Barbados fishing industry still reeling from hurricane aftermath

BBC

BBCThere are few clearer signs of the destructive power that Hurricane Beryl unleashed on Barbados in July than the scene at the temporary boatyard in the capital, Bridgetown.

Scores of mangled and cracked vessels sit on stacks, gaping holes in their hulls, their rudders snapped off and cabin windows broken.

Yet these were the lucky ones.

At least they can be repaired and put back out to sea. Many others sank, taking entire family incomes with them.

When Beryl lashed Barbados, the island’s fishing fleet was devastated in a matter of hours. About 75% of the active fleet was damaged, with 88 boats totally destroyed.

Charles Carter, who owns a blue-and-black fishing vessel called Joyce, was among those affected.

“It’s been real bad, I can tell you. I had to change both sides of the hull, up to the waterline,” he says, pointing at the now pristine boat in front of us.

It has taken months of restoration and thousands of dollars to get it back to this point, during which time Charles has barely been able to fish.

“That’s my living, my livelihood, fishing is all I do,” he says.

“The fishing industry is mash up,” echoes his friend, Captain Euride. “We’re just trying to get back the pieces.”

Now, six months after the storm, there are signs of calmer waters. On a warm Saturday, several repaired vessels were put back into the ocean with the help of a crane, a trailer and some government support.

Seeing Joyce back on the water is a welcome sight for all fishermen in Barbados.

But Barbadians are acutely aware that climate change means more active and powerful Atlantic hurricane seasons – and it may be just another year or two before the fishing industry is struck again. Beryl, for example, was the earliest-forming Category 5 storm on record.

Few understand the extent of the problem better than the island’s Chief Fisheries Officer, Dr Shelly Ann Cox.

“Our captains have been reporting that sea conditions have changed,” she explains. “Higher swells, sea surface temperatures are much warmer and they’re having difficulty getting flying fish now at the beginning of our pelagic season.”

The flying fish is a national symbol in Barbados and a key part of the island’s cuisine. But climate change has been harming the stocks for years.

At the Oistins Fish Market in Bridgetown, flying fish are still available, along with marlin, mahi-mahi and tuna, though only a handful of stalls are open.

At one of them, Cornelius Carrington, from the Freedom Fish House. fillets a kingfish with the speed and dexterity of a man who has spent many years with a fish knife in his hands.

“Beryl was like a surprise attack, like an ambush,” says Cornelius, in a deep baritone voice, over the market’s chatter, reggae and thwack of cleavers on chopping boards.

Cornelius lost one of his two boats in Hurricane Beryl. “It’s the first time a hurricane has come from the south like that, normally storms hit us from the north,” he said.

Although his second boat allowed him to stay afloat financially, Cornelius thinks the hand of climate change is increasingly present in the fishermen’s fate.

“Right now, everything has changed. The tides are changing, the weather is changing, the temperature of the sea, the whole pattern has changed.”

The effects are also being felt in the tourism industry, he says, with hotels and restaurants struggling to find enough fish to meet demand each month.

For Dr Shelly Ann Cox, public education is key and, she says, the message is getting through.

“Perhaps because we are an island and we’re so connected to the water, people in Barbados can speak well on the impact on climate change and what that means for our country,” she says.

“I think if you speak to children as well, they’re very knowledgeable about the topic.”

To see for myself, I visited a secondary school – Harrison College – as a member of a local NGO, the Caribbean Youth Environmental Network (CYEN), talked to members of the school’s Environmental Club about climate change.

The CYEN representative, Sheldon Marshall, is an energy expert who quizzed the pupils about greenhouse gases and the steps they could take at home to help reduce carbon emissions on the island.

“How can you, as young people in Barbados, help make a difference on climate change?” he asked them.

Following an engaging and lively debate, I asked the pupils how they felt about Barbados being on the front line of global climate change, despite having only a small carbon footprint itself.

“Personally, I take a very pessimistic view,” said 17-year-old Isabella Fredricks.

“We are a very small country. No matter how hard we try to change, if the big countries – the main producers of pollution like America, India and China – don’t make a change, everything we do is going to be pointless.”

Her classmate, Tenusha Ramsham, is slightly more optimistic.

“I think that all great big leaps in history were made when people collaborated and innovated,” she argues. “I don’t think we should be completely disheartened because research, innovation, creating technology and education will ultimately lead to the future that we want.”

“I feel if we can communicate to the global superpowers the pain that we feel seeing this happen to our environment,” adds 16-year-old Adrielle Baird, “then it would help them to understand and help us collaborate to find ways to fix the issues that we’re seeing.”

For the island’s young people, their very futures are at stake. Rising sea levels now pose an existential threat to the small islands of the Caribbean.

It is a point on which the Prime Minister of Barbados, Mia Mottley, has become a global advocate for change – urging greater action over an impending climate catastrophe in her speech at COP29 and calling for economic compensation from the world’s industrialised nations.

On its shores and in its seas, it feels like Barbados is under siege – dealing with issues from coral bleaching to coastal erosion. While the impetus for action comes from the island’s youth, it is the older generations who have borne witness as the changes unfold.

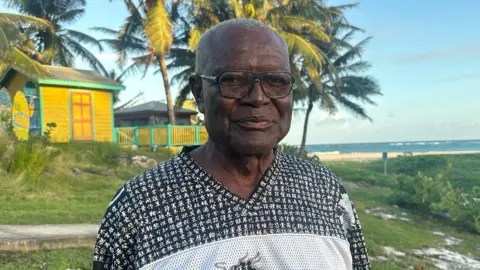

Steven Bourne has fished the waters around Barbados his whole life and lost two boats in Hurricane Beryl. As we look out at the coastline from a dilapidated beach-hut bar, he says the island’s sands have shifted before his very eyes.

“It’s an attack from the elements. You see it taking the beaches away, but years ago you’d be sitting here, and you could see the water’s edge coming upon the sand. Now you can’t because the sand’s built up so much.”

By coincidence, in the same bar where I chatted to Steven was Home Affairs Minister Wilfred Abrahams, who has responsibility for national disaster management.

I put it to him that it must be a a difficult time for disaster management in the Caribbean.

“The whole landscape has changed entirely,” he replied. “Once upon a time, it was rare to get a Category Five hurricane in any year. Now we’re getting them every year. So the intensity and the frequency are cause for concern.”

Even the duration of the hurricane season has changed, he says.

“We used to have a rhyme that went: June, too soon; July, standby; October, all over,” he tells me. Extreme weather events like Beryl have rendered such an idea obsolete.

“What we can expect has changed, what we’ve prepared for our whole lives and what our culture is built around has changed,” he adds.

Fisherman Steven Bourne had hoped to retire before Beryl. Now, he says, he and the rest of the islanders have no choice but to keep going.

“Being afraid or anything like that don’t make no sense. Because there’s nowhere for we to go. We love this rock. And we will always be on this rock.”