Rwanda and South Africa race to bring F1 back to Africa

Rwanda’s President Paul Kagame has endorsed the country’s bid for a Formula 1 race, but South Africa also hope to bring reigning champion Max Verstappen and the rest of the grid back to the continent

-

Published

It has been over 30 years since the roar of Formula 1 engines echoed on African soil but a heated race is under way to bring the sport back to the continent.

Rwanda and South Africa are vying for pole position and hope to realise their ambition in 2027.

Seven-time world champion Lewis Hamilton has long been an advocate for an African grand prix, and that sentiment is spreading among fellow drivers.

“I would like to race in Africa. We’re very excited to be on that road,” reigning champion Max Verstappen told BBC Sport Africa.

McLaren’s Lando Norris, meanwhile, thinks Africa would be “the perfect place” to introduce F1 to new audiences.

Rwanda is offering an innovative vision, aiming to blend motorsport with sustainability and natural beauty.

President Paul Kagame formally announced Rwanda’s bid in December and the country has the backing of the head of motorsport’s world governing body (FIA).

The FIA regulates F1, while Liberty Media are the holders of the competition’s commercial rights.

“Africa deserves a F1 event and Rwanda is the best place,” FIA president Mohammed Ben Sulayem told BBC Sport Africa.

Yet the South African bid has a rich history to draw on – as well as a track which is already built.

-

-

Published30 May 2024

-

-

-

Published21 January

-

Rwanda’s race through the hills

Rwanda’s F1 circuit is expected to be built in countryside close to where the new Bugesera International Airport is currently under construction, which is south of Kigali

Rwanda, often called ‘the land of a thousand hills’, plans to embrace its unique terrain.

A track, designed by former Benetton driver Alexander Wurz, is set to be constructed approximately 25km from the capital Kigali and promises to deliver a fast, flowing layout that winds through forests and around a picturesque lake.

It includes dramatic elevation changes and sharp corners which were described by Verstappen as “amazing” when the Red Bull Racing man visited Rwanda for the FIA Awards last month, while Ferrari driver Charles Leclerc is excited by the potential for overtaking opportunities.

But building a F1 circuit is no small feat, given it must meet stringent FIA safety standards and accommodate associated infrastructure including paddocks and media facilities.

Rwanda’s bid is part of a larger strategy to position the country as a global sports hub.

“It’s about Rwanda’s growth, people and place on the world stage,” said Christian Gakwaya, president of the Rwanda Automobile Club, the organisation in charge of motorsport activities in the country.

Some estimates suggest the project could cost Rwanda over $270m (£218m), yet the investment would help boost a tourism sector which generated over $620m (£501m) in 2023, according to the Rwanda Development Board.

“From job creation to infrastructure upgrades, these events touch lives across the country,” Rwanda’s chief tourism officer Irene Murerwa explained.

“The benefits trickle down to every Rwandan. Hosting F1 would be another step in our journey to becoming a world-class destination.”

A commitment to sustainability is another cornerstone of the bid, with Gakwaya pledging to “uphold the highest environmental standards”.

The country’s ban on single-use plastics and focus on harnessing renewable energy aligns with F1’s ambition to reach net-zero emissions by 2030.

