Why wildfires are becoming faster and more furious

Getty Images

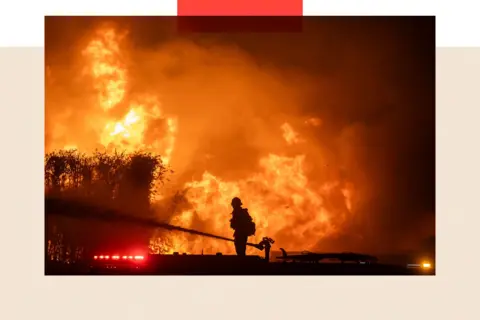

Getty ImagesIt was terrible timing. In the late morning of Tuesday 6 January, a “life-threatening and destructive” windstorm was heading for the northern suburbs of Los Angeles. The local office of the US National Weather Service published a strongly worded alert at roughly 10:30am local time. At almost that exact moment, a fire erupted in the Palisades neighbourhood of LA.

“The fire was able to get started, get a foothold, and then the wind came in and pushed it really, really hard,” says Ellie Graeden, co-chief executive of RedZone Analytics, which makes wildfire modelling products for the insurance industry. “This is really as bad as it can get.”

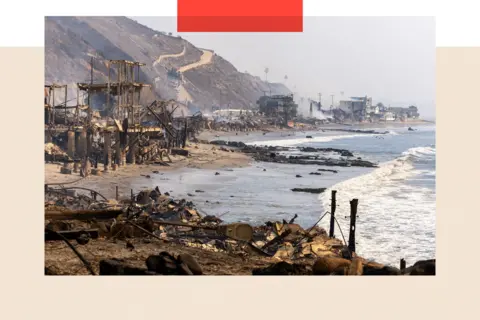

The fire exploded, followed by other wildfires in nearby areas. Thousands of homes and other buildings have been razed. Sunset Boulevard is in ruins. At the time of writing, LA’s fires have killed at least 10 people. Officials have ordered nearly 180,000 people to evacuate.

The fires now rank as the most destructive fires in LA’s history, with some estimates of the damage put at between $52bn-57bn (£42bn-£46bn).

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWe still don’t know why they started, however. It might have been a lightning strike, downed power lines, a carelessly discarded cigarette. There could be a more nefarious reason, arson. Most wildfires are caused by humans.

But as the LA authorities begin to piece together what initially sparked the blazes, the speed with which those first flames became raging, rapidly spreading infernos is symptomatic of something happening far more widely.

‘A really explosive situation’

In the case of the LA fires, a confluence of environmental conditions came together with devastating timing. A combination of long-term drought and heavy rainfall in the days before provided the fuel, while powerful – and at times hurricane-force – winds fanned the fires into raging infernos.

At the outset, the Santa Ana winds as they are known – strong and gusty winds that blow from inland towards the coast – reached speeds of 80mph (129km/h), supercharging the inferno.

Disastrously, the high winds prevented some firefighting helicopters and planes from taking to the skies in order to dump water on the burning areas.

“Without that air support, we’re basically playing whack-a-mole to prevent losses at specific points,” says Ms Graeden.

These conditions come against the backdrop of climate change, which is not only increasing the risk of wildfires around the world, but also making them particularly explosive. This is when relatively small blazes rapidly “blow up” so suddenly and with such ferocity that they become difficult to control.

Shutterstock

ShutterstockIn California, the risk of such extremely fast-growing fires has increased by an estimated 25% due to human-caused climate change, according to some models.

Rising temperatures and prolonged periods of drought are stripping vegetation and dead plant material of their moisture, meaning when a fire does start, there can be no stopping it.

The situation is nothing short of “harrowing”, says Matt Jones, an Earth system scientist at the University of East Anglia, who studies the impact of climate change on wildfires. He notes that, in 2022 and 2023, LA received extraordinary amounts of rain – 52.46in (133cm) of precipitation hit downtown LA during this period, which was nearly a record.

