‘Who do you trust?’ People at this food bank say election offers them little hope

BBC

BBCPam is used to poverty and desperation, but she’s never known it this bad. She runs the Rock Foundation Food Bank in Grimsby. “We are feeding 800 people a week, it was 300 five years ago,” she says.

The food bank is in a derelict public toilet, and the food is passed out through a small hatch. “At another food bank someone pulled a knife out,” Pam explains. “We’ve done it in a way that we can shut it down quickly if anything was to happen.”

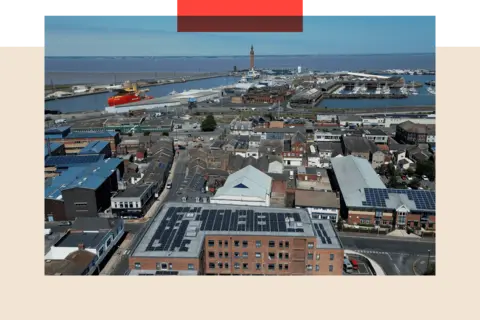

We counted at least six food banks in this square mile of East Marsh, which is home to 10,000 people. It‘s not only one of the most deprived wards in Grimsby, but also in the top 1% of most deprived places in all of England, on almost every single metric – income, employment, health, crime and education.

The average household income here is just £22,200. The average years a man could expect to live in good health has just dipped below 60 years.

One woman at the food bank, struggling to walk, shows me her fruit. How important is this to you, I ask her. “If I didn’t have it, I wouldn’t eat.”

As well as the food bank, Pam gives out warm meals, free haircuts and advice on benefits. It’s like a shadow welfare state, but one that relies on goodwill. “It’s horrible, you feel so desperate,” she says.

Each bag is meant to last three days, but they can’t give out as much food as they used to, she says. “We’re just putting a sticking plaster on what the real issues are.”

Just around the corner on Freeman Street, vaping shops line up alongside cafes and newsagents, but you cannot help but notice the boarded-up shops. The town’s commercial vacancy rate is nearly three times the English average – more than one in four premises here are empty.

It’s in stark contrast to the days when Grimsby had a thriving fishing industry and port. Sitting outside the food bank is Patrick, off work with ill health. He has witnessed decades of decline, and he is despondent. “Everything has gone and been destroyed – the fishing, the farming, everything’s gone.” There’s an election coming, so I ask: can politics fix this? No, says Patrick. “It’s all gone and not coming back.”

Pam also says she has “zero faith” in politicians. “It’ll be us who fixes this, the charities,” she says. I ask Pam who she will vote for, but she says she doesn’t know. “Who do you trust?” she wonders.

We meet Jessica walking home after buying a bit of food for her children, Isabelle 3, and Lucas, who is 18 months. Jessica is a full-time mum living on Universal Credit, and money can be tight. “I go without so my kids are fed,“ she says. “I’m not able to provide everything my kids want but I’m able to provide what they need. They are missing out on school trips because I’ve got more important things like food and stuff to pay for.”

Jessica isn’t struggling alone in Grimsby, where about one in four children live in poverty, according to the Office for National Statistics.

I ask Jessica when was the last time she went out by herself, a night out or cinema? She pauses, and guesses it was over a year ago. “It brings you down. You feel isolated.”

She hopes when they are older, her children won’t have to struggle, “I want Lucas to be able to thrive and be able to achieve anything he wants to and Isabella, my eldest, to achieve everything that she wants in life, be happy and live every day without worrying about the world.”

The poverty we saw in Grimsby is acute but not unique. Across the UK, there are around 1,700 food banks, and the number of parcels delivered by one of the leading providers, the Trussell Trust, has doubled since the last election to over three million.

Yet there is investment coming, and change is under way. The town has received £20m of government money for a new leisure complex including a five-screen cinema and a market hall at Freshney Place. The renewable energy sector has also brought new life to the port, employing about 2,000 people, and many of those are skilled jobs with the potential of higher wages.

Spades are in the ground, but it will be a while yet until it is finished. And many of the high-end engineering jobs are out of reach of local people. Change doesn’t happen overnight.

Philip Jackson, the leader of North East Lincolnshire Council, says there are job opportunities and skills training for young people, but despite the changes, many local residents do not feel connected to them.

“We do have a messaging problem. People do not see the windfarms, they can’t see over the fences into the port.” There’s work to do, he says, to make all of Grimsby feel included.

On Freeman Street we meet Dom, 29, with a handful of Xbox games. “I’ve pawned these games, I’ve just bought them back.” He explains that he got about £5 for them, to pay for food, but had to pay more to get them back.

