‘It was a relief when my ex-footballer husband died after CTE’

Widows of ex-footballers diagnosed with CTE on the pain of seeing their husbands suffer

-

Published

-

Warning: This article contains references to suicide

“When he died, it was a relief. He was lying in bed, couldn’t talk, couldn’t eat, laid there with a nappy on. No-one would want to live like that, and I didn’t want him to live like that.”

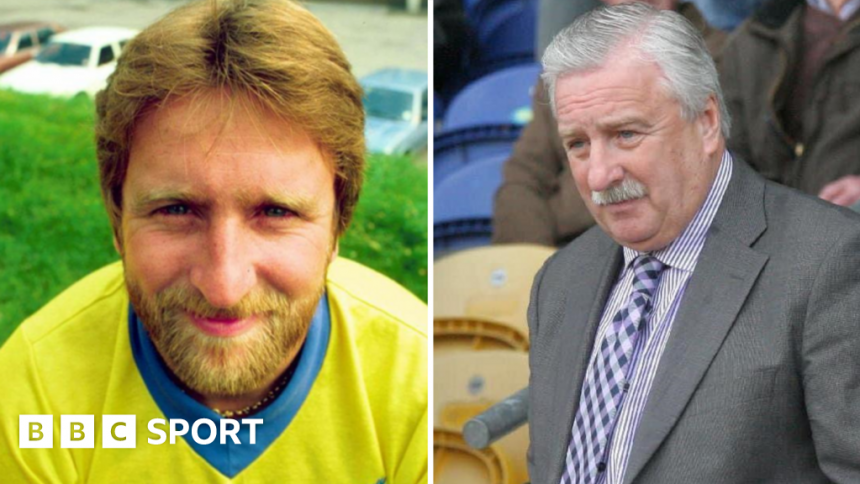

Sue Bird’s final years married to former Mansfield Town defender Kevin Bird were marred by grief and violence.

Her loving husband’s personality was decimated by dementia and he was finally sectioned in 2020. He never came home and died in February 2023.

Like the Bird family, Tina White began to worry about her husband Goff – a one-time semi-professional footballer who played for Ryde, Waterlooville and Basingstoke – when he developed an erratic temper that led him to behave with uncharacteristic aggression.

“His whole personality changed. Before, he had empathy. He was a very loving and passionate man towards me. But he became a totally different person, a person that I didn’t like. One day he got really aggressive and said he wanted to kill me.

“He wasn’t Goff – we lost Goff a long time ago.”

Sue and Tina believe repeatedly heading footballs killed their husbands.

CTE & football – the brief background

Kevin Bird heading the ball for Mansfield Town in 1977

The Bird and White families are part of a group whose footballer relatives were diagnosed with neurological conditions caused by chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).

CTE is believed to be caused by repeated blows to the head. However, a definitive diagnosis can only be given after death, as it requires analysis of the brain.

On Friday, a group of families – also including 1966 World Cup winner Nobby Stiles’ son John – will present medical submissions to the High Court in London in the latest stage of a legal challenge being brought against the Football Association, its Welsh counterpart and international football’s lawmakers Ifab. They are taking action over what they say are brain injuries caused by repeated impacts between head and ball.

Some of the families have also written to the Coroners’ Society to request all British sportspeople’s brains be tested for CTE after death to “force sports to adopt better protocols in respect of brain welfare” and “provide greater awareness of the risk of brain injuries for sports participants”.

BBC Sport spoke to the widows of ex-footballers about their experiences of dealing with CTE, which they say is also “an issue for the youth of today” not just “an old person’s disease”.

-

-

Published21 March

-

-

-

Published16 January

-

-

-

Published1 May

-

‘I think damage was done aged 18 to 20’

Tina White’s husband Goff was a senior project engineer and semi-professional footballer

In the decade leading up to his death earlier this year, Goff – a senior project engineer after his early football career – changed from the “larger-than-life character who loved telling jokes” into a shell of himself.

He was unable to work, undertake basic tasks, struggled with his speech and became prone to mood swings.

“We were married for 50 years,” says Tina. “The last 10 were hell.

“Goff was a prolific header of the ball as a footballer. I think the damage was done between 18 to 20 [years old], when he got a lot of concussions. He was a very aggressive player, in there with his head, and he would practise heading for hours.”

According to the NHS, CTE can cause depression and suicidal thoughts, personality changes, and increases in erratic and violent behaviour.

For Tina and her family, the outbursts of violence Goff suffered from were devastating.

“One day he just went berserk. I locked myself in the bathroom and rang the police, but he broke the lock on the door. I ran out and luckily the neighbours had come over, so I managed to open the door to them.

“He chased after me, punched me violently and he pulled me back. I think if they hadn’t been there he would have seriously hurt me that day.

