What impact could this election have on Scottish independence?

Getty Images

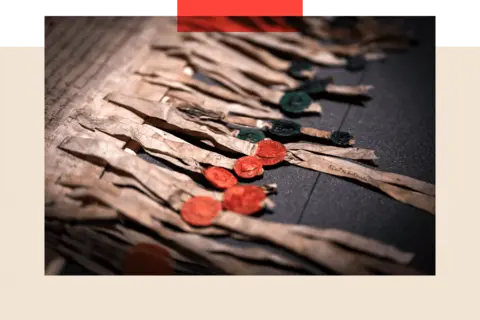

Getty ImagesWhen Scotland declared its independence from England, the words came from the heart.

“It is in truth not for glory, nor riches, nor honours that we are fighting, but for freedom alone, which no honest man gives up but with life itself.”

Seven centuries have passed since the Declaration of Arbroath, and Scottish nationalism now strikes a rather different tone.

“We are a moderate left-of-centre party in the mainstream of Scottish public opinion,” said the Scottish National Party (SNP) leader, John Swinney, as he unveiled his party’s manifesto for the general election.

Independence, he said, can deliver “a stronger economy and happier, healthier lives”.

Braveheart it was not. Nowadays, independence is presented not as a cry for freedom, but as a practical solution to financial hardship and inequality.

That strategy has worked well for the SNP in power during a prolonged period of Conservative government at Westminster.

But now, polls suggest, the nationalists’ decade-long dominance of Scottish politics is under threat from a resurgent Labour Party which hopes to gain at least a couple of dozen seats from the SNP while trying to form the next UK government.

In the key battleground of Glasgow, where the SNP will be defending six seats on 4 July, Ashleigh Morrison is at lunch with a friend in an Italian café on the city’s cosmopolitan south side.

Like many voters, she is worried about high prices, the state of public services, and the idea that, in her view, the SNP “are in a bit of a mess”.

“I’m a wee bit exhausted with everything,” she says, adding: “I’m swaying towards Labour just now.”

She is hopeful that Scotland will eventually become an independent nation and join the European Union, but says she doesn’t believe it is time for independence “just yet” because “we’ve got so many other things to solve”.

Polls suggest there are a lot of Ashleigh Morrisons in this election. If that is correct it will worry the SNP now and could cause Labour a headache in the future.

Either way, it seems unlikely that the constitution will suddenly vanish as an issue in Scottish politics, 25 years after devolution, and a decade after Scotland voted decisively, although not overwhelmingly, to remain part of the United Kingdom.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSince then, the two parties that have profited most from the tussle between independence and union have been the SNP and the Conservatives, who have both used it to fire up their supporters.

There is actually a majority in the Scottish Parliament in favour of a second independence referendum, but MSPs cannot lawfully hold one without the consent of Westminster, which has not been forthcoming.

Mr Swinney says if the SNP wins a majority of Scottish seats in the House of Commons at this election, it will be another mandate for a referendum, although the Conservatives and Labour have dismissed that idea as a non-starter.

Both parties have been emboldened by an apparent slump in the SNP’s popularity amid changes of leader, problems with public services and controversy about certain policies, particularly in relation to gender.

The SNP has also been dented by a lengthy police investigation into its “funding and finances”, which has resulted in an embezzlement charge for its former chief executive, Peter Murrell, the husband of former first minister Nicola Sturgeon.

“I would be the first to admit, James, that the SNP has had a pretty rough time over the last year or so,” Mr Swinney told me at the start of the campaign, barely a fortnight after he had taken over from Humza Yousaf as party leader and first minister.

It’s not just the past 12 months that have been difficult for his party. Ailsa Henderson, professor of political science at Edinburgh University, says the SNP’s slide in the polls actually began in 2021.

She also notes that support for independence has “absolutely not moved” during the last three years and remains relatively high.

Prof Henderson says that support has very rarely dipped below its “natural floor” of 45%, and suggests that we are now seeing a “decoupling” of support for independence and support for the SNP.

PA Media

PA MediaThis also presents a challenge for Labour, which knows that to regain its advantage in Scotland, it needs to satisfy pro-independence voters who switched to the SNP around the time of the referendum.

