Israel’s looming Unrwa ban a catastrophe, UN Palestinian refugee agency warns

Reuters

ReutersAs Israel prepares to outlaw the main UN agency for Palestinian refugees on Thursday, there are warnings that it could undermine vital aid delivery and long-term chances of peace.

Israeli officials have not spelt out how they will enforce the legislation passed last year by Israel’s parliament, which accused Unrwa of being complicit with Hamas – an allegation the agency denied.

“It will be a catastrophe if this ban takes place,” says Juliette Touma, communications director of the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (Unrwa).

“It will deepen and further the suffering of the Palestinian people who rely on the agency for their survival, for their education and healthcare.”

Even before 15 months of brutal war left the vast majority of the two million people in Gaza displaced and homeless, most were registered refugees.

Unrwa camps were first set up in Gaza to house Palestinians who fled or were expelled from their land in fighting before and after the state of Israel was created in 1948.

For seven decades, those original refugees and their descendants – as well as a new wave of refugees created by the 1967 Middle East War – have been cared for by Unrwa.

Across the Middle East – in Jordan, Syria and Lebanon as well as the occupied Palestinian territories – there are some six million Palestinian refugees.

They include the Naseer family, currently huddled in a tent in the courtyard of an Unrwa school-turned-shelter in Deir al-Balah in central Gaza. They are from Beit Hanoun in the north but have decided to delay returning to the rubble of their home, even as a fragile ceasefire has taken hold.

“I have a disability, and I have a big family,” says Ahmed Naseer, a father of nine who says he struggles to access food aid. “Right now, we get hot meals twice a week from Unrwa and people are still starving. What would it be like if it stops for good?”

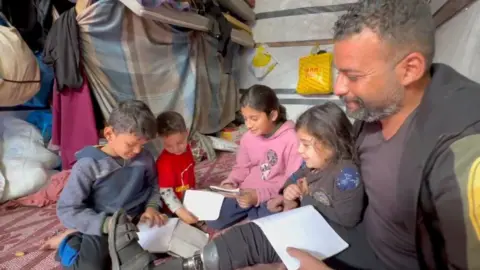

Ahmed says his children – all formerly Unrwa students – have forgotten basics like their times tables, as their schools have been closed for so long. Now they worry their lessons will never resume.

“We just want to go back to school to make up the days we’ve lost,” says 16-year-old Malak. “Every child in Gaza has a dream of what they want to do when they grow up – to be a doctor or engineer. If education is stopped, there will be no future for us.”

The full implications of legislation passed by the Israeli parliament are not yet clear. In October, it voted overwhelmingly to ban Unrwa activity on Israeli soil and forbid contact between Israeli officials and Unrwa employees. The laws come into effect on 30 January.

However, the legal wording does not directly address the agency’s operations in Gaza, or the occupied West Bank. UN workers say it will ultimately be impossible to function in either location without co-ordinating with Israel’s military authorities.

Talking to the BBC, Israeli Deputy Foreign Minister Sharren Haskel suggests that only Palestinian officials should deal with Unrwa in the West Bank.

She accuses the agency of being infiltrated by Hamas in Gaza and becoming a security threat.

“Israel actually gave more than a year to the international community to clean out this organisation, but it didn’t. It tried to sweep it under the rug and turn a blind eye to breaching the law of neutrality,” Haskell says. “This was the only logical step.”

Israel has long accused Unrwa of perpetuating conflict by keeping alive Palestinian hopes of returning to their historic homeland.

However, tensions have risen dramatically since the Hamas-led attacks on Israel on 7 October 2023 and the war they triggered.

A year ago, Israel accused 18 Unrwa employees of taking part in the deadly assault. A UN investigation then found that nine employees may have been involved and the agency fired them. UN officials reject most of Israel’s accusations against it and insist Unrwa is impartial.

Many international donors, including the UK and the European Union, have since resumed donations to the agency.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThere is nervousness among tens of thousands of Palestinian refugees in occupied East Jerusalem, where Unrwa workers could be seen stacking boxes outside some offices this week.

Israel’s government has ordered Unrwa to vacate its compound in this part of the city, which it has annexed in a move not recognised internationally.

“You can see in front of us the Unrwa Shufat health centre where I was director, and on the other side are the girls’ school and separate boys’ one,” says Salim Anati, retired GP, as he shows me along the bustling main road of Shufat refugee camp where he grew up.

He tells me how his parents – who were expelled from their homes in what is now Lod in Israel – never believed that the refugee camp or Unrwa would become permanent fixtures.

The fate of refugees – a core issue in the Israel-Palestinian conflict – was meant to be worked out in peace talks. However, they stalled a decade ago. Now Palestinians feel Israel is using the opportunity to push its own political solution.

Dr Anati says Palestinians refuse to accept the abolition of Unrwa and its services.

“All people are shocked, because it’s something fundamental for us as refugees and Unrwa represents the international agreements and our dream of the right of return to our villages and cities.”

The UN has repeatedly said there is no alternative to Unrwa.

At a heated meeting in New York on Tuesday, senior UN officials and every member of the Security Council except the US – Israel’s closest ally – described Israel’s actions as a violation of international law and its obligations under the UN charter.

The deputy US ambassador to the UN, Dorothy Shea, accused the Unrwa head, Philippe Lazzarini, of being “irresponsible and dangerous” when he outlined the expected “disastrous” impact, particularly on aid in Gaza.

But Mr Lazzarini said the legislation would impose “massive constraints”, particularly on the Gaza aid operation, and called on international powers to push back against it “in support of peace and stability”.