Is this really the TikTok general election?

BBC

BBCSnarky, silly and sometimes downright rude – TikTok has breathed new life into the political meme. But how much influence is it actually having on the general election?

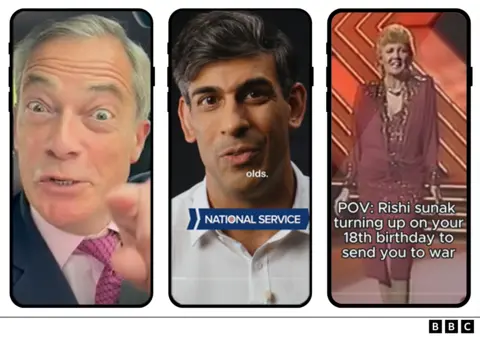

Nigel Farage is the unlikely breakout star of TikTok at this election, with a five second clip of him mouthing the words to an Eminem song – “guess who’s back?” – pulling in more than eight million views.

The 60-year-old Reform UK leader was not previously known for his love of hip-hop – the clip was the brainchild of his young social media team.

But other Farage-branded content is regularly outperforming material produced by his political rivals and his personal account has more than twice as many followers as Labour, the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats combined.

The Reform UK account has fewer followers, and far fewer videos of Mr Farage playing up to the cameras, but with 197,000 followers is still more popular than the Tory offering.

The Tories’ best-performing clip was the first one they produced, entitled “this will change lives,” in which Rishi Sunak spends 50 seconds eagerly promoting his national service policy. This got a creditable 4.2m views.

But Labour’s 11-second takedown of it got 5.1m views.

This featured archive footage of showbiz legend Cilla Black belting out “Surprise, Surprise” with a caption that reads: “Rishi sunak turning up on your 18th birthday to send you to war” (the lower case S in Sunak presumably adding to the rough, authentic feel).

It was a version of an existing TikTok meme – something Labour has been adept at doing, says Sam Jeffers, of Who Targets Me, which tracks political advertising.

“Labour have people who are dripping in internet culture, the way they format videos, the way people talk.

“It is so clear that they have got people who are just incredibly switched on.”

Antler Social

Antler SocialVic Banham, CEO of TikTok ad agency Antler Social, was less impressed.

“It makes me question their sincerity and what they are going to be like in government,” she says of Labour’s efforts, although she concedes “they are all as bad as each other”.

“It feels like your dad getting on TikTok to get down with the kids. It feels like a strategy that is not authentic.”

There is no doubt that brash, attention-grabbing clips get results, says Ms Banham, but she adds: “On TikTok there is a way to reach that younger audience without bringing that childish, playground bullying energy.”

She says she would like to see manifesto policies explained in a jargon-free way by people “who look and feel like the people they are trying to reach”.

The Lib Dems and Greens have played it straighter than the big two on TikTok, although the Lib Dems have spoofed the Simpsons and Spongebob Squarepants to attack the Tories.

But like their larger rivals they have mainly relied on party leaders to deliver their core messages.

The Tories did use “ordinary people” to comment on the national service policy, but the universally glowing reviews in the clip raised unfounded suspicions in the comments that they were actors.

TikTok does not accept paid political advertising, so it is a cheap way of reaching a large, youthful audience.

But it is dwarfed by Facebook and YouTube when it comes to audience reach.

More than 90% of online adults in the UK use Facebook and YouTube, according to Ofcom, compared with 48% for TikTok.

For this and other reasons Sam Jeffers believes the hype about this being the first TikTok election is massively overblown.

“’The TikTok battle’ is a narrative in this campaign that simply won’t die,” he says.

“It’s filling space because the ‘AI election’ never showed up.”

The real battle is being played out on Facebook and YouTube, he argues, where the main parties are ramping up their spending as the campaign enters its final stretch.

The Conservatives are spending most of their budget on Facebook, where they can use targeting tools to get their message out to core, older voters across the UK.

Labour is also spending big on Facebook but unlike the Tories they are pumping money into YouTube and Google ads as well, targeting them at specific towns and cities.

Some platforms, such as X, formerly known as Twitter, do not publish spending records so it’s difficult to get the full picture.

But according to Who Targets Me’s analysis of available social media ad libraries, £4.2m has been spent on election ads on Meta, which includes Facebook and Instagram, in the first month of the campaign.

Meta ad spending doubled between 16 and 22 June, largely thanks to a significant increase in Tory spending, although they remain slightly behind Labour.

Reform has also ramped up its Meta spending in the past week and started pouring money into Facebook ads in Nigel Farage’s name.

Like the Green Party, Reform is concentrating its resources on far fewer seats than the bigger parties.

Since the election was called the Greens have spent more than £39,000 on Meta adverts for their co-leader Carla Denyer in Bristol Central, but all the adverts began their run before the beginning of the regulated election spending period on 30 May.

By contrast, her co-leader Adam Ramsay spent £932 on Meta ads in the same period.

In Scotland, the SNP has largely eschewed TikTok and is being outspent by Scottish Labour on Meta.

But it is a very different political landscape. One of the SNP’s core messages is “rejoin the EU” – something that you would not hear from any party south of the border.

Scottish Conservatives’ advertising has focused a great deal on highlighting seats where they claim only they can beat the SNP.

In Wales, since the start of campaigning, Labour have spent almost as much on the softer tone of adverts of their Wales’ Future brand (over £74,000) as with Welsh Labour (over £80,000) on Meta platforms.

These sums are significantly more than their rivals – neither Plaid Cymru or Welsh Conservatives has spent more than £5,000 on their main accounts. Plaid’s advertising on Meta platforms has yet to exceed £1,000 for any single candidate.

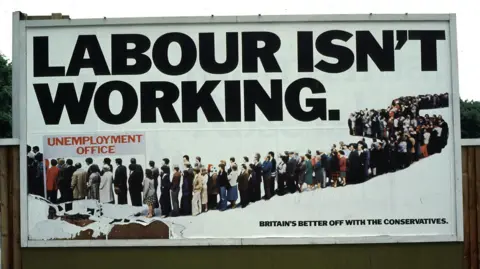

At one time all of this money would have been spent on buying huge poster sites in marginal constituencies.

Now, if the parties bother with them at all, posters are unveiled to the media and then driven around central London for a few hours on the side of a van.

The clever, stinging attack lines and dubious claims about rival party policies that made some election posters iconic, or notorious depending on your point of view, now come in meme form.

“It is the modern day billboard,” says veteran PR expert Mark Borkowski.

“You are playing with emotions not facts and figures, playing with how people feel about it.”

He says he is concerned about the “amount of bots being used” to distribute content and claims there is “a lot fakery” going on, adding “it was always going to be a dirty election”.

In a fiercely-competitive environment, he adds, “who has the best memes wins”.

Political advertising in the UK is not regulated – you can’t complain to the Advertising Standards Authority about misleading claims. It is down to rival parties to rebut them as best they can or fact checkers to debunk them, as BBC Verify did this week with a Tory Facebook ad on Labour’s pension policy.

Social media does at least offer parties ample space for detailed retaliation, although if TikTok has taught us anything it is that a five-second clip of Cilla Black might be more effective.

Additional reporting by Alex Murray