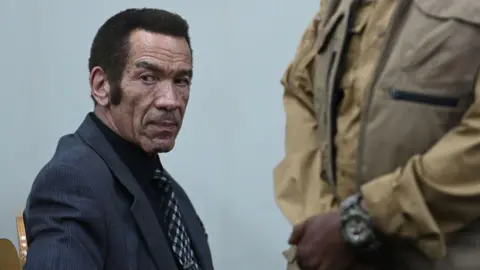

Innocent SelatlhwaIn 2018, Khama handed over the reins of power to his loyal vice-president, Masisi, perhaps hoping that he could still have some influence, but things soon went awry.

One theory is that there was a gentleman’s agreement that Masisi would appoint Khama’s brother, Tshekedi, as vice-president, which he refused to do.

Khama began complaining that his security detail was being cut and that democracy within the BDP was being undermined.

Masisi also reversed some key policies such as a ban on trophy hunting and ended the scepticism towards having closer relations with China.

A year after stepping down as president, Khama then joined the newly formed opposition Botswana Patriotic Front (BPF) telling the BBC at the time that the “democracy that we’ve been proud of in this country is now in decline”.

He then went into self-imposed exile in late 2021 alleging that there were threats to his life.

Masisi has batted away the criticism and earlier this year described the poisoning allegation as “shocking”.

“If you look at the history of either killings or murders in Botswana and the methods used, poisoning is not one of the ones we know best, but of late he [Khama] seems to be an expert,” Masisi told France 24, adding that the former president had nothing to fear.

Masisi also said that the arguments Khama has been using against the government and his leadership have been “a litany of inconsistencies”.

There is absolutely no chance of reconciliation between the former allies, and Khama is hoping to end the 58 years in power of the BDP – the party his father helped found.

There are opportunities to take votes from the government as the problems with the lack of jobs and the accusations of corruption have also dogged the current administration.

Furthermore, the former president still commands a lot of respect in the country, especially among the older voters and in his home area around Serowe, where he is paramount chief and where the BPF launched its manifesto at the weekend.

But Masisi and the BDP remain in a strong position, especially as the opposition is divided.

The 30 October poll offers an opportunity for the Khama dynasty to once again have an impact on the future of the country.

More BBC stories on Botswana:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBCGo to BBCAfrica.com for more news from the African continent.

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, on Facebook at BBC Africa or on Instagram at bbcafrica