The Labour leader, Sir Keir Starmer, hopes Scottish seats can help him win a parliamentary majority and become prime minister – although the SNP points out that if current polling is accurate, he is on course for a landslide victory without needing any Scottish seats at all.

Either way, rather than addressing the issue of independence head on, both Sir Keir and the Scottish Labour leader, Anas Sarwar, are trying to talk about the constitution as little as possible, focusing instead on their pitch that only Labour can restore stability to the UK.

That is a dig aimed not just at the Conservatives, who have been in charge of the UK government in London for 14 years, but also at the SNP, which has been at the helm of the devolved Scottish government since 2007.

“The defining question of the last decade, the currency of our politics, has been identity, culture and belonging,” says Douglas Alexander, who served as a cabinet minister under Labour prime ministers Tony Blair and Gordon Brown.

But at this election, he argues, voters are focused on how they can eject Conservative Prime Minister Rishi Sunak from 10 Downing Street.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesLabour hopes success at this election will be a springboard for the next Scottish parliamentary poll, in 2026, when it will try to regain control of the Scottish government for the first time in 19 years.

Prof Henderson says the first part of the Labour strategy appears to be working, with polls suggesting that the Tories are on course for their worst performance since 1928.

“As UK Labour’s polling fortunes have increased in Britain as a whole, driven largely by improved performance in England, then we’ve been seeing decreasing support for the SNP in Scotland,” says Prof Henderson.

Douglas Alexander says the SNP’s “powerful vote-winning story” in previous general elections is not working in 2024.

It is a story he knows all about, from bitter personal experience.

In 2015, he lost Paisley and Renfrewshire South (majority 16,614) to the SNP’s Mhairi Black as the nationalists became the third biggest party at Westminster, winning an extraordinary 56 of 59 Scottish seats.

Labour, the Liberal Democrats and the Conservatives were left with just one each.

At the last general election the position was SNP 48, Conservatives six, Liberal Democrats four, and Labour one.

Boundary changes have reduced the number of Scottish constituencies from 59 to 57, and Labour is estimated to start in second place to the SNP in 27 of those seats.

Almost all of them are in the post-industrial lowlands, stretching from the Firth of Clyde in the west to the Firth of Forth in the east, where Labour was dominant in every general election from 1959 until 2010.

“It’s definitely a new phase for both the independence movement and the unionist side,” says Liz Lloyd, who was chief of staff to SNP First Minister Nicola Sturgeon from 2015 to 2021.

She points out that there has not been a Labour government since the independence referendum in 2014.

If Sir Keir Starmer becomes prime minister, she adds, he will be under immediate pressure to prove to voters interested in independence that he can create real change within the union, despite his promise to stick to Tory spending plans.

For Ms Lloyd, that means delivering improved economic growth along with better jobs and housing for young people.

It would not be easy. Independent experts have warned both the Conservatives and Labour that their manifesto promises cannot be delivered without tax rises, cuts to public services, more borrowing or a combination of all three.

Mr Alexander concedes it will be “a challenge to turn around a country where everything costs more and nothing works”, but he insists that Labour is “well placed to answer that challenge”.

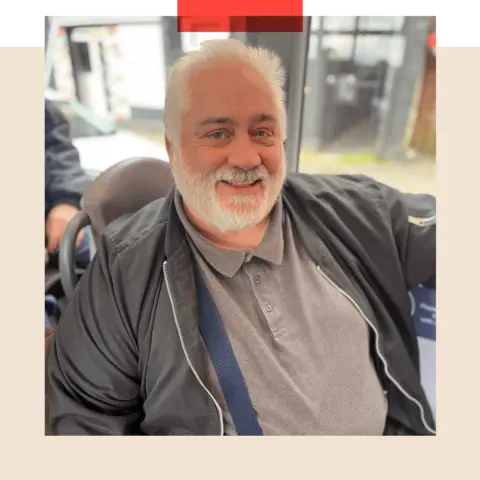

On the number 61 bus, which links working class suburbs in the north-west and east end of Glasgow, Danny Doyle is not convinced. He will be voting SNP.

