The driver who ‘jumped’ his bus over the Tower Bridge gap

On 30 December 1952, a double-decker bus drove on to Tower Bridge on its usual route between Shoreditch and Dulwich.

It was late in the evening, dark and the temperature had dipped below freezing.

It was a couple of weeks after the great smog had brought London to a standstill, and although that particularly foul miasma had dispersed, smog still regularly reduced visibility.

The traffic lights were green, there was no ringing of a warning hand-bell.

Albert Gunter, the driver, travelling at a steady 12mph (19km/h), proceeded on to the bridge.

Then he noticed the road in front of him seemed to be falling away.

He, his bus, its 20 passengers and one conductor were on the edge of the southern bascule – a movable section of road – which was continuing to rise.

It was too late to go back, too late to stop.

So the former wartime tank-driver dropped down two gears, and slammed his foot on the accelerator.

Reuters

ReutersMr Gunter spoke to Time magazine and his interview was published in its “foreign news” section on 12 January 1953.

“Everything happened terribly quickly,” he told Time. “I realised that the part we were on was rising. It was horrifying. I felt we had to keep on or we might be flung into the river.”

One of the passengers, Peter Dunn, said: “Before we knew it, we were going across Tower Bridge – but just as we had gone over the first half of the section that goes up, there was a loud crashing sound and I was thrown on to the floor.”

The superintendent engineer of the bridge said the bus had “sufficient speed to bridge the gap, but the rear wheels must have fallen with quite a jolt”.

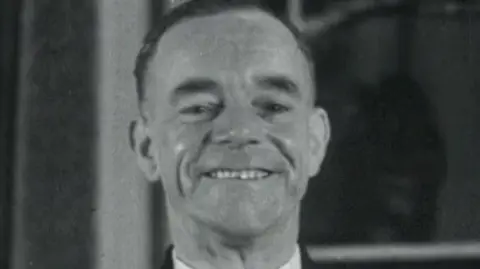

ANL/Shutterstock

ANL/ShutterstockEverything was unclear to Mr Dunn, jumbled with other passengers on the floor, until the bus came to a halt.

And then Mr Gunter “came round to invite us to have a look at the gap”.

Passengers, conductor and driver duly filed off the bus to have a look.

Mr Dunn continued: “The driver then told us that as he started to drive across the opening part of the bridge, he realised that the side that the bus was on was going up.

“He said he could only think of two options as to what to do – one was to stop the bus and hope someone would realise what was happening and stop it [the bascules being opened], but that left the possibility of the bus slipping and perhaps toppling into the river; the other was to continue driving and to ‘jump’ the gap.

“He said that he had been a tank-driver during the war and that a tank would have had no trouble getting on to the other side and decided to see if a double-decker could do the same.

“So, thanks to his quick thinking, we were all delivered safe to the other side.”

ANL/Shutterstock

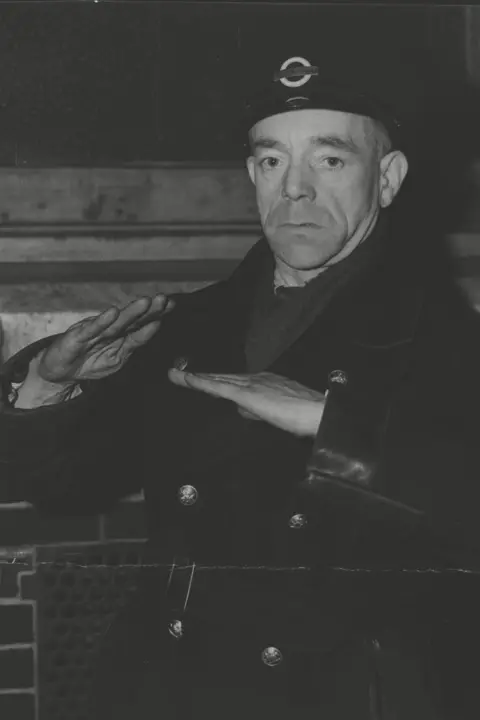

ANL/ShutterstockNobody on the bus was seriously physically injured – one broken leg for the conductor and one fractured collarbone for a passenger – although all were, obviously, shaken.

One young woman though, found it difficult to resume normal life, as she was too distressed by the incident to board another bus.

May Walshaw, who was one of the people flung to the front of the vehicle, regained her nerve after Mr Gunter helped.

She got on the No. 78, with Mr Gunter driving, and together, they crossed Tower Bridge once more.

In September 1953, Miss Walshaw became Mrs MacDonald – and Mr Gunter, by now a firm friend, was at the wedding.

Getty Images

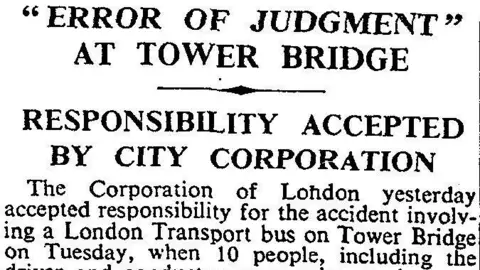

Getty ImagesAs the Daily Mail reported on 3 January, four days after the incident: “The main question people were asking today was ‘why did it happen?'”

Why indeed?

The normal warning signals given to traffic when a lift was imminent were red traffic lights and the ringing of a hand-bell by a bridge operator.

The day after the incident, Mr Gunter said the lights had been green and there was no bell.

A City Police inspector insisted that the usual warning signals were given.

The Times archive

The Times archiveAfter a brief inquiry, the Corporation of London accepted responsibility for the accident.

The Bridge House Estates Committee, which owns and is responsible for the maintenance of several bridges over the Thames, stated “it appeared that the accident was attributable to an error of judgment on the part of the responsible employee at the bridge”.

It added: “The committee will have a report made to them on the incident and will consider whether any further steps should be taken.”

As a reward from London Transport, Mr Gunter was given £10 (the equivalent of about £350 today) and a day off.

He was awarded the cash at a ceremony, and when asked what he would do with the bonus, he said “five for me and five for the missus”.

Mr Gunter later received a reward of £35 from the City Corporation, and a week’s holiday in Bournemouth. His children were invited to the Lord Mayor’s children’s party.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesTower Bridge opened in 1894, eight years after construction work began. It was originally designed to be a sort of drawbridge, which require ropes or chains to pull up the road. But Tower Bridge’s roads were too heavy to be opened in that way, so it is instead a bascule bridge, in which the roads move like a seesaw and pivot.

It was built because the city needed a bridge downstream from London Bridge without disrupting river traffic.

Opening and closing is done with eight large cogs, 1m in diameter, four on each side, which rotate.

The power required to rotate the cogs was initially supplied by steam and then, after 1976, by electricity.

The bridge was made with caisson foundations – prefabricated hollow substructures designed to be placed on or near the surface of the ground, sunk to the desired depth and then filled with material to weigh it down.

Listen to the best of BBC Radio London on Sounds and follow BBC London on Facebook, X and Instagram. Send your story ideas to hello.bbclondon@bbc.co.uk