Families seek answers over pregnancy test drug

BBC

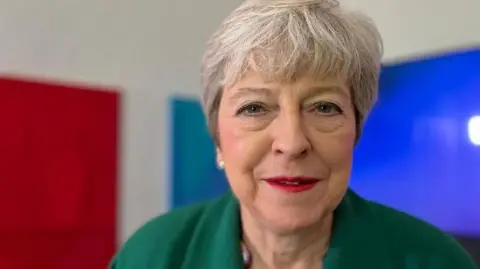

BBCAn “abuse of power” 40 years ago has left families fighting for truth over the cause of birth defects, according to former Prime Minister Theresa May.

The health service and government of the time “defended itself, rather than trying to find the absolute truth for people” about whether a hormone pregnancy test caused malformations, stillbirths and abortions, she said.

The drug company involved denies any link between Primodos and birth defects, and legal cases have been dismissed in the High Court.

But families have continued to lobby for recognition and support.

“Some children have suffered incredibly during their lives and it is ongoing – it’s not finished,” said Mrs May, who stood down as an MP at this month’s general election.

Primodos contained synthetic hormones and was used between the 1950s and 1970s as a pregnancy test.

Last year a High Court case seeking damages was thrown out after a judge ruled there was no new evidence linking the tests with foetal harm and “no real prospect of success”.

But Mrs May feels the thorny issue of evidence is not clear cut.

In 2017, a government review by an expert working group said there was not enough evidence to prove a link between hormone pregnancy tests (HPTs) and birth defects.

“The expert working group actually said ‘on balance’ there wasn’t a causal link between Primodos and birth defects,” said Mrs May.

“But that meant that there was evidence on both sides and they’d come down on that side of the argument. So I think that does need to be looked at again.”

Pharmaceutical company Bayer said it had “sympathy for the families, given the challenges in life they have had to face”.

“Previous assessments determined there was no link between the use of Primodos and the occurrence of such congenital anomalies, and no new scientific knowledge has been produced which would call into question the validity of that conclusion,” the company said.

The Department of Health and Social Care said: “The government would review any new scientific evidence which comes to light.”

Mrs May commissioned Baroness Cumberlege to review the use of Primodos, along with vaginal mesh and sodium valproate.

That report was published in 2020 – prompting apologies from the UK and Welsh governments – as it concluded that the use of HPTs should have been stopped in 1967 because of the “suggestion of increased risk” by researchers.

It added that further opportunities for action were missed in 1970, 1973 and 1974.

Indeed, the official use or “indication” for Primodos was changed in 1970, meaning it was no longer to be used as a pregnancy test.

However, the company that manufactured the drug, Schering, wrote in October 1977 that, in the previous 12 months, thousands of women had still been prescribed it as a pregnancy test.

Women like Margo, Helen, Barbara, Kathryn and Jean were given two Primodos tablets by their doctors to establish if they were pregnant, during the 1960s and 70s.

Their experiences differ, but their strong belief is that Primodos was at the root of devastating consequences.

Each spoke of the guilt they felt at taking a tablet that was given by their doctor.

Margo Clarke, from Bridgend, was given Primodos in 1970, which confirmed she was expecting her first child, Adrian. But she said from the minute he was born he was a sickly child.

“And the bigger he got, the worse he got,” she said, recalling times when his younger brother would need to get out of the pushchair, to allow six-year-old Adrian to be pushed, as he was too unwell to walk.

“He couldn’t play, he couldn’t run around, or play football, because he would just be very breathless,” she said, adding that his lips would turn blue.

“It was so distressing to see how unwell he was.”

Margo Clarke

Margo ClarkeHe was eventually referred to a specialist and was diagnosed with a hole in the heart, but the family were told he was not ill enough for surgery.

“Because Adrian was mixed race they would say the blue lips were due to his colour and the fact that he couldn’t run around was because of his West Indian heritage and his temperament,” Margo said.

“I was called over-anxious, neurotic, and I got to the point where I thought my son was going to die before they made an appointment to see the diagnostic surgeon.

“When she [the surgeon] turned up she was horrified that he had been left so long and said he was very lucky to still be alive because he could have dropped dead at any moment.

“I could see him literally withering away before me and he had no quality of life whatsoever.”

Within a month he was taken to London for open heart surgery.

“To say I felt relief is an understatement, because I felt such anxiety over those years, thinking nobody’s listening to me.”

She said a month after the operation, Adrian was running on the beach with a kite.

“It was the first time I’d seen him enjoying himself and not having to sit down because he was breathless.”

Helen Elkes

Helen ElkesNow 53, and having spent more than 30 years working as a nurse, Adrian can still vividly remember his early childhood.