Dom says that he’s struggled for a long time, but the cost of living crisis broke him. “It’s ridiculous, I’ve been made homeless three times this year.”

He says he had a zero-hours contract in a fish-packing factory, but his shifts went down as his bills went up. “My rent kept on going up, three times in six months, and the more I paid in rent, the less I could eat.”

“It messed me up.“ His lowest lowest moment, he says, was waking up in hospital after a failed attempt to take his life.

He now lives in the Humber YMCA. It’s modern, safe, a place where he can rebuild his life. “I just want to be able to live, go out and have a drink or food. All I’ve been doing is surviving and pushing through, that’s all I can do. It’s survive or die.”

There is hope in the poorest of places, still. In the heart of East Marsh, we tour a row of terraced homes with Josie Moon, who is on a mission to transform the area with her group East Marsh United. Put simply, she loves Grimsby and cares about its people.

As we walked past an abandoned couch and boarded-up homes, she reels off her to-do list for whoever wins this election: “You’re talking about homes infested with rats, mould, damp, poorly paid jobs, health and disability issues.”

She has already secured £500,000 in funding, and Josie excitedly shows me the derelict homes the group has bought to rent out to local families. “There’s a lot of opportunity coming, but it takes a long time. It takes a long time to rebuild and to replace what’s been lost.”

What’s apparent is that Grimsby needs its highly educated young people to stay in the town – people like Jess, a 26-year-old university graduate. She has three jobs to help pay bills, but irregular hours can mean difficult choices.

“I don’t have a TV, I don’t have a washing machine at home, I don’t have wi-fi at home, I don’t smoke or drink very often. So, those outgoings aren’t going out.”

She is very much a modern grafter, making extra cash baking pastries and cupcakes and advertising them on Instagram. She wants to succeed in Grimsby, and she believes she has a future here.

“I’m rich in many ways, in that I have I have friends and I have a community of people.” But Jess also wants more support for the town. “We need help.”

One of Jess’s jobs is at Docks Academy, a pub, brewery, and live music venue. It’s based in a former church on the edges of East Marsh that was built in 1874 and was once at the heart of a community of thousands of dock workers.

It’s a place reborn. Owner Will Douglas moved from London to set it up. “It’s vital, we’ve brought brewing back to Grimsby after a break of 50 years and we’re training people to brew.”

Will’s family are from Grimsby and he desperately wants the town to succeed: “I think it’s really important for young people of this town to see that there are great things happening, things that they want to stick around in Grimsby for.”

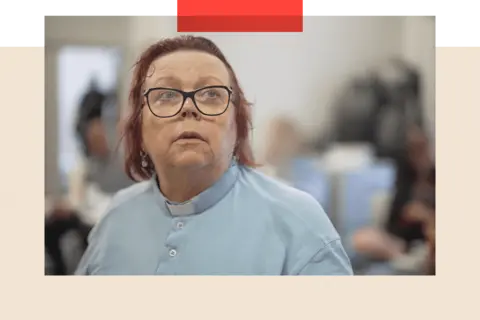

But waiting is hard. Back on Freeman Street, we visit our second food bank of the day and inside a sweltering kitchen on one of the hottest days of the year, we find a worried Reverend Kay. “There’s more people coming in every week, we just cannot get enough food in to supply the need,” she says. She shows me the empty shelves that were full of vegetables at the start of the day.

The We Are One food bank can feed up to 150 people in a day. The cost of living crisis has stripped people of their dignity, she says.

Throughout our time in Grimsby, many we spoke to told us they were not going to vote or simply had no faith that politics could fix their lives. It’s a thought I put to Kay – was this a risk to our democracy, I ask. She becomes visibly upset.

“It makes so angry,” she says. “My grandad was one of those that fought for unions, fought for the strength of the working man, and it’s just been totally disenfranchised.”

At the last election, Grimsby had one of England’s lowest voter turnouts – just 53% of those eligible to vote did so, compared with the average of 67.5%.

Still, Kay is determined: “I’ll die before I stop. It has to be done. It does wear people out, and I think a lot of people have actually given up, but I’ll die fighting.”

It’s clear that significant investment is coming into Grimsby, but the scale of the challenge to ease the cost of living crisis and tackle deep rooted poverty, is also apparent.

All the main parties are pledging to help. For those we spoke to in Grimsby, struggling day-to-day, it’s a promise they are depending on.

BBC InDepth is the new home on the website and app for the best analysis and expertise from our top journalists. Under a distinctive new brand, we’ll bring you fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions, and deep reporting on the biggest issues to help you make sense of a complex world. And we’ll be showcasing thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. We’re starting small but thinking big, and we want to know what you think – you can send us your feedback by clicking on the button below.