‘Death trap’ Channel boats traded by smugglers in German city – BBC undercover

BBC

BBCIt costs €15,000 (£12,500) for the whole “package”, we are told. For that we would be given an inflatable dinghy, with an outboard motor and 60 life jackets, to get across the English Channel.

This is the “good price” offered by two small-boat smugglers to an undercover BBC journalist in Essen – a western German city where many migrants live or pass through.

A five-month-long BBC investigation has exposed the significant German connection to the lethal human smuggling trade across the English Channel.

As the new UK government promises to “smash the gangs”, Germany has become a central location for the storage of boats and engines eventually used in Channel crossings – confirmed to the BBC by Britain’s National Crime Agency.

During covert filming, smugglers revealed to us that they store boats in multiple secret warehouses – as they play cat-and-mouse games with German police.

This year is already the deadliest for migrant Channel crossings, UN figures show, while more than 28,000 people have so far made the journey in small, dangerously packed boats.

__

Our undercover reporter is waiting outside the central station in the city of Essen.

He is wearing a secret camera and posing as a Syrian migrant, eager to cross the Channel to the UK with his family and friends.

He must remain anonymous, for his safety, but we will refer to him as Hamza.

He approaches a man. It is someone Hamza has been in touch with for months, via WhatsApp calls, after getting his number through a contact within the migrant community – but this is the first time they have met.

This man’s name – or at least the name he has given us – is Abu Sahar.

Since Hamza contacted him, they have discussed how Sahar can help provide a dinghy to get to the south coast of England.

Hamza has told him that bad experiences with the smuggling gangs in the Calais region have driven him, his family and friends to try to manage their crossing alone – an unusual step.

Sahar has already sent a video of an inflated dinghy which, he has suggested, is “new”, available and being kept in a warehouse in the Essen area.

He will go on to supply more footage including other, similar looking, boats as well as outboard engines being fired up.

Hamza has said he wants to check the quality of the items on offer himself and that is why he has insisted on an in-person meeting.

A BBC team is nearby, monitoring Hamza’s movements, in case anything goes wrong, or we need to extract him quickly.

As the two men walk through the centre of Essen, Sahar declares it is too “risky” to go to the warehouse to see the boat, even though he says it is less than 15 minutes’ drive away.

When Hamza asks about why the boats are kept in this part of Germany, Sahar talks about “safety” and “logistics”.

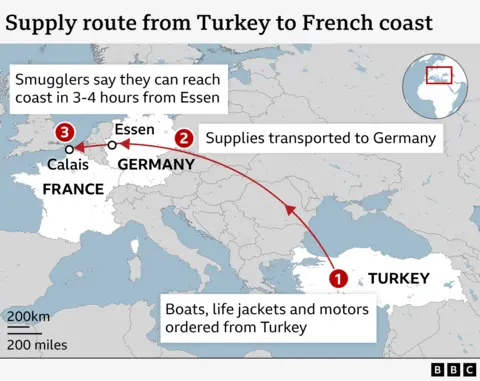

Essen is just a four- to five-hour drive from the Calais area – close enough to get boats there fast, but not too close to the more heavily monitored beaches of northern France.

While police raids do happen, the facilitation of people-smuggling is not technically illegal in Germany if it is to a third country outside of the EU, which the UK now is after Brexit.

The interior ministry in Berlin argues that, because Germany and the UK aren’t geographical neighbours, “no direct smuggling” actually takes place – but a UK Home Office source told the BBC there is “frustration” about Germany’s legal framework.

Sahar takes Hamza to a café where they order coffees and light cigarettes, although they move tables because there are Arabic speakers next to them and Sahar doesn’t want to be overheard.

Just over 35 minutes later, Sahar gets up out of his chair and tells Hamza: “Lower your voice, he’s coming.”

A well-dressed man in a baseball cap approaches. He is referred to as “al-Khal”, which means “the Uncle” – a phrase in Arabic that implies someone commands significant respect.

Khal is accompanied by another man who will remain largely silent, but appears to be his bodyguard.

There are some handshakes before Khal talks to the waitress in German and then switches back to Arabic, his native tongue.

Hamza is told to hand over his phone, which is placed on a separate table.

The bodyguard sits next to Hamza and will spend much of the next 22 minutes staring intently at him.

During the meeting, because of strict German law, the BBC can only record video, not the audio.

Our reporting of it is therefore partly based on the immediate recollection of our undercover journalist – an established method in German investigative reporting.

It is backed up by messages, call records and voice notes between Hamza and the smugglers.

“Don’t raise your voice,” says Khal as he instructs Hamza to explain who he is and what he wants.

Hamza repeats his cover story, apparently convincingly.

He also suggests the boat purchase they are now discussing may not, in fact, even be illegal because of grey areas in German law.

But Khal dismisses that suggestion.

“Who told you that?” he asks. “It’s not legal.”

Even if there are legal loopholes in Germany around boat-smuggling, it appears these men know they are involved in a wider criminal network.

During their coffee, Khal sometimes prods Hamza in the chest as the smugglers disclose they have about 10 warehouses in the Essen area.

That, it is implied, is a way of dividing up their goods in case of a police raid – which there was a “few days ago”.

Sometimes, it is suggested, they get word the police are coming and give them “bait” – meaning supplies are confiscated but seemingly not enough to seriously disrupt the operation.

