The enduring controversy over the Lockerbie bombing

PA Media

PA MediaThe first of two TV dramas on the Lockerbie disaster to be broadcast this year will, for many people, be their first glimpse into this labyrinth of a case.

Based on a book by the father of one of the victims, Lockerbie: A Search for Truth focuses on longstanding claims that the only man found guilty of bombing Pan Am 103 was innocent.

The production – which has provoked fierce criticism from relatives of American victims – does not mention that the conviction of Abdulbasset Al Megrahi for murdering 270 people was upheld twice on appeal.

Each episode of the Sky Atlantic series starts with a declaration that it’s “inspired by the work and research” of Dr Jim Swire, whose daughter Flora was on board Pan Am 103 when it broke apart over Lockerbie in December 1988.

Flora Swire was one of 259 passengers and crew who were killed along with 11 residents in Lockerbie when the wreckage destroyed their homes.

In 2001, after an eight-month trial, Scottish judges convicted Megrahi of bombing the plane while acting with other members of the Libyan intelligence service.

For more than 20 years, Jim Swire and his supporters have argued that Megrahi and Libya were framed for political expediency.

They believe the real culprits were Iran and a Syrian-backed group, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine General Command (PFLP-GC).

Relatives of other victims dismiss that as a baseless conspiracy theory.

Later this year, the case will be examined all over again when another Libyan suspect goes on trial in Washington, accused of building the Lockerbie bomb.

The warnings before the bombing

The controversy over Lockerbie began within days of the tragedy on 21 December 1988.

As the drama recounts, it soon emerged that there had been warnings that a bomb attack on a Pan Am flight was imminent.

Those warnings had not been made public. The passengers, including a CIA agent, boarded Pan Am 103 without knowing anything about them.

The US president Ronald Reagan said afterwards: “Such a public statement with nothing more to go on than an anonymous phone call, you would literally have closed down the air traffic in the world.”

In a BBC documentary in 2008, the government official who took that call at the US embassy in Helsinki described it as a hoax and a “horrible coincidence”.

But for 36 years, Dr Swire and other UK relatives have called for a public inquiry to examine the warnings and the failures of airline and airport security which allowed the bomb to slip through. As the drama points out, this inquiry has never happened.

Just last week, Scotland’s First Minister John Swinney said he could not consider the request while the judicial process in the US was still going on.

PA Media

PA MediaThe destruction of Pan Am 103 was an attack on the United States. Of the 270 victims, 190 were American. The rest came from 20 other countries, including 43 people from the UK.

Suspicion initially fell on Iran.

Five months before Lockerbie, an American warship shot down an Iranian airliner over the Persian Gulf after mistaking it for a fighter jet. The 290 men, women and children on board were killed. Iran swore revenge.

In October that year, West German police raided flats in Frankfurt where members of the PFLP-GC were preparing bombs in radio cassette players. They had timetables for airlines, including Pan Am.

Less than two months later, Pan Am 103 was brought down.

A joint Scottish/US investigation established that the bomb had been concealed inside a different model of radio cassette player in a suitcase.

The involvement of the PFLP-GC and Iran made sense, but Scottish police and the FBI say they found no evidence to justify charges against anyone from the group or Iranian officials.

The defence at the Lockerbie trial blamed the Palestinians for the bombing but the judges said they had heard nothing to prove their involvement or undermine their belief that Libya was responsible.

Reuters

ReutersThe prosecution case was that the Libyans smuggled the unaccompanied suitcase onto an Air Malta flight to Frankfurt, where it was loaded on to Pan Am 103a, the feeder flight for Pan Am 103. This assertion was supported by baggage records.

The suitcase was transferred onto Pan Am 103 at Heathrow.

Clothes from the suitcase were traced to a shop on Malta. Its owner told the court they were bought by a Libyan who resembled Megrahi, a crucial piece of evidence which has been hotly disputed ever since.

The day before the bombing, Megrahi travelled to Malta using a false passport supplied by the Libyan intelligence service.

