‘We’re trying to invoke emotion’: Stadium architects on what CGI tells fans

Reuters

ReutersIn the world of billionaires and the similarly wealthy teams they own, designing a state-of-the-art stadium goes beyond the visual.

In the offices of architecture firm Arup, there is a downstairs soundproof room with premium grade surround-sound speakers and a large screen. It looks like a small theatre.

“We can put a client in there and say, ‘when your team scores, this is what it will sound like if your stadium roof is shaped this way,'” says Chris Dite, who is responsible for the firm’s sports projects.

“But, if we change the roof shape to this, then this is what it will sound like.”

The way the pitch and intensity of the crowd noise changes in the aftermath of a goal is based on data from stadium projects the firm have completed over the last 25 years.

Dite’s previous work includes the Allianz Arena used by German football giants Bayern Munich and the Gtech Community Stadium where Brentford play.

Brentford FC/Getty

Brentford FC/Getty“If you can sit the client in those front rows and make them feel like they’re in it, that’s where you start to really invoke an emotional response,” Dite tells BBC News.

What a goal might sound like in the new Manchester United stadium was not part of the presentation given by the club earlier this week, but the design of the new £2bn ground certainly invoked emotional responses.

Some questioned how realistic it was to build such tall pillars from which a glass panelled canvas drapes over the new stands and surrounding grounds.

The three pillars in the artist’s impression, unveiled by the firm Foster and Partners, are a nod to the trident on the Red Devil’s crest.

“Gravity still exists, unfortunately for us,” remarks Dite. He says he “can’t comment on other architectural businesses” but that Arup doesn’t issue any public designs that haven’t been approved by structural engineers.

“We don’t want to get into the situation of showing a client or fans an image that everyone falls in love with, that everybody gets behind.

“And then, when it comes to being a finished building, everyone’s like ‘well, that doesn’t look anything like the picture’.”

Prof Kevin Singh, head of the Manchester School of Architecture, explains modern building techniques mean many of an architect’s ideas are possible to construct, though there are limitations.

Housing and infrastructure that surround an existing stadium, particularly in an inner city or residential area, can limit the scope of ambitious redevelopment.

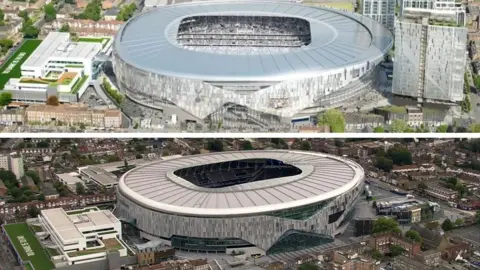

Tottenham Hotspur FC/BBC

Tottenham Hotspur FC/BBCBoth Liverpool and Newcastle United have had difficulties expanding their grounds due to their close proximity to houses.

One stand at Luton Town can only be accessed through an entrance sandwiched between a long row of terraced housing. Fans pass through a tight corridor before climbing staircases overlooking gardens of neighbouring properties.

Singh points towards the way Fulham have redeveloped Craven Cottage in a residential part of west London and Everton’s new ground at Bramley-Moore Dock as good examples of stadiums that “fit into its place”.

He said: “Everton’s feels contextual. You know it’s on the dock and it has some nods to Goodison Park,” he told the BBC. “When you saw the images of the stadium, it looked like the sort of thing you would build there.”

In contrast, he thinks Man Utd have chosen to construct something striking that can’t be confused for any other stadium.

“It’s very much an iconic thing in itself,” he says. “They’re justifying that sort of design because of the trident.”

Singh adds: “I think nobody could say that the proposal for Old Trafford is like anything else. I think avoiding anonymity was probably a key consideration.”

Everton FC/PA

Everton FC/PADite agrees, saying how much a stadium stands out in its local area is often something that has to be discussed with planners.

“Some buildings make the statement that ‘I want to be seen’ … I think Tottenham’s stadium does that and certainly the images we’ve seen this week from Manchester show it’s a statement – an iconic piece of architecture.”

He adds: “A lot of that is around the client’s appetite to make a statement.”

For Singh this goes hand in hand with a club’s wider ambitions around branding and what message it is trying to convey about itself.

“We’re in a world now where brand is so important … Anybody can support a team from anywhere – you can watch every single game on TV,” he says.

“It’s a global marketplace now and so clubs are competing, you know, all over the world for fans and their attention. So they have an identity in mind and, of course, their stadium is a huge part of that.”

Club greats and the local mayor hail the project as giving the club the world-leading stadium it deserves.

Some fans are stunned by this exciting look into the future while others feel it looks like a generic entertainment venue devoid of local connection.

Fans of rival clubs have commented it looks like a circus tent, a fitting reflection of the woes suffered by the Premier League’s most valuable team – they are 15th in the table.

For Dite, as much as modern stadium design now includes acoustic considerations and brand messaging, the core tenets have long been the same.

“It is not wildly different from when the Colosseum was built 2,000 years ago”, he says. “That spectators are really participants who want to be part of something bigger than themselves.

“You know what it’s like, when it’s the last five minutes of a close game, everyone gets behind the team.

“It becomes a collective experience. You’re not watching the action, you’re in it.”