“I said to the police: ‘Please don’t lock him in a jail cell. He’s sick, not a criminal.’ Then he got sectioned. He didn’t come home after that.

“I used to go to bed and cry every night, and I remember one night I thought it would just be easier if he died. That’s how bad you feel at times.”

After Goff died, Tina donated his brain for examination by Prof Willie Stewart – the pre-eminent neuropathologist who specialises in CTE cases in sportspeople and has advised sports bodies around concussion protocols.

Prof Stewart told Tina her husband’s brain was “totally tangled up with abnormal proteins and CTE deposits”.

“Former professional footballers are at much higher risk of degenerative brain diseases, dementias and related disorders,” says Prof Stewart, who is a consultant neuropathologist at the University of Glasgow. “What we see is the risk is about three and a half times higher than it should be.”

Prof Stewart says cases of CTE can be linked to repeated impacts such as heading footballs, because the pathology of the disease differs so much from other forms of dementia.

“We see this very unique change in the brain which only appears in athletes that we don’t see in other individuals,” he adds.

-

-

Published27 May

-

‘After New Year’s Eve attack, he never came home’

Mansfield legend Kevin Bird played over 450 times for the Stags as a no-nonsense defender through the 1970s and early 1980s. He died last year, aged 70.

“I left him in bed one day and came back in the afternoon,” says Sue, his wife of almost 40 years. “He was in the corner of the lounge with his hands on his head, crouching in the corner and just sobbing. He was repeating ‘I don’t know what’s the matter with me’.”

Kevin was initially diagnosed with Alzheimer’s with depression in 2013, but his condition deteriorated as he forgot how to do things such as cook and do the gardening.

“It was New Year’s Eve 2019,” Sue recalls. “He’d gone out the front door and was pacing up and down in front of the window. Eventually I helped him back inside. Then he attacked me – just went for me. He didn’t know who I was a lot of the time. I don’t know if he thought I was an intruder or what, but he attacked and injured me.

“They sectioned him. I thought they’d give him something to calm him down and he’d come home, but he never came home after that. He was completely gone by then.”

Post-mortem analysis of Kevin’s brain showed he was suffering from CTE.

‘Ex-players scared to death of ticking time bomb’

Bill Gates (top left) played for Middlesbrough from 1961-1974

Judith Gates, whose husband Bill retired from football the day before his 30th birthday due to persistent migraines after playing over 200 times for Middlesbrough, set up the Head Safe Football foundation following confirmation of his CTE diagnosis.

“In the last two or three years he could no longer talk, no longer walk, had difficulty swallowing – and so the physical symptoms kicked in alongside the cognitive ones,” Judith says. “You’re watching the person that you’ve loved melt away, and all that made them who they were gradually diminish.

“CTE is brutal. It brings mood issues. Bill went through a time of suicidal ideation, where he begged us to find him a gun. I had to hide every paracetamol in the house.”

Earlier this month The Telegraph reported, external that the FA tried to prevent an inquest into the role played by football in Bill’s death.

“This is an emotional situation,” Judith says. “To hear the FA wishing to disregard our family’s desire for the truth to be told about Bill was hurtful.”

A spokesperson for the FA told the BBC: “We reiterate our sympathy for the Gates family. Whilst we do not think it is appropriate to comment on an ongoing inquest, our position is that the question of any potential links between football and neurodegenerative disease is clearly a matter of public interest which needs to be handled appropriately and properly.”

Judith has found purpose in trying to ensure no other footballers suffer the same fate as Bill. Head Safe Football aims to safeguard players, professional or amateur, from CTE by educating them about ways heading can be reduced in training.

“I’m absolutely certain that it’s a ticking time bomb,” Judith says. “I spend a fair bit of time with players who are in between playing the game and having demonstrable symptoms. What I’m finding from conversations with them is they are scared to death.”

For Professor Stewart, focusing on reducing less crucial contact between head and ball is the key.

“A significant proportion of footballers may be affected by this, if they get to the age where dementia is a problem,” he says.

“We sat with some of the families and worked out that some players may head the ball 70,000 times over a 10-15 year career, but only a fraction of those – one or two thousand of them – may have occurred during matches. So, we can get rid of 90% to 95% of head impacts just by keeping heading for the match.”

There are rules across England, Scotland and Wales restricting heading in children’s games, while different restrictions are in place around training in the English and Scottish professional games.

All three widows want heading reduced, rather than banned, and more education of young players about the dangers of CTE.

A spokesperson for the FA told the BBC: “We continue to take a leading role in reviewing and improving the safety of our game. This includes investing in and supporting multiple projects in order to gain a greater understanding of this area through objective, robust and thorough research.

“We have already taken many proactive steps to review and address potential risk factors which may be associated with football whilst ongoing research continues in this area, including liaising with the international governing bodies.”

Related topics

-

-

Published6 June

-