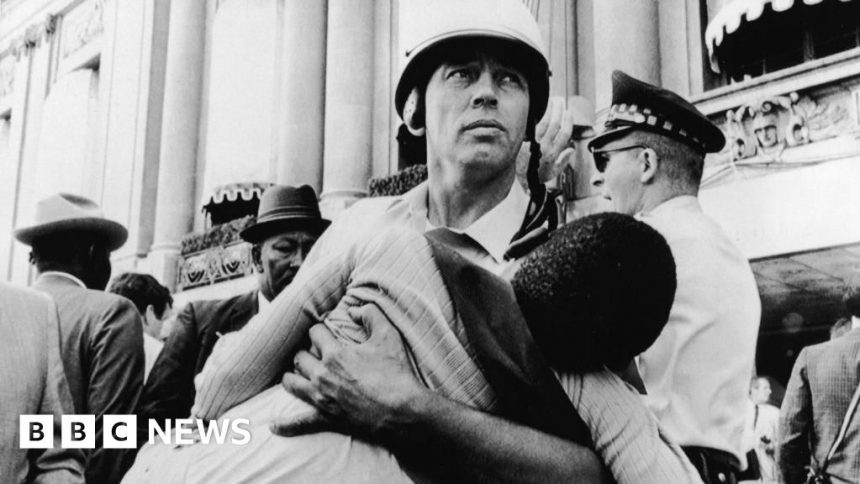

Will the Democratic Convention be a repeat of Chicago 1968?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhen 21-year-old Indiana University philosophy student Craig Sautter drove to Chicago for the 1968 Democratic National Convention, he had an “inkling” that he would be in for a “wild day”.

There had been a series of riots after the back-to-back assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr and presidential hopeful Robert F. Kennedy just months before, and he could tell that simmering tensions were ready to boil over when thousands of protesters, police, politicians and delegates gathered in Chicago in August 1968 to pick who would be the next Democratic candidate for president.

Yet the young anti-Vietnam War activist was still shocked by what he saw: National Guardsmen with bayonets, protesters ripped from cars or beaten with police batons, and thick clouds of tear gas wafting through crowds of thousands.

“We were mostly middle-class kids, or business people who were there in suits, protesting the war,” Mr Sautter recalled. “We never thought that the police would attack an unarmed group of people who were just singing and shouting… we were in disbelief.”

Ultimately, more than 600 protesters were arrested and over 100 treated for injuries, alongside 119 police officers.

Scenes of the violent clashes in the streets and parks of Chicago soon flashed on TV screens across the country, and the world, leaving an unforgettable image of America in chaos.

“People were chanting that the whole world was watching,” added Mr Sautter, now a professor at Chicago’s DePaul University who researches presidential conventions.

The return of the DNC to Chicago in 2024 has led many to look back at 1968 and draw parallels. Like back then, there will be anti-war protests – this time against the Biden administration’s support for Israel during the war in Gaza.

And like back then, there has been a surprising change of guard amongst Democratic leadership. In 1968, President Lyndon Johnson announced he would not seek re-election months before the convention, while this time, President Biden pulled out of the race with merely weeks to go.

But experts and veterans of the 1960s protest movement believe the differences far outweigh the similarities.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSome of those involved in planning the anti-Gaza war protests at the upcoming DNC say they draw inspiration from the work of the earlier activists nearly 60 years ago.

“This is the Vietnam War of our era,” Hatem Abudayyah, a spokesman for the Coalition to March on the DNC, told the BBC. “The attacks on our movement, our students and our organisations are similar to the attacks on the movement that was trying to stop 1968… I absolutely see those parallels.”

The coalition includes over 200 organisations involved in the protests, and its spokespeople have said that “tens of thousands” of participants are expected.

The size of the protests has prompted Chicago’s police department to warn that it won’t tolerate “violent actors” or incidents of vandalism or criminality.

