Springsteen: I rarely see my bandmates – we’ve seen each other enough

“The louder you can talk, the better, because I’ve played rock and roll for 50 years.”

Bruce Springsteen has just E Street Shuffled into the room. Uncannily charismatic, he carries the practised ease of someone who knows the destabilising effect their presence can have on regular people.

He takes time to greet every member of the BBC’s film crew individually, then breaks the ice with a joke about a journalist who mistakenly called him “Springstein”. That reminds me of a local radio DJ in Belfast who always used to introduce him as “Bruce Springsprong”.

“Really?” he laughs. “Well, I’ve been called worse.”

In fact, we’ve been pre-warned that he doesn’t like being called The Boss – the nickname coined in the early days of his career with The E Street Band, when he’d be responsible for collecting and distributing the takings after a show.

“I hate being called ‘Boss’,” he told Creem magazine in 1980. “Always did, from the beginning. I hate bosses. I hate being called the boss.”

The term is conspicuously absent from his new Disney+ documentary, Road Diary, which charts the process of putting together Springsteen’s first tour since the pandemic – from handwritten notebooks to footage of his band “shaking off the cobwebs” after six years apart.

At times, the preparations lack the rigour you might expect.

“It’s all a little bit casual,” frets Steve Van Zandt, Springsteen’s guitarist and one of his oldest friends, after the star calls time on rehearsals.

“There’s a certain percentage [of songs] that we’re gonna [screw] up anyway,” Springsteen retorts.

“That’s what they’re paying for. They want to see it live. That means a few mistakes!”

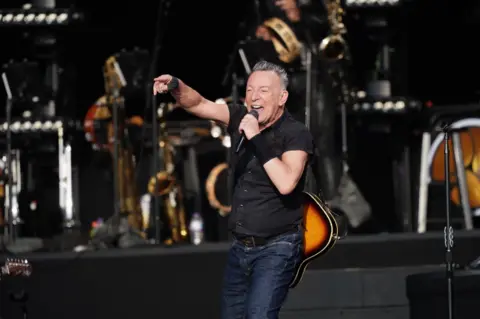

PA Media

PA MediaIf you’ve caught any of the star’s recent shows, you’ll know the stakes are never that high. The band are tighter than a tourniquet. Mistakes are noticeably absent.

The documentary comes exactly 60 years after Springsteen’s first gig, playing an $18 guitar with a band called The Rogues.

He’s never let anyone film the inner workings of his shows before, so why do it on this tour?

“Well, because I could be dead by the next one,” he laughs.

“I’m 75 years old now. I’ve decided that the waiting-to-do-things part of my life is over.”

“We’re closer to the end than we are to the beginning,” agrees Van Zandt, “but the point of this tour was that we’re not going out quietly, man.

“We’re going to balance that mortality with vitality.”

That philosophy was fully on display at Sunderland’s Stadium of Light in May, when Springsteen braved torrential rain to play for three hours to 50,000 drenched fans.

The weather was so brutal that Springsteen lost his voice. Doctors ordered him not to sing for a week, forcing him to postpone several shows.

What made him continue?

“Well, I’m there to have a good time,” he says. “I’m going to insist on it, whether it’s raining or the sun is shining – because I’m there for the people that are there.

“I look out and I go, ‘These are my people. These are the people who’ve listened to my music for the past 30 or 40 years. I’m going to do the best show I possibly can’, you know?

“It sounds corny, but you have to love your audience and, for the most part, I’ve never found that hard to do.”

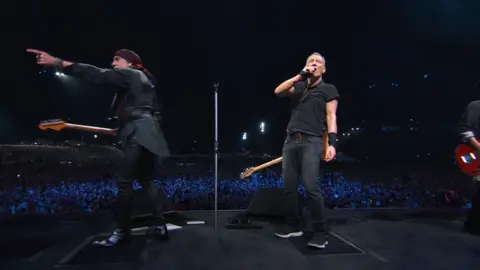

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt took audiences a while to reciprocate, however.

Born in New Jersey, to Douglas Springsteen, a bus driver, and Adele Springsteen, a secretary, Bruce paid little attention to music until he saw Elvis Presley on the Ed Sullivan Show and bought himself a guitar.

He spent his teens playing around the city with a Beatles-inspired band named The Castiles (after a brand of shampoo), taking gigs wherever they’d have him.

“I’ve played pizza parlours, I’ve played bowling alleys. I’ve played [psychiatric] hospitals and Sing Sing prison. I even played a supermarket opening once,” he recalls.

An introvert dancing on the tables

Back then, the setlist was all R&B covers and Motown hits – but Springsteen was a nervous performer.

In his autobiography, he talks about blinking 100 times a minute and chewing his knuckles. Van Zandt calls him “the most introverted guy you’ve met in your whole life”.

So how did he become the performer who, with the E Street Band, started tearing up stages all around the world?

