Trapped in the dark for 35 hours – Red Sea dive-boat survivors tell of terrifying escapes

BBC

BBC“By the end, I was just wondering how I would prefer to die.”

Spending 35 hours trapped in a pitch-black air pocket in the upturned hull of a boat has taken its toll on Lucianna Galetta, her voice cracking as she recounts her ordeal.

A video she managed to film briefly on her phone, now shared with the BBC, shows the space where she thought her life might end – and how surging sea water and floating debris prevented her escape.

Lucianna was the last of 35 survivors to be rescued from the wreck of the Sea Story, an Egyptian dive vessel that sank in the Red Sea on 25 November last year. Up to 11 people died or are still missing, including two Britons, Jenny Cawson and Tarig Sinada from Devon.

At the time, Egyptian authorities attributed the disaster to a huge wave of up to 4m (13ft), but the BBC has spoken to 11 survivors of the Sea Story who have cast doubt on the claim. That has been supported by a leading oceanographer, who told us weather data from the time suggests a wave could not have been responsible, and that a combination of crew error and failings in the boat were the likely cause.

As well as describing the terror of being trapped in a rapidly sinking boat, the survivors accuse the company which ran it, Dive Pro Liveaboard, of several safety failings. They also say the Egyptian authorities were slow to react, something which may have cost lives. We have put questions to Dive Pro Liveaboard – based in Hurghada – and the Egyptian government, but not received any reply.

This, for the first time, is the inside story of how the Sea Story sank, as told by those who made it out alive.

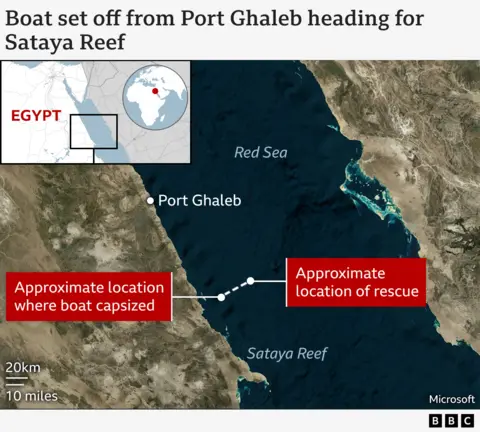

The luxury dive boat set off from Port Ghaleb on Egypt’s Red Sea Coast on 24 November. On board were 31 international guests – mostly experienced divers – and three dive guides, along with 12 Egyptian crew. They were on a six-day trip, with their first destination being Sataya Reef, a popular diving spot.

Like many of those on board, Lucianna’s first impressions of the Sea Story were positive. “It looked like a really nice boat, very big, very clean,” she says, speaking from her home in Belgium.

The company had transferred over Lucianna and others at the last minute from another boat, which had hundreds of good online reviews. Several guests were told they were getting an “upgrade” but some were frustrated because it was not going to the destination they had booked.

Conditions that night were quite rough, although the survivors we spoke to, including experienced sailors, say the boat seemed more unstable than they would have expected.

At one point, a few hours before the capsizing, a small inflatable boat slipped off the back of the Sea Story. A passenger filmed as the crew battled to bring it back on board – the oceanographer the BBC spoke to says the video shows conditions which were not unusual and consistent with 1.5m (5ft) waves.

“Looking out at the waves, the weather wasn’t terrible,” says Sarah Martin, an NHS doctor from Lancaster who was on the trip. But, she says, “furniture was sliding around the deck – we asked the crew if it was normal and they just shrugged, so we didn’t realise the danger we were in”.

“I didn’t sleep that night because the boat was rocking so much,” says Hissora Gonzalez, a diver from Spain, whose cabin was on the lower deck.

She describes how the boat rolled sharply several times until, just before 03:00, it flipped onto its side with a loud bang, followed by silence as the engines died – and total darkness.

Shouting could soon be heard coming from other cabins, as people were thrown from their beds. Possessions were scattered around, blocking exits and making escape difficult. One survivor – who had been sleeping outside on deck – described being trapped under heavy furniture which had shifted as the boat rolled.

Hissora Gonzalez

Hissora Gonzalez“We couldn’t see anything. I didn’t know if I was walking on the floor, on the ceiling, on the side,” says Hissora. Disoriented, she started looking around for life jackets. Before she could find one, her friend Cristhian Cercos shouted at her to run.

That call may well have saved her life. Their cabin was on the starboard (right) of the boat, the side that hit the sea. Nearly all of the dead or missing had cabins on that side of the boat.

