‘Starmer – meet us before it’s too late,’ nuclear test veterans say

BBC

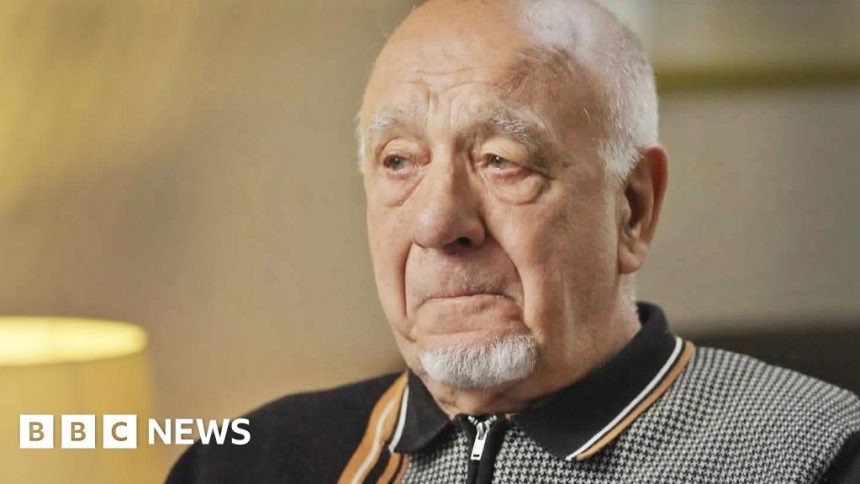

BBCWhen 18-year-old John Morris stood for the first time on the Pacific’s Christmas Island in 1956, he had no idea that the destructive forces of nature he would witness, harnessed for military power, would hang like a mushroom cloud over his life forever.

Now 86, Mr Morris is one of the last few of 22,000 personnel who witnessed the UK’s nuclear bomb tests – and those that are able to are still fighting to find out what it did their bodies.

A BBC film, to be broadcast this Wednesday, details their battles for what the dwindling band of men believe is a hidden truth: that the UK’s military knew at the time it was subjecting them to radiation that would damage them and their descendants forever.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThousands of the men have suffered cancers and other conditions that other nuclear states have recognised as probably linked to the now-banned testing.

But not the UK. It has paid no compensation at all.

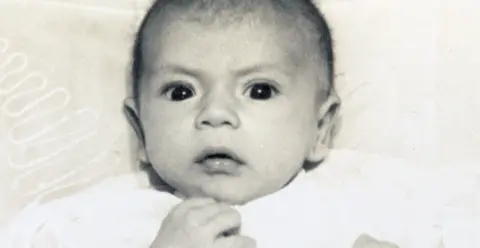

In Mr Morris’s case, as the film reveals, he believes the death of his first child, Steven, in 1962, was the result of the radiation damage he suffered during Operation Grapple – the name given to a series of British nuclear weapons tests.

Steven was four months old when he died in his cot. The coroner suspected the baby’s lung had not properly formed. Why? Nobody knows.

John Morris

John Morris“The death certificate said he died of pneumonia,” says Mr Morris.

“If that little baby got pneumonia when we put him to bed that night we would have known.

“The only time I really, really understood was when the undertaker came with his coffin. A little white box. It was the hardest day of my life.

“I blame the Ministry of Defence and the experiments they did on us for Steven’s death – and I always will.”

John Morris’s story is one of many testimonies in the film, which also covers what happened to Indigenous communities who lived in the nuclear bomb test areas in Australia.

All of them believe they were lab rats, subjected to live human experimentation as the British raced to join the USA and Russia as a nuclear power.

And they are appealing to Sir Keir Starmer to meet them – to make good on what they believe was a pledge made by the Labour party.

Labrats international

Labrats internationalThe campaign for disclosure and damages for ill health began decades ago as the veterans linked health conditions, cancers and birth defects in children to the nuclear testing that began in 1952.

But in 2012, the Supreme Court ended the campaign for damages, saying the men could not prove the link – and they had also long run out of time.

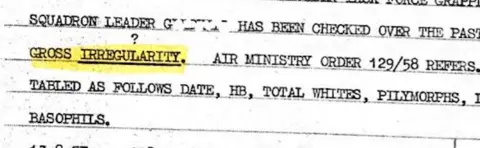

The campaign, however, was relaunched last year thanks to potentially crucial new evidence discovered in what is known as the “Gledhill memo”.

The 1958 report from Christmas Island to the nuclear programme’s secret UK headquarters says that there were blood tests for Squadron Leader Terry Gledhill showing “gross irregularity”.

The memo, says the campaign, is proof that blood tests were being taken from personnel – and that there was a continuing but secret plan to monitor them.