Gareth Fuller/PA Wire

Gareth Fuller/PA WireThe smugglers talk about their ability to get equipment to Calais within “three, four hours”, which indicates they feel bold enough to use motorways, rather than back roads.

Essen’s location means boats can be delivered within a morning or afternoon, should a good weather forecast prompt a surge in crossing attempts and therefore demand.

According to research by the Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime, boats are typically transported by vans or cars from Germany, Belgium or the Netherlands to the French coast, with Germany a “particularly important transit point”.

Most of the vessels, they found, have been manufactured in China before being sent, by container, to Turkey and then moved into Europe.

One of the report’s authors, Tuesday Reitano, says Germany’s role as a hub has grown for various reasons including robust “anti-smuggling controls” in France, which have driven increasingly organised gangs to operate over longer distances.

She also believes the German authorities are less engaged with the issue of Channel crossings because, “It’s not a problem that’s on their border”.

Back at the cafe, Khal is apparently satisfied that Hamza is legitimate and starts talking money.

His preference is that Hamza takes the “package” deal which will cost €15,000 (£12,500).

That involves collecting the boat near Calais, along with an engine, fuel, pump and 60 lifejackets – more than Hamza has said he needs, but that is the blanket offer, and one that would more likely be made to a fellow smuggler directly organising the crossings in France.

Those smugglers’ profits are potentially “extraordinary” if you assume adults are being charged about €2,000 (£1,660) for a single trip with dozens of people on board – according to Global Initiative.

If a deal is agreed now, Khal claims he could get a boat to a location that is just 200m (655ft) from the French shoreline, by as soon as tomorrow.

Khal and Sahar also refer to a “new crossing point”, suggesting they have found a place less under the eye of the French authorities, though they don’t reveal its location.

There is a second, cheaper option, which Hamza has been pitching for all along.

For about €8,000 (£6,670) Hamza could pick up the boat himself, here at a warehouse in Essen, and drive it to northern France independently.

If you get caught, the smugglers tell him, we are not responsible.

Conversation turns to how Hamza would pay the gang, once he has decided what to do.

Khal wants the cash paid in Turkey, because “all the stuff” comes from there.

The money, he suggests, can be deposited through the Hawala system – a payment method that avoids formal banking and instead relies on a network of agents to deliver cash across borders.

Later, Hamza is sent an account name on WhatsApp.

Other messages and voice notes in Arabic, also sent after the café meeting, include Sahar describing brands of outboard motors. He “loves” Mercury ones, he says, although “if there is Yamaha, I prefer Yamaha”.

He talks about how they can “deliver and bury” the gear, implying it can be hidden underground near a crossing point, with Boulogne a better option because, “Calais, it’s hard”.

In what appears to be a sales pressure tactic, Hamza is also told the smugglers have “limited” stocks but plenty of buyers.

Khal is more careful in his communications, but in one voice note, forwarded by Sahar, he expresses unease after meeting Hamza, saying: “Your friend, he seems not OK.”

Nevertheless, he instructs Sahar to get a decision from Hamza about whether he wants to buy a boat or not: “Ask him in the next one or two hours.”

Eventually, Hamza tells them he can no longer go ahead with the deal.

The BBC paid no money to these men, whose real identities we have not been able to establish definitively.

We have shown footage we received of the boats to the Chair of the National Independent Lifeboat Association, Neil Dalton, who says he wouldn’t go in a “duck pond” in such vessels.

Comparing one to a “death trap”, he says it would be “appallingly dangerous” to pack dozens of people onto these boats for a Channel crossing, because of what appears to be a “tremendously flimsy” design.

Meanwhile, diplomats insist that co-operation between Germany and the UK, on tackling these gangs, has improved.

Arrests and warehouse raids have happened in Germany, in partnership with other countries – while so-called “collateral crime”, such as violence or money-laundering, can be prosecuted within Germany.

February saw a major raid where boats, engines, life vests and flotation devices for children were seized in Germany with 19 arrests – but these were made under Belgian and French judicial orders. A separate trial, following a similar operation in 2022, is being prosecuted in France.

A UK Home Office spokesperson told the BBC the government is “rapidly accelerating” work with countries, including Germany, to “crack down on the criminal smuggling gangs”, but “there is always more to do together”.

A joint action plan is being developed with Germany, while the UK’s new Border Security Command will be “essential” in dismantling criminal networks, they added.

That sentiment is echoed by the French authorities.

“It is important to demonstrate to the Germans that these boats are linked to offences on our coasts, which will allow them to intervene,” Pascal Marconville, a prosecutor in northern France, told the BBC earlier this month.

Berlin’s interior ministry told the BBC that bilateral cooperation was “very good” and that German authorities can take action at the request of the UK.

A spokesperson added that while it isn’t illegal to aid smuggling from Germany to the UK, it is punishable to aid smuggling to Belgium or France, where Channel crossings take place.

Along the shores of north-eastern France, you can find the remnants of failed crossing attempts on boats that, according to the National Crime Agency, are becoming “ever more dangerous and unseaworthy”.

The deflated dinghies and abandoned life jackets on these beaches may look worthless, but someone will have paid huge sums for what they hoped was a route to a better life.

It is a trade in misery, desperation and, in the worst cases, death – but one that continues to evolve and thrive deep inside Europe.