That excessive rain helped plants in the area to grow but then, in 2024, the weather changed. Last year was extremely dry in contrast to the previous two years. It means that there is currently a large volume of dried-out vegetation scattered around southern California.

“We’re left with a really explosive situation,” says Mr Jones.

Fire and wind: the Santa Ana effect

There was also the significant influence of the windstorm. The Santa Ana winds go by various names, depending on where you live. Known as the Föhn or Föhnwind in the Alpine regions of Germany, Austria and Switzerland, they are associated in folk belief with a range of symptoms including migraines, depression, sleeplessness, confusion, and increased risk of accidents.

One account published in a scientific journal in 1911 reveals the dramatic effects of the Föhnwind in Innsbruck, Austria: “This wind often blows with great violence, and unless one’s windows are promptly closed everything in the house is speedily covered with a thick layer of dust.”

Climate change is creating hotter conditions in some locations where Santa Ana-like winds occur, meaning that the impact or potential consequences – especially in terms of rapidly escalating wildfires – is worsening.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAccording to some research, these winds are becoming more common in parts of the world due to climate change.

The effect on wildfires of such an increase could be profound. In Switzerland, for example, researchers found Föhn winds led to fires burning three times as much area than on days where there were no such winds.

Fires that spread very quickly are particularly dangerous – not just because of the threat to human life and property, but also because of how widespread those fires can become.

Research published last year examined the frequency of “blow up” fire events that suddenly escalate. Notably, it was areas where fires burned intensely for relatively short periods of time that ended up burning larger areas overall. “Single-day extreme fire spread events are disproportionately shaping North American landscapes,” the authors wrote.

This makes sense, says Mr Jones: “If a fire is escalating quickly, generally speaking it means you’ve got very dry fuels and potential for extreme fire behaviour.”

The study authors also estimated that, between 2002 and 2021, North American fires that burned more than 1,704 hectares (4210 acres) in a single day burned an average of 2.3 million hectares (5.7 million acres) annually overall. Mediterranean California, where LA is located, is especially prone to rapidly escalating, wide-burning fires, according to the study.

Wildfires ‘make their own weather’

While the downslope Santa Ana winds appear to have accelerated the LA wildfires, very different conditions can also cause fires to blow up. In the absence of powerful winds, wildfires can sometimes make their own weather, says Mr Jones.

“They generate their own, strong, localised winds, which can affect both the pace at which the fire spreads but also trigger erratic directional changes,” he explains.

As a blaze heats the air above it, it can create updrafts powerful enough to form huge pyrocumulative clouds in the sky above. The appearance of such a cloud can indicate that a wildfire is about to escalate rapidly, or that this process has already begun, research published in 2021 found.

Such storm clouds can cause lightning strikes, which could ignite yet more fires nearby.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThis interplay of wind and fire is a common theme. “You can, in certain parts of the globe, get a rapidly growing fire during [the] passage of a front – a weather system that basically gives you the wind but doesn’t bring you the precipitation,” explains John Abatzoglou, professor of climatology at the University of California, Merced.

Fires tend to run up hillsides in the absence of Santa Ana winds, says Prof Abatzoglou, though in places like California, the Santa Ana winds can push fires down hills instead. Similar downslope winds were also thought to have played a role in the deadly Maui wildfires in Hawaii in 2023.

In either case, fast-developing fires are very problematic when they occur near towns and cities. “Within a matter of hours from ignition you had huge numbers of people that were impacted,” says Prof Abatzoglou, referring to the situation in LA.

Lessons from the Getty Villa

A controversial question, especially in highly populated places such as California, is whether it is still safe to live in such close proximity to areas prone to these disasters.

Insurers have gradually backed away from the state in recent years, cutting the number of policies available to homeowners, though last month the California Department of Insurance issued a landmark regulation that aimed to make insurance more accessible.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSome residents have also been looking into ways to attempt to fireproof their homes.

