‘I may have to sofa surf with my six children’

BBC

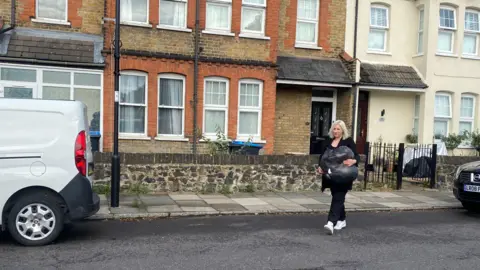

BBCIt’s a warm Wednesday morning in August and mother of six, Carly, is trying to take off her front door to remove the fridge from her home.

Along with her 14-year-old son, she has an hour to frantically move furniture to a van before bailiffs arrive and lock them out of their house for good.

Carly says she has nowhere to go, and does not know where she and her six children, aged between seven months and 16, will sleep tonight.

“I might have to sofa surf,” she says.

Carly has lived in this privately rented, four-bedroom house, in Enfield, north London, since 2018. She was paying £1,900 per month.

Last year, the landlord said he wanted to increase her rent by £100 – an amount she could not afford.

In November 2023, a court issued a possession order but Carly says Enfield Council advised her to stay put until she received further notice from the landlord. She was give two weeks’ notice of eviction.

The impact has been extremely distressing for her and her children.

“The stress alone is unimaginable, I wouldn’t put this on anyone,” she said.

“It’s been a nightmare.”

Rising rents

Carly is one of an increasing number of Londoners facing homelessness after a private tenancy ends.

Currently, a tenant can be evicted with a Section 21 no-fault eviction notice after a fixed term tenancy ends if there is a written contract or during a tenancy with no fixed end date.

Tracks have been made to change this. The previous government promised to abolish no-fault evictions but the Renters Reform Bill failed to become law before the general election.

Now Labour is in government, it has promised to prioritise the issue of homelessness.

Rents have been rising in the UK, but in London in recent years, a demand for properties has outweighed supply and, according to Rightmove, the average monthly rent in May was £2,652, a record high.

In the first three months of 2024, there were 4,600 households claiming homelessness support from their local council following the end of private rental tenancy, a 12% increase on the same period in 2023, campaign group Renters Reform Coalition (RRC) said after analysing government data.

Without a home or anywhere to settle, Carly and her children are preparing to spend the day in the local council offices to apply for emergency housing.

Generally, councils can only help people with accommodation once they are actually homeless.

For Carly, that means she’s had to put all of her things in storage – another extra cost she cannot afford having had to borrow money to pay for it – and faces a long wait with her children.

“You wouldn’t want this for anyone, it’s scary for the children,” she said.

Sarmad Dar, who has run the removal company that has taken Carly’s things to storage for ten years, says the number of evictions he goes to has increased, particularly since the pandemic.

He says he now estimates eviction removals make up about half of his workload.

“These days there’s too many evictions,” he said.

“I believe that the reason is the rent prices are ridiculously high”.

‘Affordable homebuilding’

Deputy prime minister and housing secretary, Angela Rayner, said: “Work is already under way to stop people from becoming homeless in the first place.

“This includes delivering the biggest increase in social and affordable homebuilding in a generation, abolishing Section 21 no-fault evictions and a multi-million pound package to provide homes for families most at risk of homelessness.”

In response, RRC said: “We need to see renters’ rights soon, but the government need to get it right rather than rushing it through.”

Carly’s landlord and estate agents acting on behalf of her landlord declined to comment, but Enfield Council said that Carly and her family were allocated rooms within the day, and assigned a case worker.

Listen to the best of BBC Radio London on Sounds and follow BBC London on Facebook, X and Instagram. Send your story ideas to hello.bbclondon@bbc.co.uk