“I could hear the water coming in, but I could not see it,” says Hissora. Their cabin door was now on the ceiling – she only escaped because Cristhian pulled her up on the fifth attempt.

Across the hall from Hissora, also in complete darkness, were Sarah and her cabin mate Natalia Sanchez Fuster, a dive guide. They couldn’t find the handle to the cabin door. When Sarah managed to turn on the torch on her phone she realised “everything was at 90 degrees – the door was on the floor and all our things were blocking it”.

After clearing the doorway, they joined about 10 others heading for an emergency exit towards the bow (front) of the boat.

Sarah Martin

Sarah MartinWith the boat on its side, the group had to crawl along the emergency staircase for two floors, past the restaurant and dining room on the main deck. It was hard to find their way and it seemed the contents of the kitchen cupboards had spilled out over the floors.

“We had to climb along door frames and beams to make our way out,” says Sarah. “It was quite disorienting in the dark and it was very slippery. There was cooking oil and broken eggs everywhere.”

Hissora, just ahead of Sarah, managed to make it to the upper deck. She could hear people screaming behind her but did not turn around. “I was afraid of looking back and seeing all the water coming in,” she says.

By this time, the Sea Story was sinking fast. Those who had reached the top deck knew they would have to jump into the water – a 2-3m (7-10ft) drop.

“I was paralysed because Cristhian kept saying to me ‘don’t jump’ because he could see someone was trying to release the life raft,” Hissora recalls.

Sarah was behind Hissora and desperate to get out. “There were other guests holding on to the side, blocking the exit,” she remembers. “We were shouting at them to move out of the way.”

With the water rising fast, Hissora, Sarah and the dozen or so people who had reached the top deck jumped into the water. They knew the danger was not over yet. “If the boat was going down, we needed to get away so it wouldn’t pull us down with it,” says Sarah.

Natalia, who had also jumped in, swam around the boat – she heard people screaming from inside the cabins and tried to use floating debris to break the windows, but didn’t succeed.

Sarah and Natalia were among the few who had grabbed a life jacket before escaping, but Sarah says they were not functioning as they should have.

“We noticed the lights weren’t working. Looking back, I don’t think there were any batteries in there.”

It is just one of several safety failings reported by the people we interviewed.

In total, we have spoken to seven of the survivors who had been staying on the lower deck. They all tell a near-identical story of the moment the boat went over – but not all of them escaped the same way.

Lucianna Galetta was in a cabin towards the back of the lower deck with her partner Christophe Lemmens. They were just moments slower than the others in realising the danger. That delay cost them dearly.

“We started to get up and tried to find the life jackets,” says Lucianna. “We opened the door but there was already water in the corridor. I think we panicked as we jumped in and almost drowned.”

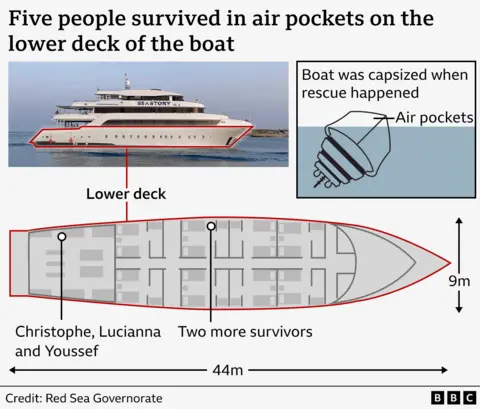

Unable to reach the exit at the front, Lucianna and Christophe ended up in an air pocket in the engine room at the stern (rear) of the boat, which was still sticking out of the water. They did not understand where they were until they were joined in the tiny space, some time later, by one of the dive instructors, Youssef al-Faramawy.

The three of them would stay there, sitting on fuel tanks, for about 35 hours.

Outside the boat, Sarah, Hissora and the others who had jumped off eventually found the two life rafts, which had deployed after the sinking. As they clambered on board, they saw the boat’s captain and a number of other crew members were already there.

“There should be some supplies in here,” Sarah remembers one of the other guests saying. All the people we spoke to recall a safety briefing mentioning that the life rafts had food and water in them – but they did not, the BBC were told.

“We found a torch, but again it didn’t have any batteries. We didn’t have any water or any food,” Sarah says. “There were flares, but they had already been used.”

Sarah also says of the three blankets on board the raft, one had been taken by the captain for himself, leaving one for the rest of the crew and another for the guests. “We ripped it up and huddled together,” says Sarah.

The rafts were met by rescue vessels at about 11:00 on the morning of 25 November, about eight hours after the capsizing. Both they, and the boat, had drifted eastwards.

