South Korean president survives impeachment vote

Getty Images

Getty ImagesLawmakers in South Korea have narrowly failed to impeach the nation’s president over his short-lived attempt to declare martial law.

A bill to censure Yoon Suk Yeol fell three votes short of the 200 needed to pass, with many members of parliament in the ruling People Power Party (PPP) boycotting the vote.

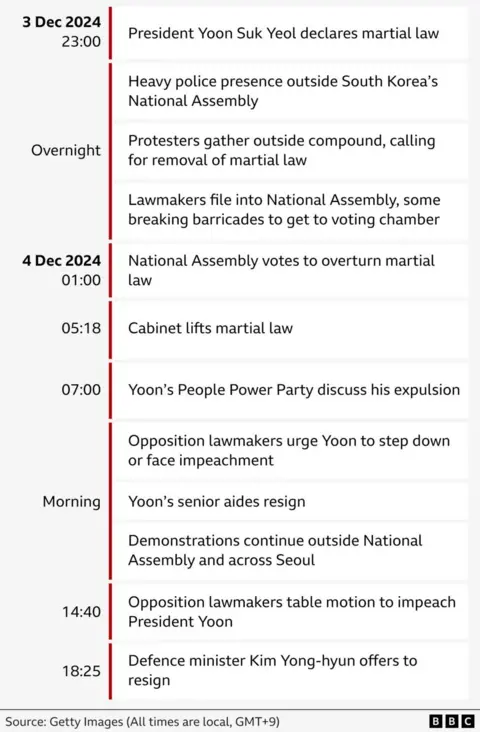

The South Korean premier sparked widespread shock and anger when he declared military rule – associated with authoritarianism in the country – on Tuesday, in a bid to break out of a political stalemate.

Yoon’s declaration was quickly overturned by parliament, before his government rescinded it a few hours later in the midst of large protests.

The impeachment bill needed a two-thirds majority in the National Assembly to pass, meaning at least eight PPP MPs would have to vote in favour.

However, all but three walked out of the chamber earlier on Saturday.

One of those who remained, Cho Kyung-tae, credited Yoon’s apology for the martial law decree on Saturday morning – after three days out of public view – as having influenced his decision not to back impeachment this time.

“The president’s apology and his willingness to step down early, as well as delegating all political agendas to the party, did have an impact on my decision,” he told the BBC ahead of the vote.

Cho said he believed impeachment would hand the presidency to the leader of the Democratic Party of Korea (DPK), Lee Jae-myung.

He added that Yoon’s “irrational and absurd decision” to declare martial law had “overshadowed” what he described as the DPK’s “many extreme actions” while in power.

Following Saturday’s vote, Lee insisted his party “will not give up” with its attempts to impeach Yoon, who he said had become “the worst risk” to South Korea.

“We will definitely return this country to normal by Christmas and the end of the year,” he told a crowd gathered outside the parliament in the capital, Seoul.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesPrior to Tuesday, martial law – temporary rule by military authorities in a time of emergency, during which civil rights are usually curtailed – had not been declared in South Korea since before it became a parliamentary democracy in 1987.

Yoon claimed the measures were needed to defeat “anti-state forces” in the parliament and referred to North Korea.

But others saw the move as an extreme reaction to the political stalemate that had arisen since the DPK won a landslide in April, reducing his government to vetoing the bills it passed, as well as Yoon’s increasing unpopularity in the wake of a scandal surrounding the First Lady.

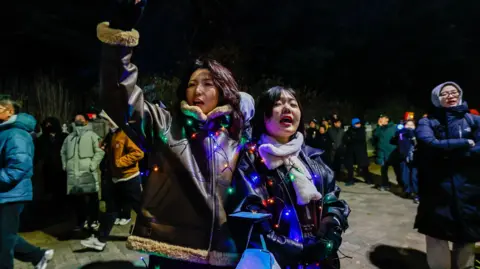

The president’s late-night address caused dramatic scenes at the National Assembly, with protesters descending en masse as military personnel attempted to block entry to the building.

Lawmakers tussled with the soldiers, with 190 MPs making it into the building to vote down the order.

In the early hours of Wednesday morning, Yoon’s cabinet rescinded the martial law declaration.

However, the short-lived military takeover has seen daily protests on the streets. Some came out in support of Yoon, though they were drowned out by angry mobs.

Authorities have since revealed more about the events of Tuesday night.

The commander charged with the military takeover said he had learned of the decree on TV along with everyone else in the country.

He said he had refused to make his troops arrest lawmakers inside parliament, and did not give them live ammunition rounds.

The National Intelligence Service later confirmed rumours that Yoon had ordered the arrest and interrogation of his political rivals – and even some of his supposed political allies, such as his own party leader Han Dong-hoon.

These revelations saw some members of Yoon’s own party signal their support for impeachment.

The president’s apology on Saturday morning appeared to be a last-ditch effort to shore up support.

He said the martial law declaration had been made out of “desperation” and pledged he would not make another.

Yoon did not offer to resign, but said he would leave decisions on how to stabilise the country to his party.

Were he to be impeached, it would not be unprecedented. In 2016, then-President Park Geun-hye was impeached after being accused of helping a friend commit extortion.

If South Korea’s parliament passes an impeachment bill, a trial would be held by a constitutional court. Two-thirds of that court would have to sustain the majority for him to be removed permanently from office.

Additional reporting by David Oh and Tiffanie Turnbull