‘Sportswashing’ allegations

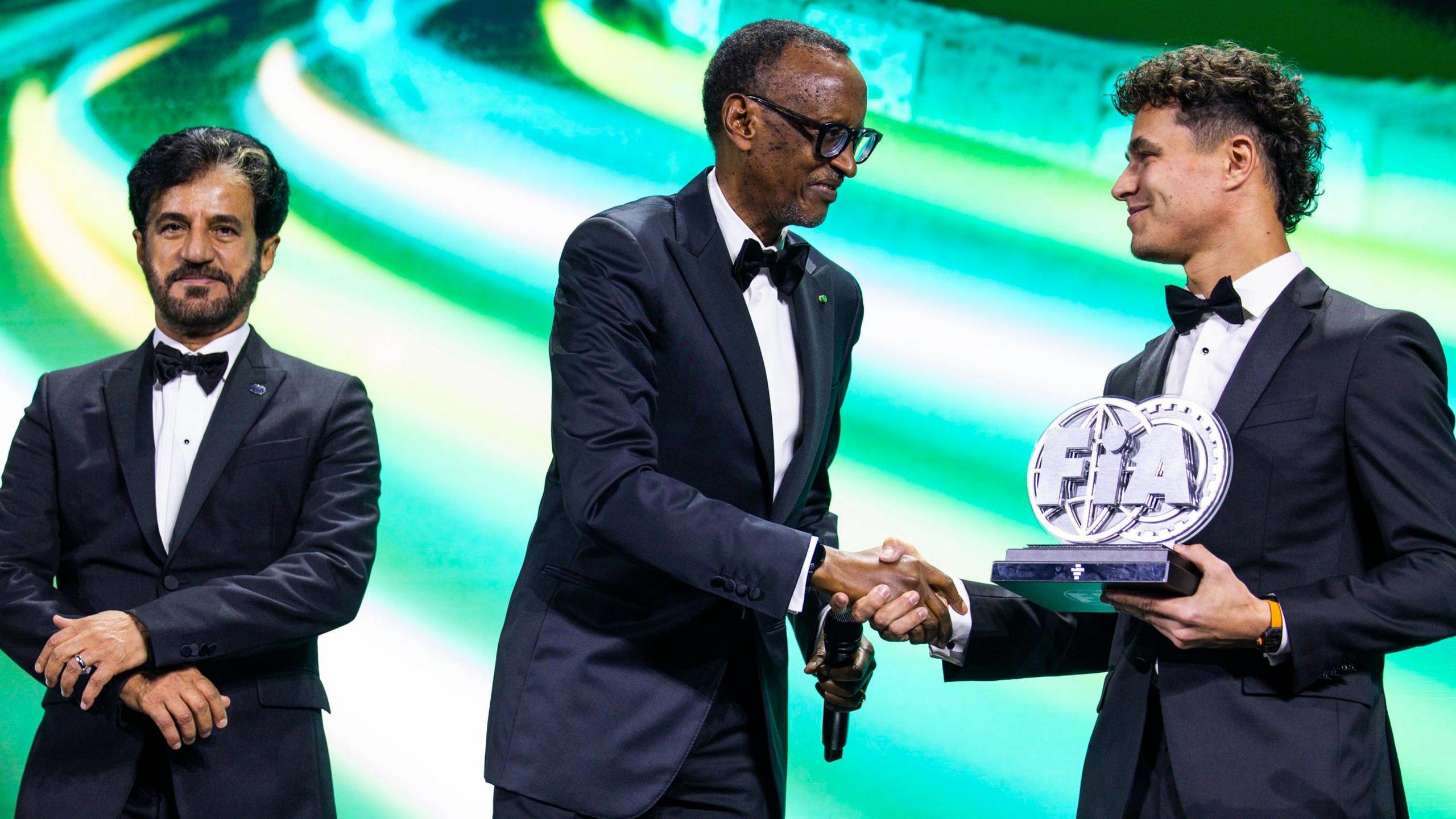

President Kagame was on stage alongside FIA president Mohammed Ben Sulayem (left) at the organisation’s awards in Rwanda last month, and handed one trophy to McLaren driver Lando Norris

Rwanda has already invested in sport, staging events like the Basketball Africa League, while the Visit Rwanda campaign, via partnerships with football clubs Arsenal, Paris Saint-Germain and Bayern Munich, has successfully raised the country’s profile.

In September it will become the first African nation to host cycling’s Road World Championships.

However, Rwanda’s government has been accused of investing in sport to enhance its global image and mask what one organisation describes as “an abysmal track record” on human rights – a strategy labelled by critics as ‘sportswashing’.

“Rwanda has major flaws with due process which violate its own internal laws or international standards,” said Lewis Mudge, the Central Africa director at Human Rights Watch, a campaign group which investigates and reports on cases of abuse around the globe.

“Increasingly we’re seeing the space for freedom of expression, for some degree of political autonomy, is actually shrinking.”

The Rwandan government has dismissed these accusations, with chief tourism officer Murerwa calling them “a distraction” from the “amazing and outstanding achievements the country has made”.

Meanwhile, United Nations experts have accused Rwanda of worsening the humanitarian disaster in neighbouring DR Congo by supporting the M23 rebel group.

It is an assertion Rwanda has previously denied, despite UN experts presenting evidence in several reports.

At the weekend, the UN chief Antonio Guterres called on Rwanda to cease support for the M23 and to withdraw its own troops from Congolese territory.

Mudge claims that, should it award Rwanda a race, F1 would be ignoring its own due diligence process regarding human rights in host nations.

Asked about the accusations levelled against Rwanda, FIA president Ben Sulayem replied: “When people cannot get what they want they always blame it on sportswashing.

“I honestly don’t care about what they say. I believe that what we are doing is right. We have a general assembly. They approve everything.”

The home of African motorsport

The last F1 race on African soil was in 1993, when Williams-Renault driver Alain Prost won at the Kyalami track in South Africa

South Africa’s bid leans on its historic Kyalami circuit which hosted 23 F1 races between 1967 and 1993, and requires far fewer upgrades than building a brand new facility.

A committee has been formed to oversee a bid, with plans to appoint a promoter to collaborate with the government for cabinet approval.

Sports minister Gayton McKenzie is already keen, highlighting the “massive” economic impact of staging a F1 race that could bring hundreds of thousands of tourists.

McKenzie estimated the annual hosting cost at 2bn rand ($106m, £86m), yet reassured the public that private sector sponsors are showing significant interest – with offers exceeding $20m (£16.2m) for hospitality rights alone.

The minister dismissed concerns about F1 being a “rich man’s sport”, comparing it to South Africa’s hosting of the Fifa World Cup in 2010.

“People said hosting the World Cup would be a waste, but those same people attended the games,” he told BBC Sport Africa.

“F1 will have the same effect – it will create jobs, boost tourism, and showcase South Africa to the world.

“When people say money could be spent elsewhere, they miss the bigger picture.”

-

-

Published17 June 2022

-

-

-

Published31 December 2022

-

Reaching the chequered flag

Despite their differing approaches, both nations face significant challenges.

Even after securing a place in the calendar, the successful country must pay an annual race promotion fee of between $15m (£12.1m) and $50m (£40.5m) to Liberty Media, while yearly track maintenance fees would average $18m (£14.6m).

Beyond that, ensuring sufficient accommodation and transportation options for fans further adds to the immense investment required.

Whether Rwanda’s scenic hills or the Kyalami circuit are chosen, F1 is moving closer to a return to Africa.

When it does arrive, a spectacle combining history, innovation and opportunity will deliver a defining moment for the continent.

Related topics

-

-

Published27 February 2020

-