Yet Mr Abudayyah does not think that violence is an inevitable outcome, saying that there has been “no evidence of any violence” over 10 months of protests organised by the coalition or its member groups since the conflict in the Middle East began.

Others have pushed back on the comparisons, saying that any similarities are few and far between.

“Other than the fact that they’re in Chicago, there are none,” long-time Democratic National Committee member and DNC delegate Elaine Kamarck told the BBC. “This is not even close.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOne of the key differences, according to Ms Kamarck, was the “very, very thuggish tactics” of the Chicago police, who a federally-mandated commission later accused of a “police riot” at the DNC.

Just months before, then-Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley had also issued “shoot to kill” orders in the wake of riots after Martin Luther King’s death.

“All hell was breaking loose,” said Ms Kamarck, who was 18 at the time. “There’s no such thing going on now.”

Ms Kamarck’s assessment was echoed by Marsha Barrett, a professor of US political history at the University of Illinois-Urbana Champaign.

“Daley had very strong control over police, and an antagonistic relationship with protesters,” she said. “The city had set up a situation where there was likely to be a major conflict.”

“We don’t have that now,” she added.

Chicago police have been in regular touch with DNC protest groups and have vowed to protect their rights to free speech, provided that the protests remain lawful.

“The understanding of police activity at that time was that the would use whatever force was needed to overcome resistance,” said Mr Sautter.

“Now the police are better trained,” he added. “They’re not going to provoke anything unless some kind of violence breaks out.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAmong those who witnessed the violence first-hand was Abe Peck, then editor of the Chicago Seed, an underground newspaper linked to the Youth International Movement, or Yippies, that planned events around the 1968 convention.

“We were in our office, which was in a dry cleaner’s, and all of a sudden our window fragmented,” remembers Mr Peck, who was later credited with creating the “whole world is watching” chant. “Two shots were fired through it. Fortunately nobody was hit.”

When they ran outside to investigate, Mr Peck saw only one vehicle: a Chicago police cruiser.

The incident was one of several which marked his experiences of the DNC, which also included the police “stomping out” religious ministers tied to the counterculture movement.

That violence, Mr Peck told the BBC, stands in stark contrast to today.

Social media and the immediate spread of news could create a public relations disaster if police were seen to be too aggressive.

“Back then, there was a real delay in getting news out. Now, it’s essentially instantaneous,” Mr Peck said. “That’s a big difference.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDon Rose, who in 1968 was a spokesman for the National Mobilization Committee to End the War, one of the main protest groups, told the BBC that an even more significant difference was the Vietnam War itself.

That war, unlike the Gaza war, saw tens of thousands of Americans drafted, many of whom were killed or wounded overseas.

“The country was far more divided on the Vietnam War at that time. The protests expanded greatly because of the draft,” said Mr Rose, now 93.

“We were protesting at a convention that would nominate someone who could end the war with the stroke of a pen,” he added.

The Democratic Party at the time was also deeply divided over the war, and when delegates arrived at the DNC of 1968, they had no idea who would be leaving with the nomination.

When then-vice president Hubert Humphrey was finally chosen as nominee over anti-war Senator Eugene McCarthy, some in the audience even shouted “No!”.

“The convention was totally divided, and at war with itself,” explained Mr Stautter. “For [Kamala] Harris and Walz, it’s totally unified.”

Mr Peck, for his part, said that more recent versions of the DNC can no longer be called “nominating conventions”.

“These are just confirmation conventions,” he said. “They confirm what the people in states did at the primary levels. That’s really different.”

Ultimately, Hubert Humphrey went on to lose the 1968 election to Republican Richard Nixon.

Looking back, Mr Stautter – who will be watching the convention on TV this year – believes that the protests of 1968 had an impact on the US that could never be replicated in 2024.

“People who watched were totally radicalised by it, and many, many more people became involved in trying to stop the war,” he said.

“A whole generation, whether they were there or not, were marked by it.”