“I couldn’t do anything with my friends and was always in with the school nurse, needing a lie down.

“I also remember being in hospital for a month, a long way from home and I was very frightened.”

However, he said he was “one of the lucky ones, because I’ve had a relatively normal life since”, adding that “some of the victims in this are much worse off”.

Helen Elkes was given the tablets by her GP in Wrexham in March 1970.

She recalled being told they should not be taken by women who were not young and healthy, but as a healthy 24-year-old, she was given the two tablets that confirmed her pregnancy.

Beccy was born in November 1970 and has several diagnoses, including cerebral palsy, autism, and has limited speech.

“We didn’t know she was disabled until she was 12 months old,” said Mrs Elkes, who now lives in the West Midlands.

“The effect on our family has been all consuming.

“Beccy lives in care, she can’t look after herself at all. She still comes home every two or three weeks, but I’m 78 and can’t possibly look after her full time, and it breaks my heart.

“I feel terrible guilt that I can’t look after her all the time.”

Barbara Stockley

Barbara StockleyBarbara Stockley had recently married and moved to Cwmbran, Torfaen, when she was given Primodos in 1965.

Her son Andy can’t live independently and needs two-to-one care, which 82-year-old Barbara and her husband coordinate with five personal assistants on a rota.

“We’re classed as a micro-employer, so we have to insure ourselves and handle all the finance like an agency,” she said.

“It takes two hours to get him ready in the morning because we have to do it at his pace.”

She said Andy lived in residential care as a young man “but he wasn’t being treated properly” and had been home since he was 22 – he’s now 58.

Kathryn McCabe

Kathryn McCabeKathryn McCabe now lives in Powys, but was living in St Helens, Merseyside, when she took the HPT in 1973, aged just 18.

The following year her baby was stillborn, with distressing malformations. While she went on to have two healthy sons, her first pregnancy had a profound impact.

“It’s awful to go through all of that and come home with nothing,” she said.

“You look at others with their prams and wonder why they have their babies and you don’t.”

She explained learning about the Cumberlege review and the suggested link with Primodos relieved some of the guilt she has felt over the years.

“It wasn’t something I had done – because you automatically think it’s your fault,” she said.

Jean Baker

Jean BakerJean Baker was delighted to find out she was pregnant in 1970.

As a 27-year-old nurse she knew the tell-tale signs, but her GP suggested the tablets would confirm it.

“For me it was my only chance with my husband to have a child,” she said, explaining the pregnancy was unplanned because her husband did not want to have children.

“I was delighted, but 10 days later [after taking Primodos] I aborted the child.

“The doctor should not have advised me to take the tablet, there was already advice not to prescribe it to pregnant women, so this was a terrible mistake on his part.”

The 85-year-old from Menai Bridge, Anglesey, said losing the pregnancy had a life-long impact.

“I have mixed feelings because I didn’t have a disabled child, as many others did, but since my husband died I’m totally alone.”

Bethan Dickson

Bethan DicksonBethan Dickson’s mum, Lon took Primodos in 1968 when she was living in Newport, and Bethan was born in September that year.

She has needed several operations on her feet over the years, as her toes “were growing across my foot, rather than straight”, she said.

She said it was only when she took part in the evidence gathering for the Cumberlege review that she fully considered the psychological and emotional impact.

“I knew I was in pain all the time I was walking – you can see the scars from surgery. But what you don’t see is the exclusion I felt. And that was much deeper than I realised.”

She said both she and her mother have felt guilt – her mum for taking the tablets, as advised, and for Bethan because she has lived a full life when so many others feel Primodos caused severely disabling conditions.

“These parents just want reassurance their children will be cared for after they are gone,” she said.

Marie Lyon

Marie LyonMarie Lyon is chairwoman of the association for children damaged by oral hormone pregnancy tests, and her daughter Sarah was born in 1970s with the lower part of her arm missing.

A key goal for her is an acknowledgement that the women were not to blame.

“That’s something we all feel,” she said. “For somebody to say you didn’t do anything wrong – you didn’t eat the wrong food or the wrong drink.

“Secondly a lot of our families are still caring for their children and have never had any help at all. Women have never had the opportunity to work because of caring for the children.

“The prime thing is care for the children.”

Mrs May said: “Although I’ve stood up in the House of Commons and said to the government: ‘You need to say to these women – you are not to blame’ it is so important that they have that sense of guilt lifted from them.

“Because they took something that their doctor gave to them. They had every expectation that they could trust their doctors.

“There are those who are still suffering and the women who still sadly feel that sense of guilt – although no guilt lies with them.”