How does Labour want to tackle poverty?

Getty Images

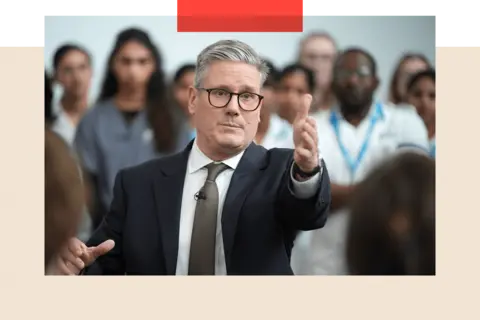

Getty ImagesWhen Keir Starmer was running to be leader of the Labour Party, the second of his 10 pledges contained an unambiguous ambition to “abolish Universal Credit and end the Tories’ cruel sanctions regime”.

The Labour Party’s manifesto for the 2024 general election reads very differently. The commitment was dropped in 2023, and now the party simply talks of being “committed to reviewing Universal Credit so that it makes work pay and tackles poverty”.

About three weeks before the 2019 election, Keir Starmer posted a tweet. “I’m proud to be a patron of my local food bank,” he wrote. “I’ll be even prouder when, under a Labour Government, food banks are no longer needed.”

With food bank use at a record high and no imminent action planned on Universal Credit, some Labour Party candidates I have spoken to and other poverty campaigners fear the party is not being explicit enough about what it would do to help the least well-off.

Getty Images

Getty Images“We’re not talking about poverty,” says Rosie Duffield, who is standing to be re-elected as a Labour MP in Kent. Ms Duffield now speaks with almost unique candour amongst Labour candidates, the after-effect of her very public tangle with Keir Starmer on transgender issues.

She adds: “We should be aiming to eliminate it, particularly child poverty, as soon as we possibly can. We are scared of promising too much that might harm our poll lead, but we have to be the change the country needs.”

In 2009-10, the Trussell Trust handed out just under 41,000 emergency food parcels. In the last financial year – 2023-24 – that figure had increased to 3.1 million, a record high. The British Social Attitudes Survey shows 73% of people believe there is “quite a lot” of real poverty in Britain, the highest recorded level in almost four decades of asking the same question.

The Labour manifesto pledges to ”develop an ambitious strategy to reduce child poverty,” including introducing free breakfast clubs in every primary school. It also says it wants “to end mass dependence on emergency food parcels” but does not specify how.

“We were encouraged to see that commitment,” says Helen Barnard, director of policy at the Trussell Trust, the country’s largest provider of food banks. She says the party’s promises to build social housing and strengthen job security has the potential to reduce poverty. But “what we need to see is fast action about how they’ll tackle hardship, and in their very first budget (if they win the election)”.

The party’s manifesto in 2019 had an entire section on tackling poverty and inequality, but in the 2024 manifesto the party’s focus on making people better off is framed round the more general goal of kickstarting economic growth. This is not a one-off – in the four party conference speeches Mr Starmer has made as leader, he has never talked about tackling poverty and inequality specifically.

Labour are of course happy to talk about the problems they say the Conservatives have caused, including the soaring use of food banks. There is no reference to tackling poverty in the UK in the Tory party manifesto. Instead, the party says it will cut £12bn from the projected increase in the welfare budget by reducing the benefits paid to disabled people in particular; saving that amount, says the Institute for Fiscal Studies, will be “difficult in the extreme”, although it acknowledges “cuts are certainly possible”.

A number of those I spoke to said they believed that, if Labour won, it would be bolder in power on measures specifically aimed at helping those least well-off than it has been in public so far, and urged people to look at Labour’s previous record in government, particularly in reducing child poverty.

But with the party likely to inherit tight economic circumstances, one senior Labour candidate admitted it was “struggling to provide hope” for low-income households.

Ian Byrne, who is also a Labour candidate, led a “Right to Food” campaign in the last Parliament. He has produced an election video in which he says that “when we get in power, we must eradicate food banks”.

“MPs see the impact of poverty in their constituencies on a daily basis – we have an unbelievable opportunity to set out a different pathway,” he adds.

‘Biggest driver’

Labour are determined to avoid accusations of being financially reckless and this has extended to refusing to scrap the “two-child” policy that says parents can’t get key benefits for their third or subsequent children born after April 2017.

