Why voters fall out of love with liberation movements

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAfrica’s oldest liberation movement is in trouble and may be going the way of similar groups across the continent.

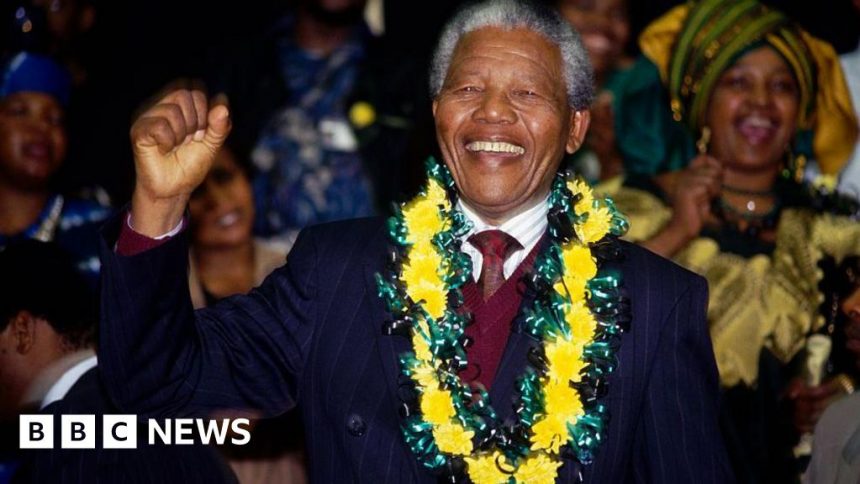

The African National Congress (ANC) – founded in South Africa more than a century ago – has lost its majority in parliament for the first time in 30 years, although it remains by far the country’s most popular party.

No longer, it seems, were large numbers of voters reflexively willing to give the party of Nelson Mandela their support because it had lead the struggle against the racist apartheid system.

This mirrors the decline of other parties that battled colonial rule and made it to power, which have subsequently fallen prey to corruption, cronyism and a disgruntled population hungry for change.

Some of those liberation movements which remain in power in southern Africa are accused of only doing so by stealing elections.

“It is inevitable that people will start to want change,” said researcher David Soler Crespo, who has written about the “slow death of liberation movements”.

“It’s impossible for the same party to be democratically elected for 100 years.”

However, they have managed to impose a strong grip, not only on the apparatus of power, but also on the psyche of the nation.

As the successful movements transitioned from the bush to the office, they touted themselves as the only ones that could lead.

They ingrained the movement into the DNA of the country, making it difficult to separate the party from the state.

In Namibia, the phrase “Swapo is the nation, and the nation is Swapo” used during its struggle against apartheid South African rule, remains potent.

AFP

AFPLooking across the region, civil servants and government appointees, especially in the security forces and state-controlled media were often former guerrilla fighters, who may have put loyalty to the party before the nation.

“There is no line between state and party. It’s more than a party, it’s a system,” said Mr Crespo.

And the legacy of liberation is deeply embedded in the region’s culture, with stories of struggle shared across family dinner tables and national media continually reminding citizens of their hard-won freedom.

Liberation songs and war cries are sung in high schools, even at sports matches.

For citizens to move away from the liberation party is a big psychological wrench. But over time it does happen.

“People are no longer influenced by history when they vote,” Namibian social scientist Ndumba Kamwanyah told the BBC, reflecting on the declining support for Swapo, which has been in power since 1990.

Many of the parties espoused socialist ideologies, but these have often fallen by the wayside over time and people have questioned whether citizens are benefitting equally.

One of the first independence movements in southern Africa to feel this disdain for history was Zambia’s United National Independence Party (Unip), which came into power in 1964 as British rule ended.

Throughout most of the 1970s and 1980s it governed the country as the sole legal party, with founding father Kenneth Kaunda at the helm. But discontent grew and in 1990 there were deadly protests in the capital, Lusaka, and a coup attempt.

The following year, the first multi-party elections for more than two decades saw President Kaunda lose out to Frederick Chiluba. Unip, once all-powerful, has now all but disappeared.

Liberation movements in Angola, Mozambique, Namibia and Zimbabwe remain in power but have all experienced a decline in support and vote share in general elections.

AFP

AFPIn Namibia, 2019 marked a watershed for Swapo as it lost its two-thirds parliamentary majority.

In the presidential election, Hage Geingob also suffered a sobering decline in popularity as his share of the vote dropped from 87% in 2014 to 56%.

The following year, Swapo suffered historic losses in regional and local elections.

Prof Kamwanyah, who campaigned for the party more than 30 years ago, says he maintains a deep respect for what the liberation government achieved in the past, but he is disappointed with the present reality.

“What the party is doing doesn’t reflect the core original values of why people died for this country,” the Namibian academic said.

Namibia will hold its general election in November and there is some speculation that it could suffer the same fate as the ANC.

“I think Swapo will win, but they will not get a majority,” Prof Kamwanyah said.

Ndiilokelwa Nthengwe, a 26-year-old Namibian activist, says there has been a generational shift.

“Our generation’s values don’t align with the government,” she told the BBC.

Ms Nthengwe has been at the forefront of many social movements in the country.

Young people value sexual and gender equality, she says, along with jobs and better healthcare.

“All the youth want is change, change, and more change.”

AFP

AFPBut whereas Namibia, along with South Africa, are seen as relatively open democracies, the governing parties in Zimbabwe, Angola and Mozambique have been accused of shutting down dissent in order to maintain their hold on power.

Election rigging, suppressing opposition parties and voter intimidation have been among their alleged tactics.

Adriano Nuvunga, chairperson of the Southern Defenders Observer Mission, has witnessed elections in Mozambique for the last two decades.

“All of the elections I’ve observed since 1999 were fraudulent,” said Mr Nuvunga.

He says he also saw voter intimidation and ballot tampering.

In Zimbabwe in 2008 Amnesty International documented unlawful killings, torture and other ill-treatment of opposition supporters between the first round and second round of the presidential vote. In fact most of Zimbabwe’s elections have been marred by allegations of tampering or intimidation of the opposition, although this is always denied by the ruling party, Zanu-PF.

Following the 2022 elections in Angola, thousands of people took to the streets to protest against alleged electoral fraud.

The longer the liberation movements have stayed in power, the more they are accused of corruption and cronyism and not governing in the interests of the people.

Chris Hani, the late South African anti-apartheid hero, foresaw this when he said: “What I fear is that the liberators emerge as elitists who drive around in Mercedes Benzes and use the resources of this country to live in palaces and gather riches.”

But one former Zimbabwean liberation fighter, who asked to remain anonymous, told the BBC that many of the movements had not had enough time to come to grips with the world order.

He pointed out that Europe endured authoritarian monarchies ruling for centuries and they have had time to learn and adapt.

“Liberation governments are still playing catch-up in a world that wasn’t designed for them,” he said.

Overthrowing colonial and white-minority rule was hard, but governing has brought other challenges.

Leading a revolutionary movement requires a single-mindedness and strict loyalty, while running a country needs greater flexibility, collaboration and the ability to balance the interests of different sections of the population.

Some movements have fallen short on this. And they may not have much time left.

But Mr Crespo maintains that if these parties reclaim the ideals that brought them into government, listen to the youth and find themselves again, they may be able to hold on a little longer.

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBCGo to BBCAfrica.com for more news from the African continent.

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, on Facebook at BBC Africa or on Instagram at bbcafrica