“Introversion is a funny thing,” he says. “There’s a yin and a yang to it.

“On my own, I can be very internal. I’ve written a lot of internal music – Darkness On The Edge Of Town, Nebraska, parts of The River – all about people who live these very intense, borderline violent, internal lives.

“But the joyful side of me, which I got from my mother, allows me to sing Rosalita and Born to Run and Hungry Heart.

“I’m Irish-Italian, so I got the blues and I got the joy at the same time.”

It’s a typical Springsteen answer – analytical, sincere, intrinsically linking his life to his music.

Van Zandt, who witnessed Springsteen’s transformation, sees it differently.

“His first two records didn’t do well. Record companies were ready to drop him. His only dream was about to die.

“So my very shy friend reaches inside and says, ‘I’ll put the guitar down and start fronting the band’, which is huge move, right? Because the guitar’s a defence, it’s actually a wall between you and your audience. So he had to put that away and learn a whole new craft.”

It all came to a head at New York’s Bottom Line Club, shortly before the release of Springsteen’s breakout album Born To Run in 1975.

Over the course of five nights and 10 shows, the star showcased his new sound to fans, journalists and radio progammers.

“And all of a sudden, he’s dancing on the tables,” Van Zandt recalls. “I’m like, ‘Wow, where’d that come from?’

“I think it was sort of a defensive urge, like, ‘You’re not going to stop me’.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhatever it was, it worked.

Born To Run was a massive commercial success, selling six million copies in the US alone.

The album was constructed with the same desperation as those live shows, pieced together over 14 months (six of them on the title track alone) as Springsteen fought and scraped to save his career.

The songs – Thunder Road, Jungleland, Born To Run – throbbed with longing, as his characters fought to escape the confines of small-town, blue collar American life.

It’s a story he was familiar with. As a child, he witnessed the chilling effects of unemployment and the Vietnam War on his neighbourhood.

His subsequent rise to fame reads like a movie treatment for the American Dream, but he’s aware that luck and timing played a role.

No drama policy

“I wouldn’t want to be a young band starting today,” he says. “The day of the quote ‘rock star’ is in twilight.

“But I’ve had some encouragement. My young friend, Zach Bryan, just sold out two stadium nights in Philadelphia, so there’s still some young people coming up.”

No-one can match Springsteen, though, and he’s increasingly aware that time’s against him.

His last two albums confront mortality head-on, prompted by the realisation that he was the “last man standing” from his teenage band The Castiles.

On tour, he pays tribute to the E Street musicians who’ve crossed The River. Meanwhile his wife, Patti Scialfa, has cut back her appearances with the band, after being diagnosed with myeloma, a rare blood cancer, in 2018.

“She’s doing well, we caught it early,” Springsteen says.

“She’s having a tough time at the moment because she needs to have a shoulder replaced and a hip replaced. So that, on top of the myeloma, makes it very difficult for her to get out and get around.

“But she’s made a beautiful new record that’ll be coming out, hopefully, this year. And we’ve been married for 34 years. I love her to death.”

Disney

DisneyDespite the realities of age, Springsteen isn’t slowing down. He’s back in Europe next summer to make up for the concerts he missed after Sunderland, adding another 12 dates for good measure.

“Do you think you can outlast The E Street Band?”, he demands every night, daring the audience to meet their energy, joule for joule.

Their shared history is the show’s heartbeat. Famously, they’ll take requests from the audience, often playing other artists’ songs at the drop of a hat. Springsteen traces that ability back to their early club gigs.

“I know every song these guys have ever played, so I’ll go, ‘Oh yeah, we played that back in 1964, I think we can fake our way through that one’.”

And the secret to their 50-year camaraderie? Distance.

“When we’re not playing, we rarely see each other,” Springsteen confesses. “We’ve seen each other enough!”

He continues: “The arc of most bands is to break apart.

“Even two guys can’t stay together. Simon can’t stand Garfunkel, Don couldn’t stand Phil Everly, and then you have the kids in Oasis… so the tradition carries on.

“It’s the nature of people to not get along, so that’s something you need to write into your projection of the kind of band you want to be in.

“I don’t like drama. I don’t want people knocking heads. I don’t want to hear about a bunch of bull backstage. I don’t put up with any of that stuff. We weeded it out a long time ago.

“The band started out crazy and made its way to sanity.”

In the documentary, Springsteen promises they’ll keep playing “until the wheels come off”.

I wonder if that’s because, as he’s said in the past, the shows help him fend off depression.

“I’ve been pretty lucky with the depression,” he says “It hasn’t bothered me in quite a while, but I definitely go on stage to lose myself.

“You have to surrender to the moment and see what comes up. Learn a little bit about yourself.”

What has he learnt on his latest tour?

“Let me see,” he says, leaning back to think.

“I learnt that my back really hurts a lot.”

Road Diary: Bruce Springsteen and The E Street Band premieres on 25 October on Disney+.