The cap has been called the “biggest driver” of poverty among children by the Child Poverty Action Group. It currently affects two million children. The IFS calculates that by the end of the next Parliament, an additional 670,000 children will be impacted and says that scrapping the policy would cost £3.4bn, the equivalent of “freezing fuel duties for the next parliament”.

Keir Starmer has said he would like to scrap the policy, but that “I’m not going to put a date on these things.” The SNP believe his caution has given them an opportunity to seize traditional Labour territory in Scotland. It is calling on a future Labour government to scrap the two-child policy. It has also introduced the Scottish Child Payment – worth £25 per child, per week, to low income households – which is expected to prevent 100,000 children from falling into poverty; initial research suggests it is also reducing the need for food banks among some households.

Unlike Labour, the Liberal Democrats say they would immediately scrap the two-child policy and they have explicit commitments to reforming Universal Credit – reducing the waiting time for the first payment from five weeks to five days.

Labour’s stance on the “two-child” policy has caused internal unease. “It was profoundly disappointing that Keir committed to that policy,” says Rosie Duffield.

Sir Stephen Timms was – until the election – chair of the Work and Pensions Select Committee. He also served as Chief Secretary to the Treasury during Tony Blair’s government.

Overall, he thinks the leadership’s stance is appropriate. “I think the party is in a sensible place. It’s quite reasonable that the details aren’t set out. Big changes do need to be made but the economy needs to be repaired.”

However, he is not supportive of the “two-child” policy. A future Labour government will face “huge pressure to scrap the policy,” said Mr Timms. “I’d like to see it scrapped.”

For some in Labour, what is particularly galling is to see some on the right also calling for the policy to be ditched. Both Suella Braverman, the former Tory Home Secretary, and the Reform UK leader, Nigel Farage, have said the two-child cap should be removed. Reform also says it would raise the level at which income tax kicks in to £20,000, benefitting low-paid workers.

Missing link

Aside from policy specifics, there may be a deliberate shift in positioning too from those at the top of the Labour Party, regardless of how much money is available.

Wes Streeting, the party’s health spokesman, told the Independent newspaper that “the answer to child poverty, ultimately, is not simply about handouts. It is about a social security safety net that also acts as a springboard that helps people into work… that makes the cost of living affordable for everyone.”

And writing in the Sunday Telegraph recently, Keir Starmer said: “Serving the interests of working people means understanding they want success more than state support.”

But for some there is a missing link. Helen Barnard from the Trussell Trust says: “When you look at the ambitions that Labour have laid out around education, around the NHS, all of these are really vital. (But) we would argue that all of them will be held back by leaving so many people experiencing destitution, poverty and hunger.

“Unless we are releasing people from that, they can’t take those opportunities to move into work or to move further into education, because they’re struggling day to day to get by.”

The Joseph Rowntree Foundation says the level of Universal Credit is at a historic low, after years of squeezes, freezes and cuts. It calculates that the current basic rate of £91 a week for a single person aged 25 or over is £30 a week less than what’s needed to live on.

The UN’s special rapporteur on extreme poverty, Olivier De Schutter, has gone even further, suggesting Universal Credit rates should be increased by at least 50% “in order to provide a decent standard of living”. Benefit levels have risen in line with inflation in only five of the past 14 years.

The Lib Dems say they’d review annual benefit levels during the next Parliament to ensure they are high enough for people to live on.

However Liz Kendall, the shadow work and pensions secretary, told the Times a few weeks ago that she wanted “a more effective benefits system” rather than a more generous one.

With the Labour shadow cabinet asking for “low or no cost” solutions, according to one anti-poverty campaigner, the former Prime Minister Gordon Brown has offered some alternatives. He has suggested that a £3bn anti-poverty fund could be established through changes to the Gift Aid scheme and the Bank of England.

Tackling poverty is often difficult and expensive, which may explain Labour’s caution.

What hope it can offer Britain’s poorest comes more in the promise of general economic growth than in policies targeted specifically at them.

BBC InDepth is the new home on the website and app for the best analysis and expertise from our top journalists. Under a distinctive new brand, we’ll bring you fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions, and deep reporting on the biggest issues to help you make sense of a complex world. And we’ll be showcasing thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. We’re starting small but thinking big, and we want to know what you think – you can send us your feedback by clicking on the button below.