Will electric planes and sustainable fuel make Heathrow’s third runway green?

Getty Images

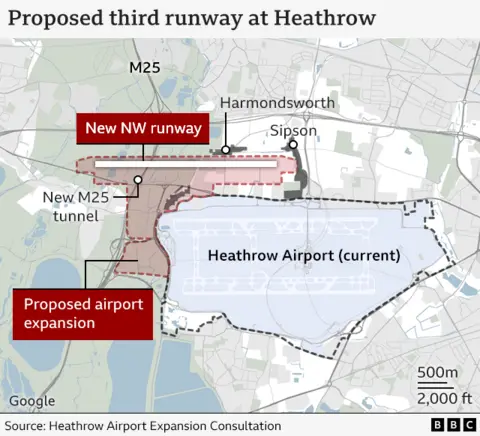

Getty ImagesThe government is set to give its backing to the construction of a third runway at London’s Heathrow Airport on Wednesday.

Chancellor Rachel Reeves is expected to announce the decision in a major speech on achieving economic growth.

The expansion of Heathrow has long been opposed by green groups and her announcement will be extremely controversial, not least because of its environmental impact.

Reeves claimed at the weekend that “a lot has changed in aviation” since plans for a new runway at Heathrow were first discussed decades ago.

She said “sustainable aviation fuel” would cut emissions, that there was huge investment going into electric planes, and that a third runway would mean fewer planes circling over London as pilots wait to land.

BBC Verify has assessed whether the Labour government’s reasoning really stacks up.

Is sustainable aviation fuel the answer?

By burning traditional jet fuel – kerosene – aircraft release carbon dioxide, a planet-warming gas.

“Sustainable” fuels are alternatives to fossil fuels, made from renewable sources. They can come from agricultural waste and from used cooking oil, which the government argues emits 70% less carbon emissions over the course of their lifetime. This is because the plants from which the fuels are often derived were absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere when they were growing.

The previous government announced that by 2030, 10% of all jet fuel used in flights taking off from the UK must be sustainable as a way to reduce the impact of aviation on emissions. This target has been kept by Labour.

But there are a number of issues with using the rollout of sustainable fuels as a justification for airport expansion.

Sustainable fuels are currently used in a tiny fraction of jet fuel – the government target for 2025 is 2% – and scaling this up will be a major challenge. They are not completely carbon-neutral because of the energy used in producing, refining and transporting them and can vary widely between fuel types.

Many environmentalists argue that expanding UK airports is incompatible with the UK’s net zero targets because there is currently no viable widespread alternative to fossil-fuel based aviation fuel for powering planes.

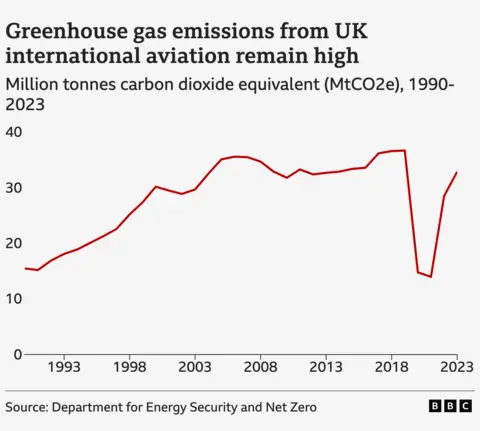

Provisional official figures show that greenhouse gas emissions from UK international aviation in 2023 were 32.9 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent. That was roughly 8% of the UK’s total greenhouse gas emissions (including international aviation) of 423.3 million tonnes in that year.

Aside from a major dip in the pandemic, there has been no substantial change in emissions from UK international air travel over the past 20 years.

In recent years, the growth of UK international aviation emissions has actually been lower than that of passengers, which has been attributed to more fuel-efficient engines – yet it’s unclear if this trend would continue with a third Heathrow runway.

And there are questions about the effectiveness of airlines’ schemes to “offset” emissions by decarbonising elsewhere, like planting trees.