The circumstantial evidence has grown since. This year, 4,000 pages of documents from the Atomic Weapons Establishment were declassified after a long Freedom of Information fight.

Those documents are still being analysed but the campaign says they show there were standing orders for repeated blood and urine tests of military personnel and Indigenous communities at the test sites.

The language in some of the documents is unambiguous. One, from 1957, says that “all personnel selected for duty at Maralinga [the Australian test site] may be exposed to radiation”.

Many of the men have obtained their personnel and medical files – but say they have gaps that correspond to when they were stationed on the operations.

John Morris’s military medical file, for instance, is missing regular blood tests from Christmas Island that he says were part of the regime.

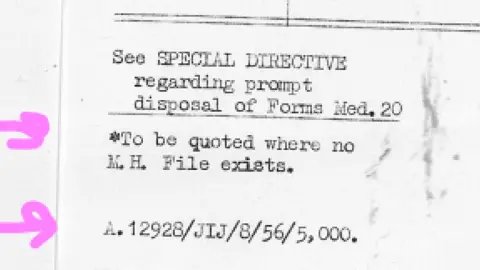

Then the campaign discovered, again by chance, what could be an official order to destroy medical records.

BBC/Hardcash Productions/Simon Rawles

BBC/Hardcash Productions/Simon RawlesThe widow of one veteran who had died of multiple cancers obtained her late husband’s personnel records, hoping the medical records would help with her claim for a war pension.

The bundle she received included a slip of paper, dated 1959, which marks where officials had removed pages. That was when her husband had been part of the testing programme.

And the slip says the material had been removed under a “special directive regarding prompt disposal”, on the then orders of the ministerial office for the Royal Air Force.

What was that “special directive”? Nobody knows.

So was there a cover-up decades ago?

A 2008 government filing, in one part of the then legal battle, shows officials assured their in-house lawyers that “no individual monitoring of servicemen” had taken place during the tests.

But that does not make sense given the Gledhill memo shows personnel were being tested – and men remember it, too.

Another government document, from the 1990s, shows officials discussing their “concerns” that judges at the European Court of Human Rights had been told that there were no classified records concerning the monitoring of personnel.

The men say something stinks, and they have relaunched their legal fight, but time – and age – is against them.

The men’s lawyers believe they have a case for a failure to disclose medical records and, at worst, may have had glimpses of a cover-up locked in the bowels of military archives.

If they sue, the case could take years that the men do not have. So they have proposed an alternative time-limited one-off tribunal to find answers.

And that is why the men now want to meet Sir Keir Starmer – to get it done.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn 2019, the Labour Party, then led by Jeremy Corbyn, pledged £50,000 for each surviving British nuclear-test veteran.

Sir Keir met the veterans in 2021 but made no promises – and the 2019 offer was not in the 2024 manifesto.

But the prime minister has pledged to introduce the so-called “Hillsborough law” that places a duty on public officials to come completely clean when faced with an allegation of cover-up or misconduct.

That law could be in force within a year and it could help the men get answers, assuming they are there to be found.

“Keir Starmer, meet us,” says John Morris. “All I want is to meet him and get a pathway forward. They have let me down for 70 years.”

Ministers ‘looking hard’ at veterans concerns

A Ministry of Defence spokesperson said it recognised the “huge contribution” of the veterans and the government was committed to working with them and “listening to their concerns”.

“Ministers are looking hard at the issue – including the question of records,” said the spokesperson.

“They will continue to engage with the individuals and families affected and as part of this engagement, the Minister of Veterans Alistair Carns has already met with parliamentarians and a Nuclear Test Veteran campaign group to discuss their concerns further.”

Both Labour and Conservatives governments have maintained no records have been withheld from the veterans, including from the court cases.

The MoD says research has found no link between the nuclear tests, ill health and genetic defects in children. That’s contradicted by a respected study from New Zealand that showed its personnel suffered genetic damage from attending the British tests.

BBC/Hardcash Productions/Simon Rawles

BBC/Hardcash Productions/Simon RawlesWhatever the government chooses to do, the impact of what the men witnessed will be with them forever.

When John Folkes was 19 years old, he was on board a plane ordered to fly through four atomic bomb mushroom clouds.

It was like being “microwaved”, he tells the BBC film, as his body was exposed to the raw power of a nuclear weapon. And he has suffered ever since from PTSD and a permanent tremble.

Some 14 months of his medical records are missing, despite him remembering radiation tests.

“It’s weighed heavily on my conscience,” the 89-year-old tells the BBC’s film.

“I’m a part of something that should never have happened.

“There exists within our society some dark forces that suppress the truth. I firmly believe that we’ve been betrayed. Shamefully betrayed.”

Britain’s Nuclear Bomb Scandal: Our Story airs on Wednesday 20 November at 21:00 on BBC Two and on iPlayer