Will India’s Booker Prize-winning author face jail for 14-year-old remark?

AFP

AFPWill one of India’s most celebrated writers really face prosecution for things she said more than a decade ago?

Last week, 14 years after the original complaint, Delhi’s most senior official granted permission for the Booker Prize-winning author Arundhati Roy to be prosecuted under India’s stringent anti-terror laws. The Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) is notorious for making it exceptionally challenging to get bail, often resulting in years of detention until the completion of trial.

The Modi government has been accused of using the law to silence critics, including activists, journalists and civil society members.

Ms Roy, 62, an outspoken writer and activist, is in the dock for comments on Kashmir, a perennial lightning rod in India.

“Kashmir has never been an integral part of India. It is a historical fact. Even the Indian government has accepted this,” she said at a stormy, day-long conference in Delhi, organised by the Committee for the Release of Political Prisoners, in October 2010.

At the time, Indian-administered Kashmir was in turmoil, with locals describing it as a fierce uprising against India.

Ms Roy’s remarks had followed the deaths of dozens of protesters since fresh pro-freedom demonstrations broke out earlier that year.

India and neighbouring Pakistan, nuclear armed-rivals, claim the disputed region in full and have fought two wars over it.

Ms Roy’s remarks predictably set off a firestorm of protest, with many critics questioning her loyalty to India, and the federal government, then led by the Congress party, threatening to arrest her on charges of sedition. A senior minister said while India enjoyed freedom of speech, “it can’t violate the patriotic sentiments of the people”.

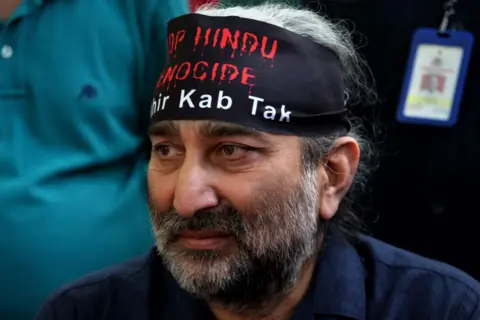

There were protests outside Ms Roy’s home in an upscale Delhi neighbourhood. A criminal complaint was lodged against her and another defendant Sheikh Showkat Hussain, a law teacher from Kashmir, accusing them and two others of sedition.

AFP

AFPMs Roy defended her right to free speech soon after the controversy. “In the papers some have accused me of giving ‘hate-speeches’, of wanting India to break up. On the contrary, what I say comes from love and pride,” she wrote in a response.

“It comes from not wanting people to be killed, raped, imprisoned or have their finger-nails pulled out in order to force them to say they are Indians… Pity the nation that has to silence its writers for speaking their minds.”

Lawyers are puzzled by the decision to prosecute Ms Roy more than a decade after her speech. She was originally accused of sedition, but the Supreme Court suspended the colonial-era sedition law in May 2022; invoking UAPA charges allows the state to bypass the statute of limitations and proceed with the case.

Ms Roy has been a trenchant critic of Mr Modi’s government, which rights groups accuse of targeting activists and muzzling free speech. The permission for her prosecution comes just after Mr Modi’s re-election for a third term.

Many view this as a political signal that the BJP will continue its strong-arm tactics, even in coalition government. Sushil Pandit, the main complainant from 2010, refused to speculate on the delay. “Those who sat on these files and decided to act now should explain. There must be an inquiry into why this was delayed, and accountability should follow,” he told Times Now television.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMany view this as another attempt to silence Mr Modi’s critics. Writer Amitav Ghosh wrote on X: “The hounding of Arundhati Roy is absolutely unconscionable. She is a great writer and has the right to her opinion. There should be an international outcry against prosecuting her for something she said a decade ago.”

When Delhi authorities approved the case to proceed in court in October, Canadian writer and activist Naomi Klein warned Mr Modi on X: “You have no idea what you will unleash by pursuing this political prosecution to silence your most eloquent critic.”

What exactly transpired on the day when Ms Roy made the comments?

In the minutes of the conference, Shivam Vij described it as “historic in every aspect given the topicality of the issue”. Speakers included a well-known poet, several activists and journalists.

Ms Roy anticipated a heated debate. “She began her speech by asking those who wanted to throw shoes to her to do so now,” Mr Vij wrote.

Shuddhabrata Sengupta, an artist, writer and curator who spoke at the event, wrote that the only “provocative actions” – interruptions, heckling, attempts to throw objects at stage – came from “self-declared Indian patriots”. They were allowed to speak but were asked not to disrupt the proceedings, he noted.

However, Mr Pandit, the Kashmiri activist present at the meeting, had a different view.

“Openly, in the heart of the capital, Delhi, a call for the destruction of the Indian Union as a colonial, occupying state, a state that has subjugated people… had no business to survive. Such statements were made. A call to arms rang out from the podium repeatedly… by Arundhati Roy [among others].”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOver the past two decades, Ms Roy has written several non-fiction books and numerous essays on topics like nuclear weapons, Kashmir, big dams, globalisation, Dalit icon BR Ambedkar, meetings with Maoist rebels, and conversations with Edward Snowden and John Cusack.

The God of Small Things, a riveting family saga inspired by her family childhood, picked up the 1997 Man Booker Prize – a “Tiger Woodesian debut” gushed John Updike – and made Roy a celebrity writer at 35.

The 62-year-old author is also a polarising figure in India.

Admirers see her as a leading voice for liberal values and a champion of the marginalised.

Critics, however, have burned her effigies, disrupted her events, and she has faced charges of sedition and contempt, even spending a day in jail for protesting against big dams.

They find a lot of her non-fiction writings shrill, naïve, adolescent, self-indulgent and simplistic, peddling “picturesque poverty”. One critic wrote that so often in her essays Ms Roy “never really gets to grips with the evidence”.

Since Ms Roy’s 2010 remarks, significant changes have occurred.

In 2019, Mr Modi’s government revoked Kashmir’s semi-autonomous status, dividing the region and reducing its political autonomy under direct federal control.

Many believe freedom of expression has also declined: since 2014, India has fallen from 150th to 161st in media freedom rankings by Reporters Without Borders, out of 180 countries.

Ms Roy has declined to comment on the latest development.

It is unclear if the police have investigated the allegations or have evidence against her and the other accused.

Two individuals named in the original complaint have passed away. But one thing is certain. If one of India’s most celebrated writers faces imprisonment under a draconian anti-terror law, it will ignite global condemnation and outrage.