Those with the greatest resources might take inspiration from the Getty Villa, a museum in the Pacific Palisades. (Though perhaps not without irony. The museum was originally built by J Paul Getty, an early 20th-Century oil tycoon.)

Staff routinely trim trees and shrubs in the gardens to ensure there is not an excess of vegetation available to provide fuel for fires. The building’s galleries also have double walls and staff can control, to some extent, the flow of hot air into the villa via the air conditioning system.

But the fact that fires can leapfrog for several miles makes containment difficult. Embers from burning vegetation can be whipped up and carried by the wind, allowing new fires to ignite some distance away. Rather than catching fire from direct contact with flames, many homes begin to burn due to embers that can fly miles, entering through eaves or gable vents.

Homeowners can replace porous vents with fire-resistant ones designed to keep out windswept embers, and install ember-resistant gutter guards that allow rainwater but stop vegetation from piling up on the roofline.

Despite the grandeur of some LA mansions, however, many were left ravaged by the recent fires – including multiple homes belonging to celebrities. The biggest wildfires could likely overwhelm even the most fortified properties.

Fireproofing: from grazing goats to supercomputers

LA does try to reduce the risk of gigantic fires taking hold. The city rents goats, for instance, so that the animals can graze brush from hillsides.

“The reception is overwhelmingly positive wherever we go,” goat herder Michael Choi said in a recent interview. “It’s a win-win scenario as far as I can tell.”

There are also efforts to use high-tech camera-based surveillance systems to watch for developing wildfires, and supercomputers that try to predict when fires are most likely to occur. That said, these systems were in place in LA last week but that did not stop the latest fires claiming lives and leaving vast areas in ruins.

Homeowners who live in wildfire-prone locations need to think about their own vulnerability, says Ms Graeden: “This is a risk that is not necessarily seasonal anymore. This is the type of risk that people need to be taking very seriously at all times.”

She recommends clearing as much vegetation from around residential properties as possible, and installing a fire-resistant roof or a sprinkler system. Having an evacuation plan in place could also save lives.

When efforts to repair and rebuild homes in LA eventually get underway, it is possible some may turn to fire-resistant materials such as bricks made of earth.

Reuters

ReutersBut at the heart of it is a deeper question. “We built civilisation that [functions] in one climate and now we are, through burning fossil fuels, fundamentally changing [that climate],” argues Margaret Klein Salamon, a climate activist and leader of the Climate Emergency Fund, a non-profit that funds climate activism.

“This is what the future looks like unless we make drastic changes,” she adds, arguing that the problem of climate change will not go away simply by relocating from some of the worst-affected places.

- Five images that explain why the LA fires spread so fast

- The goats fighting fires in Los Angeles

- ‘I have nothing to go back to’ – fires heartbreak

As the world gets hotter, and as rainfall patterns become more erratic, we may see fires like those in LA erupt with increasing frequency. Abatzoglou highlights the 2024 wildfires in Chile and Greece as key examples in which very dry conditions set the stage for catastrophe.

In 2023 fires hit Canada and burned an area larger than England – these were also fuelled by high temperatures and drought.

Climate change brings dangerous variability, notes Abatzoglou. That swing in weather we’ve seen in southern California, from a period of heavy rainfall to suddenly hot, dry, fire-sparking conditions – known as “hydroclimate whiplash” – is clearly very problematic.

“It’s really these sequences that I think are important when it comes to fire,” says Abatzoglou.

“Rapid swings between unusually wet to unusually dry conditions. That’s something we are seeing across the globe.”

BBC InDepth is the new home on the website and app for the best analysis and expertise from our top journalists. Under a distinctive new brand, we’ll bring you fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions, and deep reporting on the biggest issues to help you make sense of a complex world. And we’ll be showcasing thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. We’re starting small but thinking big, and we want to know what you think – you can send us your feedback by clicking on the button below.