‘It’s pure beauty’ – Italy’s largest medieval mosaics restored

Reuters

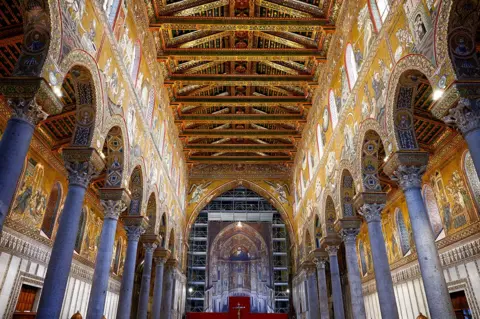

ReutersOn a hill overlooking the city of Palermo, in Sicily, sits a lesser-known gem of Italian art: the cathedral of Monreale.

Built in the 12th century under Norman rule, it boasts Italy’s largest Byzantine-style mosaics, second in the world only to those of Hagia Sophia in Istanbul.

Now, this Unesco World Heritage site has undergone an extensive restoration to bring it back to its former glory.

The Monreale mosaics were meant to impress, humble and inspire the visitor who walked down the central nave, following the fashion of Constantinople, the capital of the surviving Roman empire in the east.

They span over 6,400 square meters and contain around 2.2kg of solid gold.

Reuters

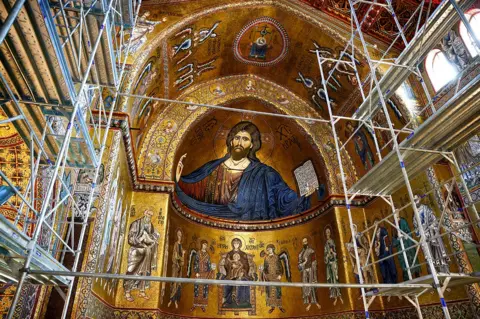

ReutersThe restoration lasted over a year, and in that time the cathedral was turned into a bit of a building site, with a maze of scaffolds set up on the altar and transept.

Local experts from the Italian Ministry of Culture led a series of interventions, starting with the removal of a thick layer of dust that had accumulated on the mosaics over the years.

Then they repaired some of the tiles that had lost their enamel and gold leaf, making them look like black spots from down below.

Finally, they intervened in the areas where the tiles were peeling off the wall and secured them.

Working on the mosaics was a challenge and a big responsibility, says Father Nicola Gaglio.

He has been a priest here for 17 years and has followed the restoration closely, not unlike an apprehensive dad.

“The team approached this work almost on their tiptoes,” he tells me.

“At times, there were some unforeseen issues and they had to pause the operations while they found a solution.

“For example, when they got to the ceiling, they realised that in the past it had been covered with a layer of varnish that had turned yellowish. They had to peel it off, quite literally, like cling film.”

Zumtobel

ZumtobelThe mosaics were last partly restored in 1978 , but this time the intervention had a much wider scope and it included replacing the old lighting system.

“There was a very old system. The light was low, the energy costs were through the roof and in no way it made justice to the beauty of the mosaics,” says Matteo Cundari.

He’s the Country Manager of Zumtobel, the firm that was tasked with installing the new lights.

“The main challenge was to make sure we’d highlight the mosaics and we’d create something that answers to the various needs of the cathedral,” he adds.

“We also wanted to create a completely reversible system, something that could be replaced in 10 or 15 years without damaging the building.”

Zumtobel

ZumtobelThis first tranche of works cost 1.1 million euros. A second one, focussing on the central nave, is being planned next.

I ask Fr Gaglio what it was like to see the scaffolding finally come off and the mosaics shine in their new light. He laughs and shrugs.

“When you see it, you’re overwhelmed with awe and you can’t really think of anything. It’s pure beauty,” he says.

“It’s a responsibility to be the keeper of such world heritage. This world needs beauty, because it reminds us of what’s good in humanity, of what it means to be men and women.”