“My dad was a Labour man and his dad was a Labour man,” he says. He believes the party has changed its values. “Just now, if you’re voting for Labour or you’re voting for Tory, there’s no difference as far as I’m concerned.”

Ms Lloyd says the danger for Sir Keir is that he has alienated people in Scotland by moving too far to the right in order to accommodate voters in England who shifted from his party to the Tories in 2019.

If the somewhat more left-wing Scottish electorate is unimpressed by his premiership, then Ms Lloyd reckons independence could be back on the agenda in the 2026 Holyrood election – or, perhaps more likely, at the following general election.

“If independence support doesn’t decline under a Labour government in any significant way, then I think it really confirms that the question needs to be resolved by some form of constitutional mechanism in the future,” she says.

Who can I vote for in the general election?

Prof Henderson agrees that Labour’s strategy of keeping quiet about the constitution can only take it so far.

“It’s OK to kind of dodge the question in a UK election,” she says, “but after that win, you are going to start to need an answer in terms of what your vision of the constitutional arrangements for the state are.

“Staying silent on it isn’t really going to help.”

Gordon Brown, Labour prime minister from 2007 to 2010, has made a similar argument, warning fellow unionists: “In the long run, the forces pulling Britain apart are greater than the forces holding it together, unless something is done about it.”

Mr Brown’s blueprint to address the issue, commissioned by Sir Keir and published in December 2022, was entitled “A New Britain”.

The former MP for Kirkcaldy and Cowdenbeath’s proposals have not been adopted wholesale by the Labour leadership.

The party’s manifesto does promise to strengthen the principle that Westminster should not legislate on devolved matters, and aims to improve co-operation between the UK’s various governments.

But Mr Brown’s most striking plan – replacing the House of Lords with an elected second chamber known as an Assembly of the Nations and Regions – appears to have been kicked into the long grass.

PA Media

PA MediaWhen it comes to independence, Labour’s largely unspoken argument appears to be that it would be impractical and unaffordable just now, involving destabilising change to the country’s currency, borders, public services and more.

At the same time, the SNP is stressing what it regards as the practical case for independence, as an escape route from a stagnating United Kingdom.

It says entrenched low growth, low productivity and high inequality have been compounded by cuts to public spending and the UK’s departure – against the wishes of a majority of Scottish voters – from the EU.

This is not the “existential nationalism” expressed in the fighting talk of the Declaration of Arbroath but the “utilitarian nationalism” of the late Neil MacCormick, one of the most influential thinkers in the SNP’s 90-year history.

In a 1970 essay Sir Neil, as he would later become, proposed independence as “the best means to the well-being of Scottish people”, adding that it “would have to be preceded by devolution”.

He would surely be delighted to see polls that not only indicate a relatively high and stable level of support for independence, but also point to even higher levels of support among younger voters.

In the past decade, says Prof Henderson, while older voters have become more opposed to independence, “the youngest members of the electorate have become markedly more supportive”.

Not only that, but the average age at which voters shift from supporting independence to opposing it has risen from around 40 to around 50, she adds.

Prof Henderson cautions that “demography is not destiny”, noting that a similar pattern in the Canadian province of Quebec was eventually reversed and, nearly 30 years after it narrowly rejected independence, Quebec remains part of Canada.

Nonetheless, the Scottish polling gives heart to supporters of the idea and causes some concern for its opponents.

If Labour does win this election, Scotland may be embarking on a new political phase, with voters weighing up their position on the constitution not first and foremost by scrutinising the SNP’s plans but by closely assessing whether or not they are prospering within the UK.

Half a century after the SNP outlined the principle of utilitarian nationalism, its opponents may be about to put utilitarian unionism to the test.

- Douglas Alexander is running in this election. A full list of candidates in the Lothian East constituency, which he is contesting, is available here.

BBC InDepth is the new home on the website and app for the best analysis and expertise from our top journalists. Under a distinctive new brand, we’ll bring you fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions, and deep reporting on the biggest issues to help you make sense of a complex world. And we’ll be showcasing thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. We’re starting small but thinking big, and we want to know what you think – you can send us your feedback by clicking on the button below.