Immigration cuts: Why prime ministers keep failing to meet their targets

BBC

BBC“No more gimmicks. No more gesture politics. No more irresponsible, undeliverable promises.” These were the words of Sir Keir Starmer at last week’s Interpol conference on the subject of immigration.

He was building on the position he had laid out at the Labour party conference, in which he said: “It is the policy of this government to reduce both net migration and our economic dependency upon it.”

Sir Keir is not the first prime minister to make what appears to be a straightforward promise on immigration. The problem he faces is that pretty much all of his predecessors broke theirs. What makes him think he will be any different?

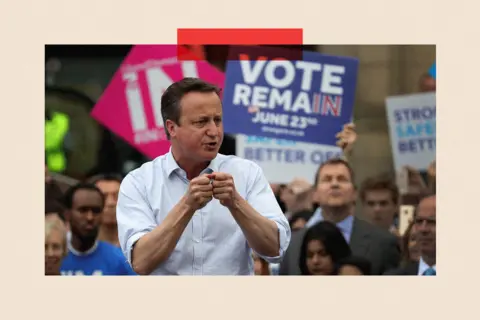

Promises on immigration have been the stock in trade for the last 15 years of UK politics. A pledge to get net migration – the number of people entering the UK for more than 12 months, minus the number leaving – down to the ‘tens of thousands’ was first offered by Cameron in the 2010 Conservative manifesto and remained there for the next two elections.

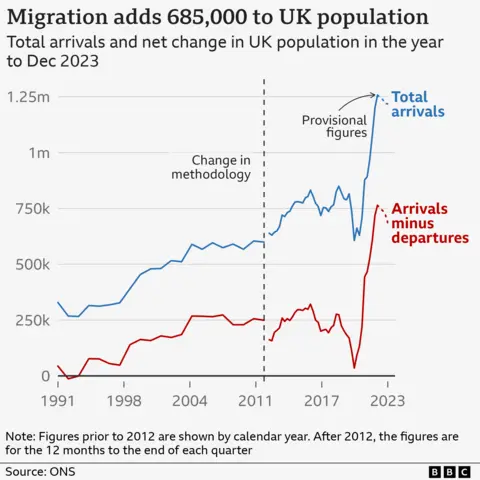

Yet, far from being fulfilled, migration almost consistently remained above 200,000 and reached more than 300,000 in 2016 – right in the middle of the Brexit referendum campaign.

Getty Images

Getty Images“Once those numbers came out [Cameron] was finished” says Alan Johnson, Labour’s Remain campaign chief.

Brexit victor Boris Johnson was widely expected to make good on his referendum statement that voting Leave in the Brexit referendum was “the only way to take back control of immigration”.

He dropped the tens of thousands target as part of his plans for an “Australian points based system” but in the run-up to the 2019 election as he sought a parliamentary majority to vote through his Brexit deal he insisted “numbers will come down because we’ll be able to control the system.”

Instead, by the time his premiership ended in the early autumn of 2022, it had reached 607,000. That figure would eventually rise above 700,000.

Immigration: How British Politics Failed

A new documentary uncovers how the debate around this issue brought politics to crisis

Rishi Sunak, once prime minister, in the face of these ballooning figures continued to promise to bring down legal migration, even promising to introduce a cap if he won the 2024 general election.

So many promises, so many failures. But why?

Cameron has his own take on that. Speaking in a new BBC documentary about the issue, he puts it down, in part, to the economic and employment crisis that began in 2012 and saw young people from Europe head to the UK for work. “The eurozone crisis was a real setback and that wasn’t something I had predicted,” Cameron says.

Others we spoke to – among them Home Secretaries and Immigration Ministers including Suella Braverman, Robert Jenrick and Damian Green, as well as senior civil servants and key government insiders – had their own explanations.

Some forces, they say, were unforeseeable – such as the issuance of hundreds of thousands of visas to those fleeing Hong Kong in the early 2020s, and Ukraine in 2022. But a far more common suggestion is that it results from inbuilt political dysfunction.

A “fundamental dishonesty” from government

Former ministers described to us the competing goals of major government departments, for example a Home Office attempting to keep numbers down, in opposition to a Treasury that wants tax revenue from more workers, a Health ministry that’s reliant on overseas workers to keep the NHS functioning and a Business department that wants to attract entrepreneurs.

“There has been a fundamental dishonesty about immigration policy,” says Anand Menon, Professor of European Politics at King’s College London.

“Many of the economic departments in government want more immigrants whilst the Home Office’s line tends to be, we want to stop immigration. Governments have been perfectly content to let those two narratives just sit side by side without explaining any of the trade-offs to the public.”

The most hardline migration-sceptics argue that the deception goes even deeper – they claim that it is the result of a fundamental presumption baked into the political system in favour of large-scale migration.

Speaking about this subject, Braverman, who was home secretary under Rishi Sunak between 2022 and 2023, told us: “The broader objection that I would get from the prime minister and from the chancellor of the exchequer and other ministers, was that if we were going to cut immigration, then we would be actually cutting revenue”.

