China is the true power in Putin and Kim’s budding friendship

Reuters

ReutersThe welcome hug on the tarmac at 03:00, the honour guard of mounted soldiers, the huge portraits of Kim Jong Un and Vladimir Putin hanging side by side in the centre of Pyongyang – all of this was designed to worry the West.

Mr Putin’s first visit to Pyongyang since 2000 was a chance for Russia and North Korea to flaunt their friendship. And flaunt it they did, with Mr Kim declaring his “full support” for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Seoul, Tokyo, Washington and Brussels will see great peril in those words and in the stage-managed meeting. But the fact is the two leaders feel they need each other – Mr Putin badly requires ammunition to keep the war going and North Korea needs money.

However, the real power in the region was not in Pyongyang – and nor did it want to be. Mr Putin and Mr Kim were bonding on China’s doorstep and so would have been wary of provoking Beijing, a vital source of both trade and clout for these two sanctioned regimes.

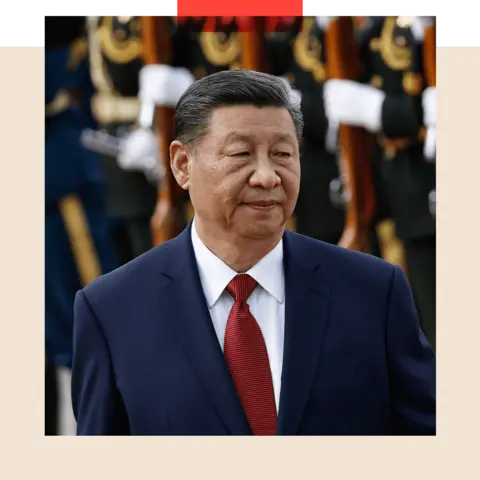

And even as Mr Putin hails his “firm friendship” with Mr Kim, he must know it has a limit. And that limit is Chinese President Xi Jinping.

A wary Beijing is watching

There are some signs Mr Xi disapproves of the burgeoning alliance between two of his allies.

Reports suggest Beijing urged President Putin not to visit Pyongyang straight after meeting President Xi in May. It seems Chinese officials did not like the optics of North Korea being included in that visit.

Mr Xi is already under considerable pressure from the US and Europe to cut support for Moscow and to stop selling it components that are fuelling its war in Ukraine.

And he cannot ignore these warnings. Just as the world needs the Chinese market, Beijing also needs foreign tourists and investment to fight off sluggish growth and retain its spot as the world’s second-largest economy.

It is now offering visa-free travel to visitors from parts of Europe as well as from Thailand and Australia. And its pandas are once again being dispatched to foreign zoos.

Perceptions matter to China’s ambitious leader, who wants to take on a bigger global role and challenge the US. He certainly does not want to become a pariah or face fresh pressure from the West. At the same time, he is still managing his relationship with Moscow.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhile he has not condemned the invasion of Ukraine, he has so far failed to provide significant military assistance to Russia. And during the meeting in May, his cautious rhetoric was in contrast to Mr Putin’s florid compliments about Mr Xi.

So far, China has also provided political cover for Mr Kim’s efforts to advance his nuclear arsenal, repeatedly blocking US-led sanctions at the United Nations.

But Mr Xi is no fan of an emboldened Kim Jong Un.

Pyongyang’s weapons tests have enabled Japan and South Korea to set aside their bitter history to ink a defence deal with the US. And when tensions rise, more US warships turn up in Pacific waters, triggering Mr Xi’s fears of an “East Asian Nato”.

Beijing’s disapproval may force Russia to reconsider selling more technology to the North Koreans. The possibility of that happening is also one of the US’ biggest concerns.

Andrei Lankov, the director of NK News, says he is sceptical: “I don’t expect Russia to provide North Korea with a large amount of military technology.”

He believes Russia “is not getting much and probably creating potential problems for the future” if it did so.

While North Korean artillery would be a shot in the arm for Mr Putin’s war effort, swapping missile tech for it would not exactly be a great deal.

And Mr Putin might realise it’s not worth irking China, which buys Russian oil and gas, and remains a crucial ally in a world that has isolated him.

Pyongyang needs China even more. It’s the only other country Mr Kim visits. Anywhere between a quarter to a half of North Korea’s oil comes from Russia, but at least 80% of its business is with China. One analyst described the China-North Korea relationship as an oil lamp that keeps burning.

In short: however much Mr Putin and Mr Kim try to appear as allies, their relationship with China is far more important than what they share.

China is too important to lose

Despite their avowed fight against the “imperialist West”, this is a wartime partnership. It may develop but, for now, it appears transactional, even as they upgrade their partnership to the level of “alliance”.

The impressive-sounding Comprehensive Strategic Partnership agreement between the two countries, announced at the meeting between Mr Putin and Mr Kim, is no guarantee that Pyongyang can keep supplying ammunition.

Mr Kim needs supplies for himself as he has a front of his own to maintain – the Demilitarised Zone (DMZ) border with South Korea.

Analysts also believe Russia and North Korea use different operating systems, with the latter’s being low-quality and growing old.

More importantly, Russia and North Korea did not prioritise their relationship for decades. When he was friendly with the West, Mr Putin sanctioned Pyongyang twice and even joined the US, China, South Korea and Japan to persuade the North to give up its nuclear programme.

When Kim Jong Un ventured out for a whirlwind of diplomatic summits in 2019, he met Vladimir Putin only once. Back then Mr Kim’s wide smiles, hugs and handshakes were for the South Korean president Moon Jae-in. They met three times.

He exchanged “love letters” with then US President Donald Trump before their three meetings – a man he once called a “dotard” suddenly became “special”. He also held three summits with Mr Xi, the first international leader he ever met.

So Mr Putin is new to the party. And yet he has not turned on the charm, while Mr Kim has lined the streets with roses and red carpets.

The Russian leader’s column in the North Korean state newspaper highlighted shared interests to “resolutely oppose” Western ambitions to “hinder the establishment of a multi-polar world order based on a mutual respect for justice”.

But it was missing the flattery he heaped on Mr Xi, who he declared was as close as a “brother”, while praising a slowing Chinese economy for “developing in leaps and bounds”. He even said his family were learning Mandarin.

He certainly would not dare keep President Xi waiting for hours and arrive as late as he did in Pyongyang. They also don’t seem to have worked out who is the more important partner, judging by the awkward moment where they debated who should get in a car first.

With China, they are both supplicants. And without China, they and their regimes will struggle.

BBC InDepth is the new home on the website and app for the best analysis and expertise from our top journalists. Under a distinctive new brand, we’ll bring you fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions, and deep reporting on the biggest issues to help you make sense of a complex world. And we’ll be showcasing thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. We’re starting small but thinking big, and we want to know what you think – you can send us your feedback by clicking on the button below.