Back on board the Sea Story, Lucianna heard the rescue helicopter – but her ordeal was far from over.

“At this time we were very happy, but we had to wait 27 hours more,” she says.

Despite the boat having been located, the rescue effort was slow to reach them. “We had no communication with the outside, nothing. No-one tried to see if there was someone alive in there,” Lucianna says.

She tells me there were moments when darkness and despair overtook her. “I was so ready to die. We didn’t think that someone would come.”

After several hours trapped in the air pocket, the dive guide, Youssef, wanted to try to swim through the boat, but Lucianna and Christophe persuaded him not to. “Stay with us because they are going to come to get our bodies, so they will find us,” Lucianna recalls telling him.

Eventually, after nearly a day and a half stuck in the hull of the Sea Story, a light appeared in the darkness.

A local Egyptian diving instructor, Khattab al-Faramawi, who was Youssef’s uncle, had braved the wreck, diving through the submerged corridors looking for people. He took Youssef out first, then, after another hour’s delay because of issues with the breathing apparatus, returned to lead Lucianna and her partner to safety. “I hugged him so hard,” says Lucianna. “I was very, very happy.”

In total, five people from the Sea Story were rescued by divers, including a Swiss man and a Finnish woman who had survived in another air pocket inside their cabin on the lower deck. Four bodies were recovered.

But Lucianna is critical of the fact the Egyptian navy had to rely on volunteers. “We waited 35 hours. I don’t understand how there are no divers on the Egyptian military boats.”

Lucianna, Christophe and Youssef were taken on board a waiting naval vessel, before returning to shore. They were the last to be rescued. At least 11 people either died or are missing, presumed dead.

Among them are Jenny Cawson and Tarig Sinada, a couple from Devon who were staying on the main deck, on the side of the boat that hit the water. Their bodies have never been found.

“It doesn’t feel like it’s real,” says Andy Williamson, a friend of the couple. “We keep expecting them to walk through the door.” A month and a half after the sinking, hopes of that happening have all but vanished.

The couple were experienced divers who always carefully researched the safety record of boats before their trips. They were also switched on to the Sea Story at the last minute, something that may have ultimately cost them dearly.

The BBC spoke to survivors from nearly every cabin on the vessel in which someone got out alive. They all confirm the boat sank between 02:00 and 03:00. However, according to local authorities, a distress signal was not received until about 05:30 – a further factor which may have cost lives.

Five survivors also reported that the heavy furniture on the top deck was unsecured and moved around before the sinking. The woman who had been sleeping on deck believes it all shifting to one side, as the boat started to overturn, further destabilised the Sea Story.

The narrative put forward by Egyptian officials in the immediate aftermath, reported by news agencies around the world, was that a huge wave hit the boat. Multiple survivors’ experiences in the water, just minutes after the capsizing, casts doubt on that.

“When we were in the water, the waves weren’t so big that we weren’t able to swim in them,” says Sarah, “so it does leave us wondering why that boat sank.”

Those suspicions are supported by data.

Handout

HandoutDr Simon Boxall is a leading oceanographer from the University of Southampton. He has analysed the weather from the day which shows the biggest waves were about 1.5m (5ft) – so he says “there is no way a 4m (13ft) wave could have occurred in that region, at that time”.

The Egyptian Meteorological Authority had warned of high waves on the Red Sea and advised against maritime activity on 24 and 25 November. But, according to Dr Boxall, “these were over 200km (120 miles) away to the north of where the vessel went down.”

He says that leaves only two options, either pilot error or an error in the design of the vessel – or a combination of both.

The UK’s Marine Accident Investigation Board (MAIB), which will shortly publish a safety bulletin into the sinking, has recently warned divers of safety issues in the Red Sea after a number of incidents – at least two of which involved the same company, Dive Pro Liveaboard.

The BBC sent all the safety concerns raised in this article to the Egyptian government and the company, Dive Pro Liveaboard, multiple times. We are yet to receive a response from either.

After the disaster, the Egyptian authorities immediately opened an investigation into the sinking. That is yet to report, but for the friends of Jenny and Tarig this is about more than one boat.

“We’ve unfortunately had to learn of the dangers of diving in Egypt in the most tragic of circumstances,” says Andy Williamson. “I don’t know how we will ever get over this.

Lucianna wants to understand exactly what went wrong. “We are lucky to be alive,” she says. “But there are so many people who didn’t come back from this and I want their families to be able to grieve.”

On Wednesday, the survivors tell the BBC about what happened to them after they had been rescued – and the questions they now have about the official investigation.