He was at Malta airport when luggage was being loaded onto the flight to Frankfurt and flew back to Libya shortly afterwards. He never used the passport again and later denied being on Malta.

Dr Swire and his supporters remain convinced the US needed to shift the blame from Iran, which was backing groups holding American hostages.

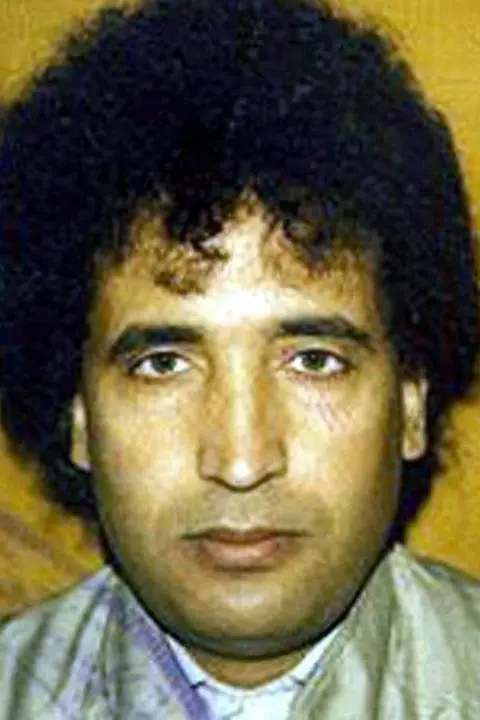

Crown Office

Crown OfficeMegrahi lost his first appeal against his conviction in 2002 but won a second after a four-year investigation by the independent Scottish Criminal Cases Review Commission.

The SCCRC found there was no proper basis in allegations that investigators had manipulated, altered or fabricated evidence to make a case against Megrahi.

But it did conclude the court had no reasonable basis for finding that Megrahi bought the clothes in Malta, undermining a cornerstone of the prosecution case.

The commission said the verdict had been “unreasonable” and that Megrahi might have suffered a miscarriage of justice.

The case was sent back to the courts but Megrahi abandoned the appeal after he was diagnosed with prostate cancer.

MAHMUD TURKIA/AFP via Getty Images

MAHMUD TURKIA/AFP via Getty ImagesTerminally ill, he was freed on compassionate grounds by the Scottish government in 2009 and died three years later in Tripoli.

In 2020, after a request from Megrahi’s family, the SCCRC referred the case back to the appeal court a second time.

Once again, the commission said the trial court should not have accepted that Megrahi bought the clothes that were beside the bomb.

It also said he was denied a fair trial because of non-disclosure; the prosecution didn’t give the defence certain information which could have helped him.

Five of Scotland’s most senior judges upheld the conviction, saying the identification of Megrahi was just one part of the overall picture and the information which was not disclosed to the defence would not have changed the verdict.

The bomb timer fragment

The single most important piece of evidence from the case was a thumbnail-sized fragment of circuit board, found embedded in the neck band of a shirt from the suitcase that held the bomb.

The trial judges accepted evidence from scientists that it was part of an MST-13 bomb timer sold to Libya by MEBO, a Swiss firm with connections to Megrahi.

Towards the end of the Sky drama, Dr Swire becomes even more convinced of Megrahi’s innocence after learning that tests on the fragment showed it had a different coating from the MST-13 timers obtained by Libya.

This evidence was examined by the SCCRC before it sent Megrahi’s conviction back to the appeal court in 2020.

It said it was “not persuaded” that it called into question the judges’ conclusion that the fragment came from an MST-13 timer which triggered the bomb.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe drama tells viewers that the British government used public interest immunity certificates to prevent the disclosure of “secret intelligence documents allegedly implicating Iran and the PLFP-GC” and that those documents “remain classified to this day”.

The certificates were imposed in 2008 and again in 2020, when the UK’s foreign secretary said their disclosure would harm the UK’s international relations and damage counter-terrorism liason and intelligence gathering.

