Defendants face judgement for actions that led to beheading of French teacher

AFP

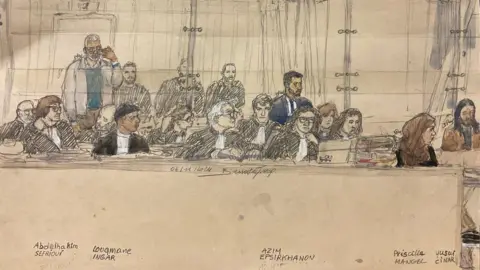

AFPEight people accused of abetting the jihadist murder of French teacher Samuel Paty are to learn their fate after a six-week trial in a Paris court.

They include the father of a schoolgirl whose lie about Paty’s alleged discrimination against Muslims in the classroom set in chain the events leading to his beheading on a street in October 2020.

Also on trial are a Muslim activist who led an online campaign against Paty, two boyhood friends of Chechen-born killer Abdoullakh Anzorov who allegedly helped him acquire weapons, and four radicalised men with whom he exchanged messages on social media.

Anzorov was shot dead by police minutes after killing the 47 year-old history-geography teacher outside his secondary school in the Paris suburb of Conflans-Saint-Honorine.

He was fired up by claims circulating on the internet that a few days earlier Paty had ordered Muslims to leave his class of 13-year-olds before revealing obscene pictures of the prophet Muhammad.

In fact Paty had been conducting a lesson on freedom of speech, and before showing one of the controversial images first published by Charlie Hebdo magazine, he advised pupils to avert their eyes if they feared being offended.

The schoolgirl, named as Z. Chnina, had not even been in class when this happened, but told her father she had been punished for raising an objection.

The trial has centred on legal arguments over whether people who in advance had no knowledge of the attack – or in some cases even of its perpetrator – could by their words nonetheless be guilty of “terrorist association”.

Summing up in court this week, prosecution lawyers asked for jail terms of between 18 months suspended and 16 years for the accused, saying their actions had indirectly led to the atrocity.

However, the prosecution had also angered members of Paty’s family by refusing to push for maximum sentences, and by downgrading the qualification of some of the imputed crimes.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDuring the trial, the court heard the first public testimony from the girl, Z. Chnina, now aged 17.

A year ago she was given a short suspended sentence for slander by a juvenile court, whose hearings were conducted behind closed doors.

“I want to apologise to all the [Paty family] because were it not for my lies they would not be here today,” she said, in sobs.

“And I want to apologise to my father because when he made the video it was partly because of my lie.”

In the days following Paty’s freedom-of-speech class, her father Brahim Chnina made videos denouncing the teacher by name. He also enlisted the help of activist Abdelhakim Sefrioui to spread the campaign through his social media network.

Chnina and Sefrioui never called for action against Paty, and they were unaware of the existence of Anzorov until the killing took place.

But for the prosecution they were nonetheless guilty of “terrorist association”, because they knew of the possible consequences of their campaign.

“No-one is saying they wanted the death of Samuel Paty, but in lighting 1,000 digital fuses they knew that one of them would lead to jihadist violence against the teacher,” according to prosecution’s submission.

The context in October 2020 was one of heightened tensions over jihadist violence, after Charlie Hebdo republished some of the controversial Muhammad cartoons. Five years earlier most of the staff of the magazine had been murdered in a jihadist gun attack at their Paris office.

This week in court the longest jail terms were requested for the two friends of Anzorov who accompanied him when he bought a knife and a fake gun. One of them also drove Anzorov to the school on the afternoon of the attack.

Neither of these defendants is a radicalised Muslim, and it was not established in court that they knew of Anzorov’s plans.

That was why the prosecution downgraded the charge against them from “complicity in a terrorist attack” which carries a possible life sentence.

The four other accused are people with whom Anzorov conversed on chatlines, again without him ever revealing his intention to kill Paty.

One of these, a convert to Islam called Priscilla Mangel, admitted making “provocative” remarks online about the Paty case but said she would never have made them had she known Anzorov’s intentions.

“For me this was an anodyne discussion with an anonymous person.”

For defence lawyers, none of the accused would have faced criminal proceedings for what they said, had it not been for the murder of Paty.

So the key legal question facing the court is whether utterances can become illegal depending on what follows.