Are electric planes viable?

There are already a number of small battery-powered electric planes and investment in the technology is increasing.

If planes are powered by electricity generated from renewables like wind and solar, flying could result in zero carbon emissions.

But the weight of batteries is currently regarded as a major obstacle to a large-scale expansion of electric-powered flights, particularly for long haul journeys.

Technological breakthroughs in battery weights are possible, but widespread electric air travel is not seen as a realistic prospect in the near future by most analysts.

Would a third runway reduce circling flights?

Heathrow Airport has reported that in 2023 an average of 232 aircraft, more than a third of all arriving planes, were held in one of four “stacks” above London each day, where they circle at or above 7,000 feet until there is space to land at the airport. They spent an average of 6.85 minutes in a stack.

Circling at low altitude is less fuel efficient than cruising at high altitude, because of extra air resistance.

As a result, since 2014 Heathrow and air traffic control company NATS have been working with their counterparts across Europe to slow inbound flights down from as far as 350 miles away, when delays over London begin to build.

But it is difficult to estimate whether an extra Heathrow runway would reduce stacking, let alone reduce emissions.

The BBC has asked NATS for updated figures on how circling times over Heathrow have been changing and the impact on emissions, and we asked the Treasury for further details about the chancellor’s claim about circling flights.

Expanding Heathrow: The pros and cons

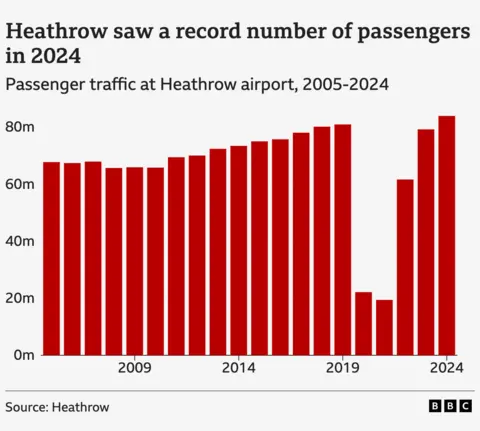

Advocates of expansion of the UK’s largest airport say it is vital for boosting national economic growth – not least because demand is outstripping supply.

Heathrow has reported that a record 83.9 million passengers travelled through its terminals in 2024. That was 4.7 million more than in 2023 and three million more than the previous annual peak in 2019, before the pandemic.

The airport has no free landing slots available, meaning that airlines have to buy slots from other airlines if they want to expand their services operating from the airport. In 2016, Oman Air paid a reported $75m (£60m) for a pair of early morning landing slots at Heathrow, for example. Such costs ultimately end up hitting passengers’ wallets through fares, according to research commissioned by Heathrow.

An independent report for the previous government, by Sir Howard Davies, concluded in 2015 that the south east of England needed a new runway and that the “best answer” was an expansion of Heathrow.

Yet by approving a third Heathrow runway, Reeves appears to be conflicting with the advice of the government’s own independent adviser on cutting emissions, the Climate Change Committee (CCC). It has repeatedly cautioned against airport expansion without a framework in place to manage overall national capacity.

In a report to Parliament last July, the committee said: “No airport expansions should proceed until a UK-wide capacity management framework is in place to annually assess and, if required, control sector GHG [greenhouse gas] emissions and non-CO2 effects.”

In response, the government said last December that it “recognises a role for airport expansion where it provides economic growth and is compatible with our legally binding net zero target and strict environmental standards. We are currently considering our wider approach to decarbonising aviation”.

Ministers could theoretically still stay within the government’s legislated carbon budgets if they increased the rate of emission reductions from other sectors of the economy while allowing aviation emissions to rise.

Yet achieving deeper reductions elsewhere will be difficult and cannot be guaranteed. Reeves and Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer are unlikely to be in power by the time any third Heathrow runway could be finished, many years ahead, frustrating mitigation plans and accountability for its impacts.

Additional reporting by Gerry Georgieva and Mark Poynting