An independent investigator from the SCCRC was allowed to view the two documents in 2006 and concluded that the prosecution’s failure to disclose one of them to the defence might have resulted in a miscarriage of justice.

The matter wasn’t dealt with in court because Megrahi abandoned his second appeal.

In 2019, the SCCRC looked at them again. This time it decided one of the documents involved inadmissable hearsay and the second would not have made any difference to the defence, had it known about it.

The appeal court accepted the SCCRC’s views and the government’s argument that disclosure could harm national security.

Carnival Film & Television

Carnival Film & TelevisionThe Sky drama informs its audience that some names, scenes and characters have been “changed or fictionalised for dramatic purposes”.

There are examples of that throughout, including its portrayal of the day of the verdicts at the Lockerbie trial.

Megrahi stood trial alongside another Libyan, Al Amin Khalifa Fhimah, at Camp Zeist – a specially convened Scottish court in the Netherlands.

The programme ramps up the tension as the judges announce they have found Fhimah not guilty and Megrahi guilty. This prompts jubilation among almost all of the relatives in the court’s public gallery, with people leaping to their feet and hugging each other.

A distressed young Libyan woman bangs on a glass partition shouting “That’s my dad!” as a bewildered Megrahi is sentenced to life in a Scottish prison.

Played by Colin Firth, Dr Swire faints and falls to the floor.

In real life, the judges announced the verdict the other way round. There were gasps and tears but no outbursts of emotion; the atmosphere remained sombre; Megrahi was impassive; no-one banged on the glass.

In a shocking and unforgettable moment, Dr Swire did faint and had to be carried from the courtroom. The sentence was announced later that day.

Carnival Film & Television

Carnival Film & TelevisionA group representing relatives of some of the American victims has criticised the Sky drama.

Victims of Pan Am Flight 103 said it “amplifies falsehoods and unsupported theories; ignores the work of hundreds of family members by focusing on one; disregards the work of investigators and prosecutors; and brings to life, in grotesque detail, the events of 21 December 1988”.

The group continued: “Worst of all, the series presents a convicted murderer as an innocent man that should be empathized with.”

Sky said it understood that there were “opposing opinions” and that the series did not attempt to tell the definitive version of the Lockerbie disaster or present a conclusion.

“We do not underestimate the responsibility of telling this story sensitively,” it added.

“We engaged with victims’ families and support groups throughout production and in the lead up to the series launch.”

Dr Swire said he hoped the series would cause people to “have another look at the criminal investigation after Lockerbie.

“I would like to know the whole truth about my daughter’s brutal murder along with those of 269 other people.”

The second Lockerbie trial

Scotland’s Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service said the trial had found that the bombing was orchestrated by the Libyan government and that multiple individuals were involved.

“Megrahi was found guilty and two appeals have upheld that conviction,” a spokesperson said.

“Scottish prosecutors are working with their US counterparts to support the current prosecution. The trial in Washington will bring the facts before the public again and the circumstances of what happened can be fully understood.”

In May, a Libyan man in his 70s will stand trial in Washington, accused of the destruction of a civil aircraft resulting in death.

Abu Agila Masud has denied building the bomb which destroyed Pan Am 103 in a Libyan intelligence operation involving Megrahi and Fhimah.

Prosecutors in Washington are likely to lead evidence from the first trial along with new information gathered in the years that followed.

The defence will be armed with all the counter arguments from Megrahi’s legal teams and the SCCRC’s doubts over the safety of his conviction.

In addition to the Sky series, a BBC/Netflix drama on Lockerbie is also due to be screened later this year, focusing on the joint Scottish/US investigation.

More than 35 years after the tragedy, the controversy surrounding the deadliest terror attack in British history shows no sign of fading away.

David Cowan and presenter Kaye Adams, who reported from Lockerbie on the night of the disaster, will discuss the story with Martin Geissler on BBC News Scotland’s new podcast, Scotcast. The episode will be available on BBC Sounds at 17:00 on Wednesday and broadcast on the BBC Scotland channel at 23:00.