She told us of “one conversation I had along the lines of, ‘Well, Suella, if you want to halve net migration to 300,000, you realise that’s going to cost us £3 billion. That’s the same as a cut to income tax.’”

Former Immigration Minister Jenrick described a discussion he once had with Prime Minister Sunak: “He put forward the argument that mass migration was a good thing because undercutting British workers’ wages was helping to bring down inflation. I was shocked.”

Sunak did not wish to comment on Jenrick’s recollection of their conversation but former Home Secretary James Cleverly argues against any suggestion that Sunak didn’t want to deliver on cutting legal migration: “The figures that came out in August of this year showed that year on year, every single metric that I was responsible for – illegal migration, net migration, asylum application numbers, growth rates, deportation rates – every single one of those accountability lines was trending in the right direction.”

But given the difficulties predicting the ebbs and flows of migration, how did numbers become so fundamental to the whole immigration debate?

It was politicians who made that call, in part responding to public pressure. But it was also made possible, in part, by the emergence of a research and campaign group named Migration Watch.

The question of how to calculate targets

The group was founded in 2001 by a former UK ambassador, Lord Green, and an Oxford demography professor, David Coleman. They were worried too many people were arriving in the UK.

Green told us: “We wanted to see strict limits on immigration confined to people we really needed, and at a scale that was not going to disturb the nature of our very historic and peaceful country.”

Green was keen to avoid charges of bigotry or racism. “We were still living with the memory of Enoch Powell and the things that he had said,” he explained. “Some of the things he said were right.

“Of course, immigration was much too high and would have implications etcetera. But he overshot very seriously… so we had to be particularly careful not to appear to be part of any such movement.”

Migration Watch’s solution was to move the UK’s ‘immigration debate’ away from race, onto the territory it occupies today – that of numbers. Some say Green’s insight changed everything.

“Migration Watch were very, very important,” says David Yelland, a former editor of The Sun, “because they put numbers on the problem and once you have numbers, you have an irresistible force in the newsroom.”

In 2003, on the BBC’s Newsnight, Jeremy Paxman used Migration Watch talking points to repeatedly press the Home Secretary, David Blunkett, asking him to state a maximum size for the UK population. Blunkett famously replied that he saw ‘no obvious upper limit’.

The resulting controversy was ‘gold dust’ for Migration Watch, says Green. Numbers were now at the heart of the immigration debate.

Tory leader Michael Howard also found value in Migration Watch’s arguments. He agreed with their belief that the number of people entering Britain should be capped, promising an annual limit at the 2005 election. When David Cameron became Leader of the Opposition later that year, he initially resisted the temptation to impose a cap, but he too became convinced that a number was deliverable.

Once the pledge was made, the presence of numbers in the immigration debate was fixed for good or ill. It certainly didn’t help Cameron. The pledge would become, in the words of former No.10 Communications chief Craig Oliver, “a stick to beat him with” during the referendum campaign which ended his premiership.

From Switzerland to the US: global caps

So, focusing on numbers – great in theory, problematic in practice. Yet others are flirting with it: Switzerland currently faces a referendum – not expected to take place before 2026 – on whether its population should be capped at 10 million, after a successful campaign by the right-wing Swiss People’s Party.

And in the United States, Vice President-elect JD Vance has put a figure on the number of people in the country illegally that the incoming second Trump administration will seek to deport. It should “start with 1 million”, he has said.

But in the UK, some question whether the figures are calculated in an effective way. For example, one former universities minister described their frustration that overseas students are included in immigration statistics, given the temporary nature of their time in the country.

Others believe net migration makes little sense as an abstract figure. Statements of the UK population growing annually by a total equal to the population of a city such Oxford or Nottingham – as popularised by Migration Watch and employed by politicians including Boris Johnson and Nigel Farage – don’t give a true impression of the dispersal of those arrivals, nor of how successfully or poorly they are absorbed into existing demand for public services.

Former Labour Home Secretary Charles Clarke is one of those who believes that the discussion about numbers is “entirely shallow”.

“There’s a ‘Britain is full’ approach to things,” he says, “and I thought it in a pernicious way actually sought to poison public debate.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAs for Sir Keir, he has been careful to put no figure to his newly-issued promises to reduce both net migration and irregular migration. But it seems likely that even without any action from his government, net migration will fall due to the Sunak government’s tightening of the Johnson-era visa regime, and the slowing of those from Hong Kong and Ukraine seeking entry.

The prime minister also appears to be striving to frame illegal boat crossings as a law-and-order issue rather than an immigration issue.

Yet, like leaders before him, Sir Keir will no doubt face further pressures during his leadership – whether further global conflicts, climate crises, or economic shocks – that displace people toward Britain.

The question that remains is, when that happens, will he be able to keep numbers from rising again – and tackle the challenges that have defeated so many prime ministers before him?

Top picture credit: Getty Images

BBC InDepth is the new home on the website and app for the best analysis and expertise from our top journalists. Under a distinctive new brand, we’ll bring you fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions, and deep reporting on the biggest issues to help you make sense of a complex world. And we’ll be showcasing thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. We’re starting small but thinking big, and we want to know what you think – you can send us your feedback by clicking on the button below.